Data from the 2016 election continues to undermine a key prediction made by critics of Citizens United in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s famous 2010 ruling. Once again, super PACs are being funded overwhelmingly by citizens, not corporations. As reported by The Wall Street Journal, “A study by the Conference Board’s Committee for Economic Development found that individuals made about 80% of all super PAC contributions in the 19 months through July 31. Companies contributed just 8% in the period and unions a mere 1.9%, according to the report slated for release Wednesday.”

Longtime readers will recall that critics of Citizens United warned that corporations would jump at the chance to spend large amounts urging voters to support candidates whose policies favor big business. (Ironically, many media outlets – themselves corporations – took up this line of thinking as well.) After all, individuals already had the ability to spend unlimited amounts independently advocating for or against candidates dating back to 1976’s Buckley v. Valeo decision. Citizens United paved the way for unions and incorporated groups to get in the independent expenditure game, and speech regulation advocates feared they would – in force.

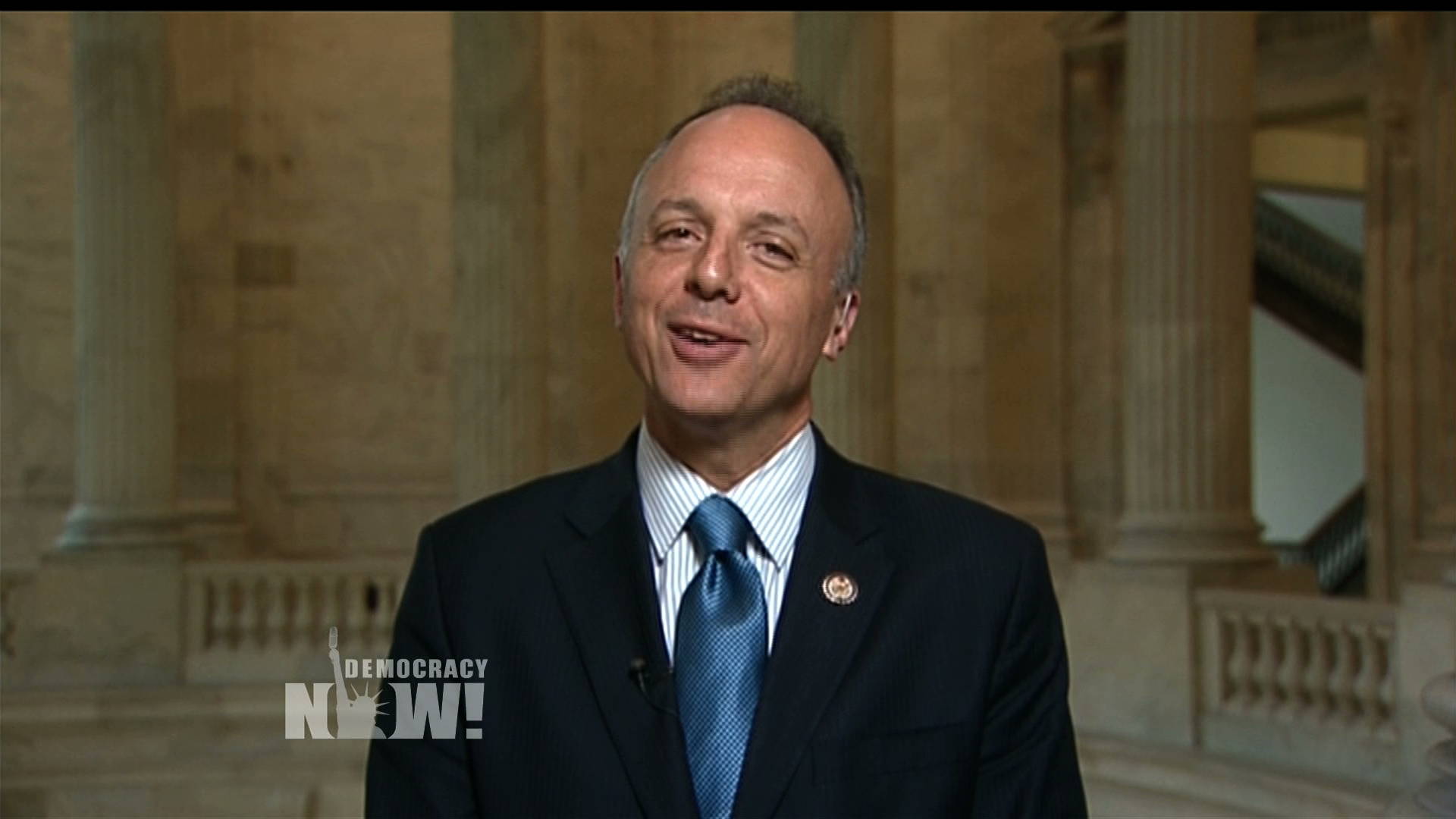

The New York Times Editorial Board quickly declared that the ruling had “paved the way for corporations to use their vast treasuries to overwhelm elections and intimidate elected officials into doing their bidding.” In a statement to the press, President Obama called it, “a major victory for big oil, Wall Street banks, health insurance companies and the other powerful interests that marshal their power every day in Washington to drown out the voices of everyday Americans.” Congressman Alan Grayson went further, deeming Citizens United the worst Supreme Court ruling since Dred Scott and claiming it meant “that only huge corporations have any constitutional rights.”

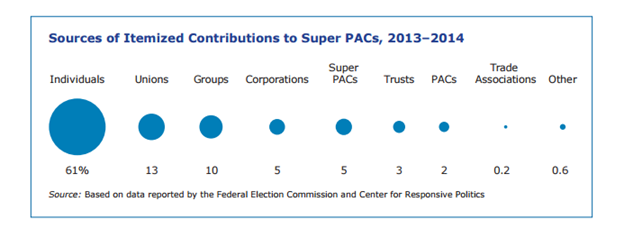

Contrary to these dire predictions, however, super PACs – created through the subsequent D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals decision in SpeechNow.org v. FEC – have not been vessels for corporate influence. Rather, super PACs have served primarily to amplify the speech of citizens with shared political views. In addition to providing 80% of super PAC contributions in 2016, individuals also dominated super PAC giving in 2014, according to CED. 61% of super PAC contributions came from individuals that cycle, compared to 13% from unions and 5% from corporations.

Notably, these findings – which are consistent with previous analyses of super PAC funding – have not lessened speech regulation advocates’ fervor for abolishing super PACs or overturning Citizens United. Their argument has instead shifted, and now, rather than claiming that super PACs will allow corporations to drown out candidates and parties, proponents of restricting independent expenditures claim they allow candidates and parties to circumvent contribution limits. Their concern is no longer that “outsiders” will crash the system, but that insiders are gaining advantage. It seems that no matter what super PACs do, they’re villains to some.

CCP has long pointed out that regardless of whose political agenda temporarily benefits or suffers from allowing more speech about elections, voters gain knowledge and interest in elections from hearing about candidates and issues. Super PACs facilitate that speech, including from corporations – who often have valuable things to say about the effects of new laws or regulations on jobs and businesses. (And the public supports that speech, by the way.) But so far, super PACs have not been mouthpieces for big business, as critics of Citizens United feared. Rather, they’ve spoken with the collective voice of their donors, most of whom are individual citizens.

2016 has been a deflating election cycle for those accustomed to hyping money’s role in politics. From a reduction in so-called “dark money” to lagging spending in federal elections to CED’s finding that super PACs are 80% funded by individuals, empirical evidence consistently undercuts the hysteria stoked by activist groups and repeated uncritically in the media. Maybe this year will mark a turning point in how experts view campaign finance regulations. Or maybe evidence will be swept aside in favor of narrative once again.