Congressman Ken Buck (R-CO) is a founding member of the Freedom Caucus and the latest conservative to come out with a book criticizing the sausage-making in Washington, D.C. In 2013, it was Peter Schweizer with Extortion: How Politicians Extract Your Money, Buy Votes, and Line Their Own Pockets. In 2015, it was Jay Cost’s A Republic No More: Big Government and the Rise of American Political Corruption. 2017 now has its corruption-from-the-right tell-all in Drain the Swamp: How Washington Corruption is Worse than You Think. (What is it with conservative authors and subtitles?)

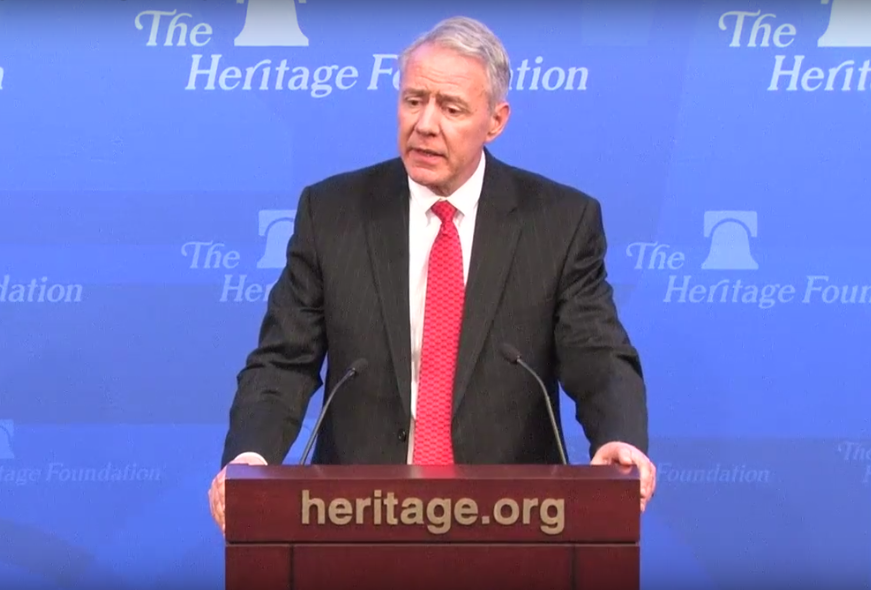

Buck spoke about his new book at a Heritage Foundation event Thursday. As with Schweizer and Cost, Buck’s Congress-bashing – a national pastime in its own right – is far more compelling than his ideas for solutions. Progressive advocates of increased campaign finance regulation tend to seize on these books as evidence that conservatives also want speech-restricting policies. But while the left and right can usually agree that Congress is bad, they almost never agree on why or how to fix it.

Case in point: Buck’s proposed solutions are ideas that most self-styled reform organizations actively oppose. Specifically, Buck favors term limits on members of Congress, and supports an Article V Convention of the States to amend the U.S. Constitution. Many speech regulation advocates on the left believe that term limits increase the power of lobbyists by depriving the legislature of its most experienced and institutionally knowledgeable members. Many of those same individuals support constitutional amendments to overturn Citizens United or Buckley v. Valeo, but not through an Article V convention, which they fear would do more harm than good to their cause.

If there is little agreement about how to solve the problem of corruption in D.C., it is perhaps because the term “corruption” can mean different things to different people in different contexts. In campaign finance jurisprudence, corruption has a narrow meaning. It refers to the exchange of favors for campaign contributions. Many progressives instead see “corruption” more broadly as a political system in which wealthy people have more avenues to attempt to influence the government than others. Rep. Buck’s discussion of corruption in D.C. suggests a third definition of the term.

Rather than talk about exchanges of money for favors, or perceived inequalities in the political system, Buck focuses on the actions of party leadership to carrot-and-stick their members into compliance. He says this serves “special interests,” but the real pressure faced by rank-and-file members of Congress isn’t from donors, it’s from party leaders. That might be a problem, but is it corruption? And more importantly, is it a problem we can prevent or reduce with new restrictions on groups engaged in political advocacy and speech?

Buck’s remarks give little reason to think that’s the case. Notably, he thanked “groups in Colorado,” whose support allows him to break with the establishment and so-called “special interests.” Those groups would surely be considered special interests by others. Buck also thanked “great organizations like the Heritage Foundation” – nonprofit advocacy groups that most “reformers” want to hamper with forced donor disclosure and reporting requirements similar to those required for PACs.

As we often find in politics, the difference between a “special interest” attempting to “buy” policy outcomes and a group of citizens supporting causes they believe in depends on whether or not you like the group and policy in question. Everyone is free to complain about the parts of politics they don’t like, and members of Congress understandably aren’t big fans of asking supporters for donations, or taking heat for breaking with their party on a vote. But advocates of greater regulation of political speech shouldn’t misread these complaints from some conservatives as calling for expansive new speech rules. More accurately, they are criticizing the culture of D.C. and government in general.

Changing that culture and “draining the swamp” isn’t done by writing new regulations. It’s done by creating room for outsiders to challenge the status quo with new leadership and new ideas. To that end, campaign finance deregulation, rather than new restrictions on speech, is just what the doctor ordered.