In politics, it’s easy for narratives to take hold before the facts have a chance to catch up. Political speech issues are no different. In the heat of a campaign, developments in political spending are often reported as if they are the most important factors in determining electoral outcomes, but does this hold true when we look back at the facts? The Campaign Finance Institute’s (CFI) recent report, “Guide to Money in Federal Elections: 2016 in Historical Context,” may help shed more light on how political speech did and didn’t shape races in that election cycle.

Among its many findings, there are several that stick out for bucking the conventional wisdom of those who seek more regulation of political speech. The findings I specifically highlight in this post point to the same conclusion we’ve reached before: money is just not as impactful as people think it is.

That’s not to say money’s not important. The authors of the report, Michael J. Malbin and Brendan Glavin, point out that campaign fundraising is an important metric in many senses. Not only does it indicate the degree to which people support a candidate or cause, but it provides recipients with the resources to reach out to even more voters through ads or campaign activities. Restricting the ability to give and spend money impedes the ability to exercise free speech in any meaningful sense.

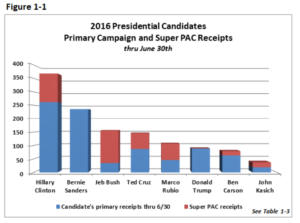

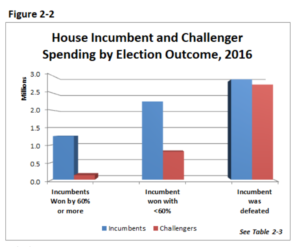

But one should be cautious about overstating money’s impact on elections. 2016 showed that money doesn’t “buy” election outcomes – after all, Donald Trump was outraised by Hillary Clinton (see Figure 1-1) at all stages of the campaign, and successful congressional challengers tended to spend less than the incumbents they defeated (see Figure 2-2). Even the much-vaunted “invisible primary” – whereby the presidential primary field is purportedly shaped by fundraising in the year before primary elections occur – is not straightforward. Barack Obama and John McCain in 2007, and Donald Trump in 2015 were not the fundraising leaders in their respective parties, but still managed to capture the nomination.

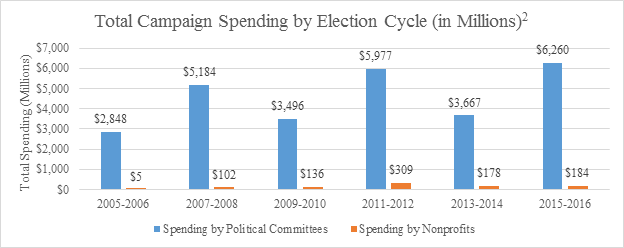

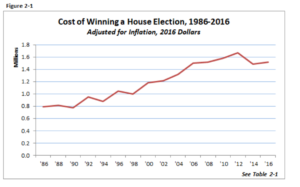

Even the magnitude of money in politics isn’t quite what people think, according to CFI. To be sure, independent expenditures (that is, non-candidate, party, or PAC spending) have increased over the last few cycles, in part thanks to the greater political speech freedoms afforded to advocacy groups by the Supreme Court. (This is not always the case – High Court decisions like 2014’s McCutcheon v. FEC have not led to subsequent explosions in coordinated spending, as some pundits predicted.) But since 2006, candidate spending in congressional races has more-or-less remained flat recently when accounting for inflation – after steadily rising in the decades prior. The “cost” of winning a House election has similarly stagnated over the past several cycles (see Figure 2-1).

Moreover, government policies intended to limit the amount of political spending are ineffective at best and harmful at worst. The stagnation in the cost of winning a U.S. House election occurred despite deregulatory trends in campaign finance. The biggest factor that determines the amount of political spending is simply how much is needed to effectively communicate with the public. That is, in turn, determined by a variety of factors like the cost of traditional media or the proliferation of lower-cost internet-based strategies – which certain candidates may be better at utilizing than others. Ultimately, it’s up to candidates to decide how much they need to spend, not the government. Indeed, the CFI report notes how tax-financing of presidential campaigns – a program meant to incentivize candidates to accept spending limits – gradually deteriorated over time, as the actual cost of campaigning surpassed the ceiling set by the government.

CFI’s report is an important step forward in better understanding the 2016 elections – and by doing so, sheds more light onto the nature of political campaigns and the role that political spending plays in our electoral process.

Please note: All graphs are reproduced courtesy of the Campaign Finance Institute’s “Guide to Money in Federal Elections: 2016 in Historical Context” report.