We live in an increasingly connected world. This trend has only intensified in an era of internet and video communication brought forth by COVID-19. Social media, in particular, has been an incredible driving force for building coalitions and organizing people that share common interests. This has dramatically changed and improved the ability of Americans to associate with one another.

Technology, however, is a double-edged sword, and the ability to more openly communicate with others has also exposed large amounts of our private lives to scrutiny. Social media allows us to share more of ourselves with others but can open a window into aspects of our lives that we may not want to be public. This loss of privacy comes at a serious cost, and there is a danger of individuals who want to preserve their privacy self-silencing and refraining from exercising their First Amendment rights.

If we want more speech and association in our society (and we should), then we need to focus on bringing down the costs for individuals who wish to speak out. Protecting privacy while allowing individuals to speak is an important way we can lower the cost of speech and promote more of it.

Protecting privacy is not just good policy, it is also constitutionally mandated. The First Amendment protects the freedom to associate privately with others in support of causes. In the landmark 1958 Supreme Court case, NAACP v. Alabama, the Court ruled unanimously that Alabama’s attempt to force the NAACP to turn over its membership list was unconstitutional and that individuals have the right to privately associate with like-minded citizens. The Court was particularly concerned about members of the NAACP being harassed or retaliated against for exercising their constitutional rights. The Court also ruled that First Amendment freedoms need “breathing space to survive” – space created by strong protections for associational privacy.

Technology and government have steadily encroached on this “breathing space” in many ways. In the 2018 Supreme Court case, Carpenter v. United States, the government argued it had the right to seize cell phone location records without a warrant. The access the government sought was breathtaking. Most Americans are inseparable from their cell phones. Access to cell phone location records would grant law enforcement a window into everywhere you go, giving them powerful clues about what you’re doing and who you’re speaking to. In effect, the government was asking to surveil the exact movements of any American, provided of course they did not leave their cell phone at home.

The Institute for Free Speech filed a joint amicus brief with an array of groups arguing that such easy access to cell phone records would threaten the First Amendment by undermining the ability for individuals to privately associate with one another. The Supreme Court recognized the danger to associational freedom in a decision that prohibited the government from accessing these sensitive records without a warrant.

Concerns about tracking Americans have resurfaced recently during Black Lives Matter protests across the country. Civil liberties advocates have voiced concern that police are “geofencing,” a technique enabling law enforcement to monitor social media posts in a specific area. For example, a police officer could identify the location of a BLM protest and geofence social media posts coming out of the protest area. Voila! The police officer now has the social media accounts of individuals at the protest – often leading them straight to the protesters’ identities.

Police officers have also kept a watchful eye on protesters by creating fake social media accounts to contact protest organizers. A Memphis police sergeant admitted to creating a fake social media account using the name “Bob Smith” to surveil lawful protesters. More than 150 law enforcement agencies have monitored people this way. There is seemingly little oversight and standards for these practices: A 2014 LexisNexis survey found that 70% of officers self-taught online surveillance operations, and only 48% of departments had formal processes for operating online investigations. The same survey also discovered that 40% of law enforcement officers engaged in social media monitoring of large events, and 80% of officers agreed that creating a fake social media account for law enforcement activity is ethical.

NAACP v. Alabama and the line of cases that followed should have taught us the danger of letting government attempt to pierce group association. The lack of training and oversight for these police actions suggests a worrying lack of concern for Americans’ First Amendment rights. Other government tracking of protesters has been more overt. St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson published the names of individual BLM protesters. In New York City, police may have violated orders by questioning detained protesters about their political beliefs and associations. On June 1, it was reported that the FBI used its most advanced spy plane to monitor Black Lives Matter protesters in D.C. The government also engaged in aerial surveillance of protests responding to George Floyd’s killing in 15 cities across the country and collected 270 hours of footage, possibly more.

Individuals should have the ability to attend a protest without having their identities exposed. Ayo Omolewa wanted to attend a protest in Washington, D.C., but was worried about his identity being revealed. In order to avoid surveillance, he was constantly on the lookout for cameras and was encouraged to set his phone on airplane mode and not use GPS to avoid being tracked. He also refrained from posting anything on social media while he was at the protest to avoid having his identity captured by geofencing. These practices are concerning examples of the steps people must take in order to avoid surveillance and potential retaliation for their political speech.

When technological surveillance shatters the ability to speak and associate privately, it can drive well-meaning people out of the public square. Although Ayo ultimately attended the protest, it’s likely many others had the same concerns and avoided protesting at all. And other protesters who are less aware of the surveillance risks may not have exercised the caution Ayo did and now find their data and identities in the potential hands of law enforcement.

We should take action to protect the privacy of individuals and safeguard their First Amendment rights. Some proposals are beginning to emerge. For instance, two senators introduced legislation that would ban the use of facial and biometric recognition technologies by federal law enforcement agencies.

While collecting private data about individuals can chill speech, warehousing sensitive information also provides a rich target for hacking and leaks. This issue was vividly demonstrated in Maine, where a police intelligence agency collected large amounts of data monitoring racial justice protests that was leaked and published. Recognizing the danger posed by private information that can be leaked, the Institute for Free Speech urged the IRS to change its reporting rules for nonprofits so that the government would not have to collect and store sensitive private information it doesn’t need. The IRS finalized that reform in May.

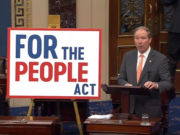

While the IRS has taken a step forward, many politicians want to roll back protections for private association. Both in Congress and in the states, bills have been proposed that would expose supporters of nonprofit groups that speak about government or policy issues. These proposals threaten the ability of civic organizations to contribute their views and expertise to public policy debates and to serve as watchdogs against public corruption.

The Institute for Free Speech tracks threats to privacy and speaks out when constitutional rights are threatened. States like Arizona and Mississippi have made positive strides by adopting legislation that generally prohibits the government from collecting or releasing private information about donors to nonprofits. Other states should follow their lead. Americans have a constitutional right to join and support organizations without having their privacy compromised. People should feel secure engaging in lawful First Amendment activity, including protests, without the government surveilling their every move. People should also feel comfortable donating to an organization without fear of having their contribution, name, and home address released to the public.

Our country was built by associations of people coming together to realize common goals. Increasing the costs of working with others will shut out many from speaking and limit our ability to achieve collective aims. The government should take steps to protect the privacy of individuals because privacy is deeply connected to the core of the First Amendment.