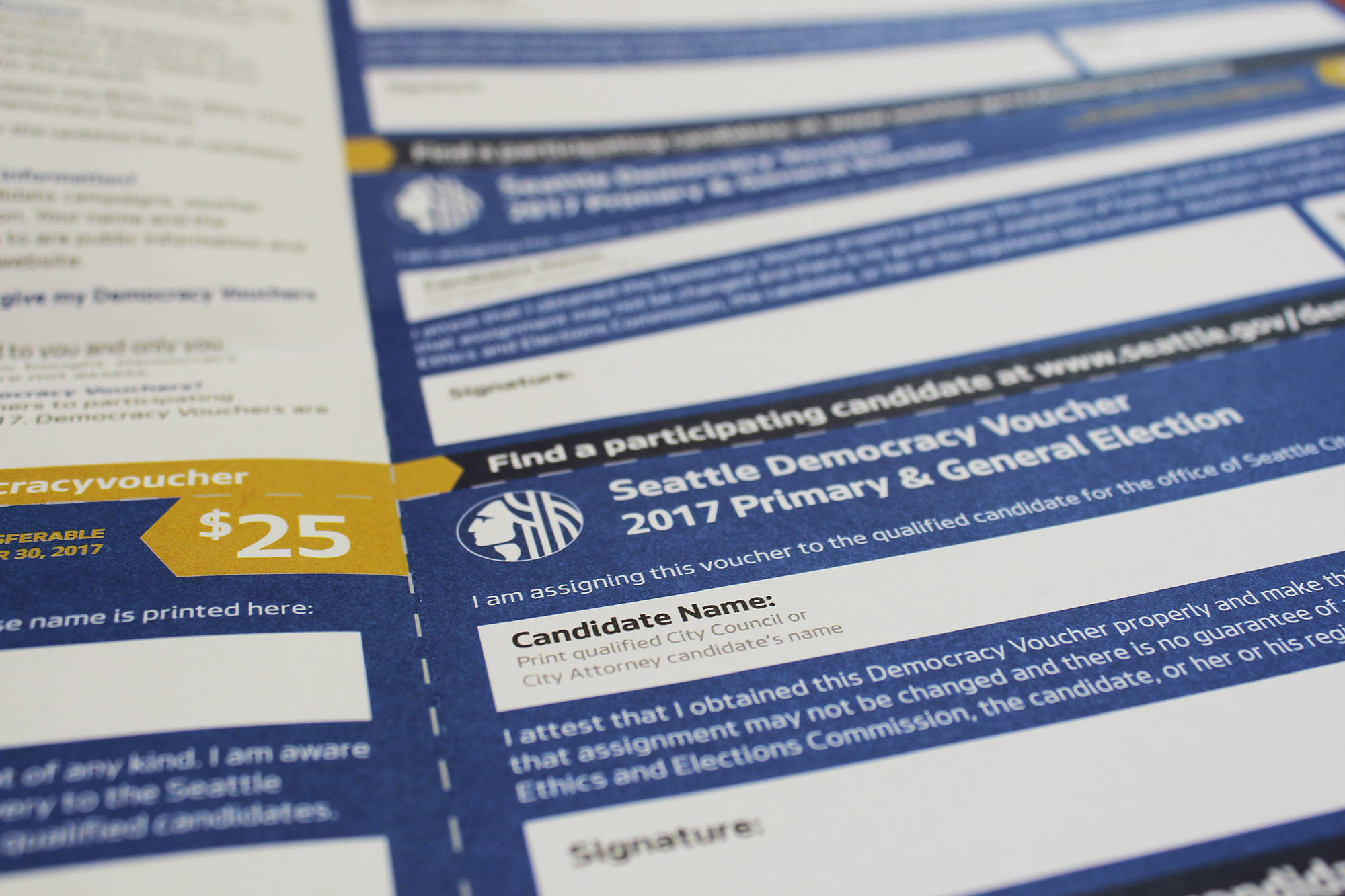

This week featured the first general election in which Seattle residents and candidates were able to use the city’s new taxpayer-financing system for political campaigns. The so-called “democracy vouchers” program levied a new property tax in order to provide every voter in the city with four $25 vouchers that they could in turn give to politicians.

The program has been billed as an “experiment” in campaign finance policy, and some activists rushed to declare it a success before the campaigns even concluded. Although only three local races featured candidates participating in the program (17 out of 26 candidates took part – in two city council races and one city attorney contest), the results still provide a small taste of what to expect from “democracy vouchers” in terms of their power to transform government and politics.

The answer seems to be: not all that much.

Supporters of the program claimed victory on the basis of donor participation. They point to any increase in donors or change in the makeup of those who give as evidence of empowering the previously-underrepresented – almost akin to transforming the electorate itself. Campaign contributions are certainly one important way of participating in democracy, but the end goal of such activities is ultimately to impact the makeup of government through elections, and thus influence the substance of policy. Citizens donate to candidates to provide them with resources necessary to run their campaigns and to express symbolic support for their agendas. A well-funded campaign is a sign of a politician’s organizational skill and level of support among the broader public – at least in a voluntary campaign finance system.

It’s not surprising that people are more likely to spend free money. However, changing the donor makeup in a jurisdiction is not an accomplishment in and of itself. That’s why, when examining tax-financing programs, it’s smarter to examine tangible electoral outcomes.

One outcome to look at is the influence of “big money” in elections. Two years ago, when Seattle first passed its “democracy vouchers” program, the Brennan Center for Justice, which supports more government regulation of political speech, touted the development as a city “leading [the] fight against big money.” This proved to be untrue even before the general election: hundreds of thousands of dollars in spending from business and labor groups had been pouring in as of this summer. And in each of the races, the winner ended up outraising his or her opponent – in one case (City Council Position 9) receiving almost twice as many contributions. While higher fundraising certainly indicates the level of support for a campaign, in Seattle’s case, the existence of “democracy vouchers” aren’t translating to a reduction in so-called “big money.” This year even saw attempts to defraud the voucher program of taxpayer money – an all-too-common occurrence in such programs. None of this bodes well for the power of “democracy vouchers” to reduce the role of money in politics (or to reduce political corruption).

Another place to scrutinize is electoral competition. Tax-financing programs in general are purported to create more “contested and competitive” elections (this does not seem to actually happen), and Seattle’s system in particular was designed to “rais[e] the voices of everyday people.” In this year’s elections, however, both incumbents who sought re-election won their campaigns. In the third case, where the incumbent did not run (for Seattle’s at-large City Council seat), a well-funded labor leader trounced a well-known affordable-housing activist – not exactly an underdog story.

A final category to examine is diversity, which is one of the most touted potential benefits of the program. Since only one non-incumbent won an election this year, there obviously wasn’t a big change in the makeup of Seattle’s government in terms of gender or racial diversity. Indeed, only a third of Seattle’s city council members were white men to begin with. Since both the current and future holder of Seattle’s at-large City Council seat are minority women, the election results don’t change that fact. This outcome is in line with the failure of tax-financing systems to improve gender or occupational diversity elsewhere.

In these three areas – decreasing the role of “big money,” increasing the voices of everyday people, and increasing diversity – the results of Seattle’s experiment are, thus far, inconclusive at best and negative at worst. To be sure, this is just one small sample of what politics and government look like under a tax-financed political system. But based on past experiences with tax-financing programs, we shouldn’t be surprised to see politics as usual, except with the added injustice of taxpayer dollars subsidizing politicians.