Earlier this month, Jonathan Rauch – a Senior Fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution – and Raymond J. La Raja – an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst – co-authored a report on the role of political parties and independent, non-party groups in selecting and cultivating political candidates. Their report examines the growing influence of independent organizations and the relative decline of formal parties as “gatekeepers” in the political process. Although the report does not dive into great detail on campaign finance law, it still has important implications for that field.

Rauch and La Raja weigh the potential benefits and downsides of this decades-long trend. On one hand, the authors imply that independent groups have helped make U.S. politics more democratic. They recount a story from an eventual congressman who sought to volunteer for a presidential campaign in 1948, only to be turned away by a Democratic Party boss in Chicago: “Who sent you?… ‘Nobody?’ We don’t want nobody that nobody sent.” This sort of casual elitism overtly excluded people from the political process and has declined over time. As those barriers have fallen, there has been a corresponding rise in people running for office. Part of this shift is due to independent groups increasingly seeking to shape the system by recruiting their own favored candidates. As the authors note, “By the time the primary ballot is printed, it’s often too late.”

On the other hand, Rauch and La Raja also suggest that independent groups make politics more dysfunctional. Their tendency to focus on “primarying” incumbents and establishment-backed candidates, the authors argue, serves to move each party further to the left or right, thus making political discourse more toxic and extreme. This, in turn, causes fewer moderates to run for office, since a greater premium is placed on ideological purity than resume and ability to compromise.

The conflict this creates between independent groups and parties has become formulaic: “viable” candidates suffer defeat, which leads either to losing an erstwhile winnable election, or increased difficulty in governing. Although some independent groups do put a premium on “governing” ability (the authors mention the U.S. Chamber of Commerce as one such group), overall, there is less emphasis on “vetting” candidates for moderation. Some activists have even dismissed “viability” as a “construct of political elites.”

Regardless of whether these trade-offs are a net benefit or detriment to American politics overall, it is a trend that is certainly going to continue. Over the past few decades, contributions and expenditures by individuals and “outside groups” have surpassed traditional PAC contributions to candidates. (This does not include PAC spending, or the fact that independent groups generally spend less than candidates and parties.) Look, for example, at the makeup of progressive political donations during the Trump presidency: while the DNC has struggled to keep pace with Republican fundraising, independent groups on the left have been raking in cash and recruiting many more candidates for office. The formal party structure has stalled, but politics continues apace.

The authors see independent groups as a double-edged sword for parties: although they can create headaches, they can also help pursue shared political goals. A “natural division of labor” has emerged, whereby parties focus on winning general elections in swing states and districts, while non-party groups focus on primaries and safe districts. Even if the party opposes ideological, activist-backed candidates in primaries, it will typically help pull them across the finish line in the general election (unless they are particularly toxic or scandal-stained).

In the end, Rauch and La Raja offer two broad recommendations for restoring party influence. First, they argue parties should reassert control over candidate selection through stricter rules for primary ballot access, or through norms and rituals like pre-primary straw polls. Second, they suggest that parties generally strengthen themselves as institutions in terms of resources. This is where money comes more into play. The authors suggest removing “obsolete regulations which selectively disadvantage state parties,” or perhaps making party donations tax-deductible.

Besides these suggestions, the authors do not go into much detail on the role of money in the health of parties. This makes some sense, since they correctly point out that “who sends candidates is much more important than who sends money.” After all, voters are ultimately the ones who must select their representatives, not donors. It may actually be that the rise in political extremism comes from voters themselves, rather than select donors.

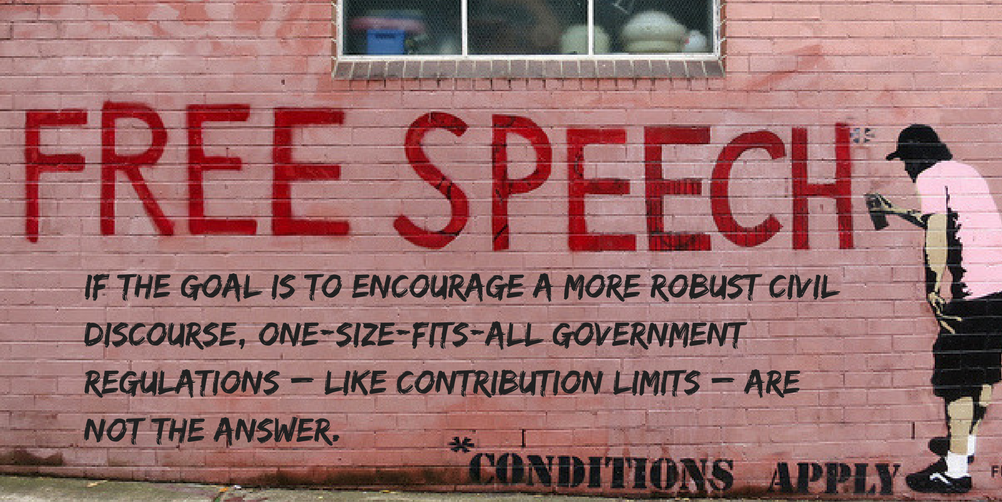

In the past, the authors have delved more deeply into the role of campaign finance regulations in the weakening of political parties. There is a collection of specific obstacles that make giving to parties less attractive than supporting super PACs or advocacy groups: contribution limits, reporting requirements, coordination restrictions, etc. Indeed, such government interventions in campaign finance can make things worse: the former mayor of Tempe, Arizona, has been quoted as saying his state’s tax-financing system has made political extremism worse, not better.

For those who want political parties to maintain their stabilizing influence in politics, the best solution is to stop hobbling them with confusing regulations. For those who welcome the democratizing influence of independent advocacy groups, they may thank the courts for appropriately striking down restrictions on the giving and spending of money on First Amendment grounds. Both outcomes require the same formula: allow more speech from more people, with fewer government restrictions.