On Election Day last Tuesday, voters in Broomfield, Colorado decisively approved Question 301; a ballot initiative that grants the city greater authority to regulate the oil and gas industry operating within its borders. Question 301 is part of a much larger, ongoing debate over the regulation of drilling for fossil fuels in Broomfield and elsewhere in Colorado. As such, it is not surprising that questions over the regulatory authority of municipal governments in this area popped up in several other local elections across the Centennial State last week.

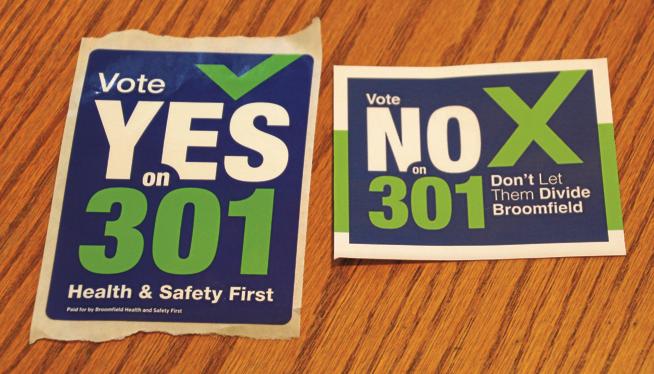

Question 301 was placed on the ballot by Broomfield Health and Safety First, a group of residents with shared concerns about the impact of industrial oil and gas fracking sites in their community. The initiative was pitched to voters as providing their City Council with another tool to ensure that residents’ health and safety were given first priority in oil and gas contracts. On the other side, the “Vote No on 301” campaign argued that this ballot initiative actually constituted a step backward for the city. The “No” campaign contended that passing the ballot question would undermine the current steps being taken to collaborate with members of the oil and gas industry to draft a new city charter, intended to help guide future negotiations with these companies.

While only a local ballot initiative, both campaigns garnered a good deal of support and attention throughout the race. Broomfield Health and Safety First, the group in favor of passing the initiative, raised around $46,000 to help spread their message, with $35,000 of that total coming from the Sierra Club and the rest originating from small-dollar contributions from individuals. Those who opposed Question 301 were able to raise a significantly higher sum – nearly $350,000 – largely from groups such as the Colorado Petroleum Council and Vital for Colorado, a coalition that seeks to limit the state’s regulatory oversight of the energy industry.

Despite what those who favor greater campaign finance regulation would have you believe, the Broomfield question serves as another example of “big money” failing to buy an election. The “Vote No on 301” campaign outraised their competitors by more than 7:1, and yet, at the end of the day, they lost because their message failed to adequately resonate with Broomfield’s residents. The results of Tuesday’s election reflect a conscious choice made by voters that the outcomes achieved by Question 301 would be more favorable for themselves and their community.

On the other hand, while it was Broomfield’s voters who made the final decision, spending by national nonprofit groups on both sides of the ballot initiative still played a crucial role. Contributions from both sides allowed each issue campaign to run advertisements, purchase bumper stickers and yard signs, and cover all of the many costs associated with running a campaign. Contributions from the Sierra Club, the Colorado Petroleum Council, and Vital for Colorado empowered both campaigns to disseminate information about their platforms and reach more residents. All of this spending allowed voters to make a more informed decision prior to voting.

Even so, individuals on both sides were quick to deride their opponents as beholden to either the oil and gas industry or ‘extremist’ environmental groups. However, given that the ballot initiative was concerned with fracking and its impact on the environment – both of which are fairly hot-button topics – involvement by state and national groups focused on energy production, the environment, and local governance is unsurprising.

With respect to Broomfield’s ballot question, as in most other local, state, or federal elections, people disagree about the most acceptable or effective way to finance campaigns. On one side, there is the notion that grassroots campaigns funded exclusively by small dollar contributions are the most desirable, because they allow voters to be more engaged in the political process, while limiting the involvement of wealthy individuals and groups. (Recognizing this, many politicians are increasingly devoting resources to small-dollar fundraising, and have achieved success in getting more Americans involved in politics.) On the flip side, there are many who believe that enabling groups of individuals with shared beliefs to speak on issues and contribute to campaigns without limit is a better method. This is because the more funding a candidate or group is able to receive, the better it’s able to communicate its message. Contributions to both sides of the Question 301 debate from groups such as the Sierra Club or Vital for Colorado help small groups of concerned citizens reach more voters.

However, the view that campaigns must be financed one way or the other is shortsighted. Both individuals and groups, small contributions and large, are important – if not essential – components of a successful campaign. There is no need for the roles of individual voters and groups in elections to be mutually exclusive, because together they help foster a much more educated and engaged civil society.