On October 6, 2023, Institute for Free Speech Chairman and Founder Bradley A. Smith and President David Keating were invited to testify before the Kansas Legislature’s Special Committee on Governmental Ethics Reform, Campaign Finance Law to share free speech best practices and make recommendations to protect First Amendment rights in Kansas.

Read a PDF of the full testimony here.

See the presentation PowerPoint here.

Watch the full presentation below:

Statement of Bradley A. Smith

Chairman, Institute for Free Speech

Josiah H. Blackmore II/Shirley M. Nault Professor of Law

Capital University Law School

and

David Keating

President, Institute for Free Speech

before the

2023 Special Committee on Governmental Ethics Reform, Campaign Finance Law

October 6, 2023

Chairperson Proctor, Vice-chairperson Thompson, and members of the Committee, on behalf of the Institute for Free Speech, thank you for inviting us to testify at this meeting.

In August 2022, we published our Free Speech Index of the 50 states. It’s the most comprehensive report ever published on state laws regulating speech about government and public policy. An editorial in The Wall Street Journal told readers, “it’s worth spending a few minutes to read a new report from the Institute for Free Speech. It’s an index of how state laws and regulations treat political committees, grassroots advocacy, independent expenditures, and the like. The results aren’t partisan, and they’re probably not what you expect.”

We regret to say that Kansas earned a disappointing 65% score in this report. Many of the free speech deficiencies in Kansas’s law would be addressed by some minor changes. A key problem is that the current law’s definition of a PAC is clearly unconstitutional. If the definition of a PAC and one other major deficiency in the law on reporting of independent expenditures by non-PACs are addressed, we estimate that the score for Kansas would rise to 83%, the second-best free speech score in the nation on campaign finance laws.

While improvements are urgently needed to protect free speech, there are several good features in the existing Kansas campaign finance law. In particular, its definitions of “contribution” and “expenditure” are much better than in most states and follow the U.S. Supreme Court’s precedents. The cabining of speech regulation to express advocacy also is praiseworthy.

The Only Recognized Purpose of Campaign Finance Laws is Preventing Quid Pro Quo Corruption or Its Appearance

It can be easy to lose sight of what is really being regulated and what is really at stake when discussing campaign finance law. Campaign finance law is complex and often esoteric. At first blush, it looks like any other regulatory scheme. But campaign finance regulation is fundamentally qualitatively different from other forms of government regulation. It concerns issues at the heart of democratic self-governance: when and how we discuss issues of public policy and candidates for public office.

“In a republic where the people are sovereign, the ability of the citizenry to make informed choices among candidates for office is essential, for the identities of those who are elected will inevitably shape the course that we follow as a nation.”[1] Therefore, “[t]he First Amendment ‘has its fullest and most urgent application precisely to the conduct of campaigns for political office.’”[2]

Too often, people discuss campaign finance regulations in terms of what they think might be better or worse for their preferred values. But the framers of the Constitution already made the decision to “err on the side of protecting political speech rather than suppressing it.”[3]

The government should not and cannot constrain the right of the American people to discuss candidates and policies lightly. The “Court has recognized only one permissible ground for restricting political speech—the prevention of ‘quid pro quo’ corruption or its appearance” —and “consistently rejected attempts to restrict campaign speech based on other legislative aims.”[4]

Whether through deliberate choice or bureaucratic inertia, many provisions of federal and state campaign finance laws have drifted away from this basic purpose. While better than many states, Kansas is no exception.

The Definition of a PAC

As we were preparing our Free Speech Index, we noticed the enforcement action taken by the Kansas Governmental Ethics Commission (KGEC) against Fresh Vision Overland Park, which illustrates several of the problems with the existing PAC definition.

This action arose because Kansas law on what makes a group a PAC is extremely difficult to understand. The KGEC attempted to use punishment of Fresh Vision to guide groups in the future on how the rules would apply to their activities. We believe that using enforcement to provide guidance is unfair and harms vital First Amendment rights. Worse, in the process, the KGEC adopted an interpretation of the rules that is indefensible.

Pursuant to Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 79 (1976), an organization may only be subject to the full panoply of PAC regulations if it has the “major purpose” of nominating or electing candidates for office.

The Court held that:

To fulfill the purposes of the Act, the [definition of “political committee”] need only encompass organizations that are under the control of a candidate or the major purpose of which is the nomination or election of a candidate. Expenditures of candidates and of “political committees,” so construed, can be assumed to fall within the core area sought to be addressed by Congress. They are, by definition, campaign-related.

But when the maker of the expenditure is not within these categories—when it is an individual other than a candidate or a group other than a “political committee”—the relation of the information sought to the purposes of the Act may be too remote.

(Emphasis added.)

Candidate campaign committees and political parties clearly fit the bill, but civil society is full of organizations that are engaged on public affairs but that do not have the major purpose of electing candidates (examples would include the ACLU, the NRA, the American Dental Association, the National Association of Realtors, labor unions, trade associations, and community groups). Additionally, laws must not be unconstitutionally vague.[5]

Neither the law nor the Commission’s regulations, however, provide an understandable definition of “a major purpose,” a key phrase in the current law defining a political committee, or PAC. That’s a constitutional problem. The courts have repeatedly made clear that laws must give “persons of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited.”[6]

Both the Kansas statutes and the Commission failed to do that. The closest thing to a clear standard in the Commission’s regulation is that any person or group with “the intent” of becoming a PAC is a PAC. But that wasn’t the case with Fresh Vision, whose mission is working for a better community. Indeed, Fresh Vision intentionally tried to avoid becoming a PAC. Yet the KGEC pursued Fresh Vision. So what does it mean to have the “intent” of becoming a PAC, and who makes that decision—the speaker or the KGEC? How can a speaker intend on becoming, or not becoming, a PAC when the definition of a PAC is otherwise so murky?

The other standards in the KGEC’s PAC regulation, Kan. Admin. Regs. § 19-21-3(a) are hopelessly vague. These are presumably the standards a group would use in deciding whether it wanted to—that is, intended to—become a PAC, but this vagueness creates serious problems. Whether a group is a PAC, for example, is based on “the amount of time devoted to the support or opposition of one or more candidates for state office” or “the amount of expenditures … made on behalf of any candidate, candidate committee, party committee or political committee” and similar factors.

But what portion of time? Does it include volunteer time (that the statute prohibits)? What portion of the group’s expenditures? And over what timeframe is this decided? A year? A two-year election cycle? Some other period?

Neither the statute nor the Commission’s regulation – provide answers. Grassroots advocacy groups deserve clear guidance – in advance – about how the law regulates their speech and what they can and cannot do consistent with the law.

This is known as the major purpose test, and Kansas law should be updated to comply with the Supreme Court’s First Amendment ruling. This update requires that Kansas have a reasonable and clear definition of what constitutes “the major purpose” needed to become a political committee. If the Commission had written a regulation interpreting the current law in a manner that respected the Buckley precedent, then amending the statute would be unnecessary. Unfortunately, the KGEC made the law even worse through its vague regulation that adds even more uncertainty to an already ambiguous statute.

We suggest a definition of “political committee” in Exhibit 1 of our statement, which is modeled after the definition adopted by the Arizona Citizens Clean Elections Commission. (See page 31 of their rules here.)

How Much Spending Triggers an Evaluation of Political Committee Status?

No citizen or group should have to register or report to the government before spending a few hundred dollars on flyers, a billboard, or Facebook ads urging their fellow citizens to vote for or against a candidate.

But in Kansas today, if you and your spouse spend one dollar to expressly advocate for the election or defeat of a candidate, the law says you have become a PAC. That is, if a married couple sends first-class letters to two persons urging them to vote for a candidate, they must register with the state.

Similarly, if two people went to a store, purchased a marker and poster board, wrote “Smith for State Senate” on the poster and displayed it at a campaign rally, they would be required under Kansas law to appoint a treasurer, register as a PAC, and report their contributions and expenditures.

These two examples show how ridiculous and unconstitutional it is to define a PAC as a group that spends any money at all.

In Federal Election Commission v. Massachusetts Citizens for Life, Inc. (“MCFL”), 479 U.S. 238 (1986), the Supreme Court held that such grassroots operations may not be forced to register as PACs. The justices were troubled by the burdens placed upon nonprofit organizations by the reporting requirements of political committee status. Some were concerned with the detailed recordkeeping, reporting schedules, and limitations on fundraising required by federal laws regulating PACs. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote specifically to address the law’s “organizational restraints,” including “a more formalized organizational form” and a significant loss of funding availability.

In Coalition for Secular Government (CSG) v. Williams, 815 F.3d 1267 (10th Cir. 2016), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, which includes Kansas and so is binding on federal courts in the state, held that an organization’s planned activity of $3,500 (approximately $4,500 adjusted for inflation) was impermissibly low for triggering Colorado’s regulation of an organization as a PAC for ballot measures, given the associated reporting requirements.

Unquestionably, the Kansas PAC definition and the zero-dollar threshold are unconstitutional under several precedents. We recommend an increase to at least $5,000. After the CSG ruling, the Colorado Legislature adopted a law requiring only postcard registration for groups that anticipate spending more than $200 but less than $5,000 in an election, with full reporting only for groups spending more than that amount.

The federal threshold for PACs and local party committees is $1,000 in a calendar year, and the Federal Election Commission’s (FEC) current legislative recommendations urge that “Congress increase these thresholds to $2,000, and then index those amounts for inflation to prevent erosion in the future.”

Other states have better options. Nebraska, for example, only requires PAC registration and reporting once a group receives more than $5,000 in contributions or makes over $5,000 in expenditures. Some states go farther, like Georgia, which sets its threshold at $25,000.

The best way to avoid forcing groups engaged in minimal advocacy for or against candidates from having to register and report as PACs is to set a reasonable dollar threshold and index that threshold to inflation. Kansas does neither.

Definition of Coordination

Current law states (§ 25-4148c(d)(2)) that an “independent expenditure” is one “made without the cooperation or consent of the candidate or agent of such candidate intended to be benefited and which expressly advocates the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate.”

Unfortunately, the law lacks a definition of “cooperation or consent.” If a candidate or his agents know about an expenditure, what must that candidate do to be presumed not to “consent?” Must he publicly denounce his supporters? If asked about the effort, can he say he is “grateful for their support?” What does it mean for a candidate and an individual, a civic organization, a union, or a trade association to “cooperate?” Can it include responding to public inquiries? Private inquiries? These vague terms chill speech. Without a reasonable definition, speakers are left without coherent guidance about what speech and behaviors are done in “cooperation or consent.” This impermissibly restricts the First Amendment rights of those seeking to speak independently.

The “First Amendment right to speak one’s mind…on all public institutions includes the right to engage in vigorous advocacy no less than abstract discussions,” Buckley (1976) (quoting New York Times v. Sullivan (1964)) and crucially, “independent advocacy” does not “pose [the] dangers of real or apparent corruption comparable to those identified with large campaign contributions.” Buckley (1976). Independent speech has a treasured history in our country, and clear demarcations from the Legislature should protect the right.

Here, federal regulations at 11 C.F.R. §109.21 provide an example of how to clarify the type of conduct that can constitute coordination. This clarity protects speakers from inadvertently violating the law while ensuring independent expenditures remain independent.

Additionally, the statute should include several safe harbors, including one for publicly available information. If a speaker uses information available to everyone to develop a communication, that could not constitute coordination. Federal regulations state that a communication is not coordinated “if the information material to the production, or distribution of the communication was obtained from a publicly available source.”[7]

We suggest a definition of “cooperation or consent” in Exhibit 2 of our statement.

Donor Disclosure for non-PACs

Under current law, it is unclear if general donor disclosure is required on independent expenditure reports for groups that are not PACs. The law should be clarified, and the better rule is that only donors of funds earmarked for political activity should be disclosed. General disclosure of donors to organizations that make limited political expenditures tends to mislead the public both as to the amounts being spent and the true sources of financial support for political ads.

Only donors of funds “for the express purpose of nominating, electing or defeating a clearly identified candidate for a state or local office” and expenditures that are “made to expressly advocate the nomination, election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate for a state or local office” should be required to be disclosed.[8] But it is unclear whether donor disclosure on independent expenditure reports is, in fact, subject to this limitation.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United that all U.S. citizens and organizations have a First Amendment right to urge people to vote for or against candidates. But most groups do not exist solely for that purpose. From time to time, general advocacy groups may want to speak or publish information to support or oppose the election of a candidate, even if such speech is not normally its primary goal. The First Amendment protects such speakers. Advocating for candidates cannot be reserved solely for candidates, parties, and groups registered as political committees.

An organization that makes periodic independent expenditures but does not qualify as a PAC should not have to sacrifice its privacy or the privacy of all its supporters. The more state law treats groups that make some independent expenditures like full-fledged political committees, the less they will engage in campaign speech.

Courts have recognized that occasional campaign speech cannot be regulated with the same strictness and severity placed upon organizations whose major purpose is candidate advocacy. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, sitting en banc, struck down a law requiring independent expenditure funds to have “virtually identical regulatory burdens” as PACs.[9]

This lack of clarity in the Kansas statutes regarding what donors must be disclosed should be corrected. This can be easily done by adding a few lines to the current Kan. Stat. Ann. § 25-4150. If the underlined text that appears below is added, that will resolve the uncertainty in the current law:

25-4150. Contributions and expenditures by persons other than candidates and committees; reports, contents and filing. Every person, other than a candidate or a candidate committee, party committee or political committee, who makes contributions or expenditures, other than by contribution to a candidate or a candidate committee, party committee or political committee, in an aggregate amount of $100 or more within a calendar year shall make statements containing the information required by K.S.A. 25-4148, and amendments thereto during any reporting period when contributions or expenditures are made. With respect to the information required by K.S.A. 25-4148(b)(2), the person (if other than a natural person) shall be required to report only funds the person has received that are earmarked (a) for the express purpose of nominating, electing or defeating a candidate or candidates for a state or local office; or (b) to expressly advocate the nomination, election or defeat of a candidate or candidates for a state or local office. Such statements shall be filed in the office or offices required so that each such statement is in such office or offices on the day specified in K.S.A. 25-4148, and amendments thereto. If such contributions are received or expenditures are made to expressly advocate the nomination, election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate for state office, other than that of an officer elected on a state-wide basis such statement shall be filed in both the office of the secretary of state and in the office of the county election officer of the county in which the candidate is a resident. If such contributions are received or expenditures are made to expressly advocate the nomination, election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate for state-wide office such statement shall be filed only in the office of the secretary of state. If such contributions or expenditures are made to expressly advocate the nomination, election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate for local office such statement shall be filed in the office of the county election officer of the county in which the name of the candidate is on the ballot. Reports made under this section need not be cumulative.

Enforcement: The Problem of Unreasonable Interpretations of Campaign Finance Laws

Campaign finance laws place significant burdens on First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly. While courts have allowed some regulations, they have consistently placed boundaries on the extent of such regulation.

Bipartisanship is indispensable in an enforcement agency whose core function is regulating political speech, particularly in the context of elections. A partisan structure risks the reality or appearance of a referee with his thumb on the scale of the contest, using its immense regulatory power for partisan gain. Fortunately, Kansas is one of only a few states that attempts to ensure bipartisan enforcement.

This is not enough to ensure fairness, however. In Kansas, it is often hard to understand some of the campaign finance laws. Partly this is due to the way the laws are written, but it is also due to KGEC regulations. The average person or organization simply does not have the resources to understand complex laws, and as the Supreme Court has ruled, “[t]he First Amendment does not permit laws that force speakers to retain a campaign finance attorney” to determine whether and how they may speak.[10] Rather, laws and rules regulating speech about government should speak for themselves; they should be clear on their face in “giv[ing] the person of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know” how his or her speech will be regulated.[11]

As one court put it, “in this delicate first amendment area, there is no imperative to stretch the statutory language, or read into it oblique references of congressional intent.”[12] Yet we see regulators often stretching the law, including in Kansas.

The problem is that regulators frequently take the most speech-restrictive view of the law. It is as if they view that as their role as an advocate. But that is wrong. Regulators shouldn’t use enforcement to provide clarity on a vague law. That is unfair.

The Legislature should consider spelling out a presumption of free speech in the law, such as “The Commission shall have the most reasonable reading of the law in any enforcement action. To the extent a law is vague or ambiguous, the least speech-restrictive interpretation should prevail.” Such a rule would match the Supreme Court’s admonition that “in a debatable case, the tie is resolved in favor of protecting speech.”[13]

Speakers need to know, in advance, what the law restricts or regulates. Ideally, the legislature would update vague laws. The KGEC should have a duty in the statute to bring vague and ambiguous language needing clarity to the Legislature’s attention.

Facing a complaint not only burdens free speech through a “chilling effect,” it also creates a public stigma against that speaker. It creates huge additional costs from paying an attorney to defend your activities.

When he served on the FEC, Bradley A. Smith kept a file of letters from people trapped by campaign finance laws. All believed they performed a civic duty by working on a campaign. Most didn’t have attorneys. One letter summed up their anger: “I will NEVER be involved with a political campaign again.”

We need to encourage responsible citizens to get involved in election campaigns, not to shun engagement for fear of running afoul of unnecessarily complicated laws. Passing complex laws with intimidating enforcement methods discourages this vital First Amendment activity.

An Internet Exemption Like the One Written by the FEC Is Desirable

The internet empowers the average person to initiate and participate in movements for political and social change and to challenge power and authority. For example, while democracy remains a work in progress in the Middle East, social media played a prominent role in popular uprisings against autocratic regimes in the region several years ago. Closer to home, the “Tea Party,” “Women’s March,” and “Me Too” campaigns were fueled by the pervasive and personal reach of social media.

The FEC’s “internet exemption,” adopted in 2006, continues to set the appropriate framework for regulating online political speech. Under this exemption, online political speech generally is unregulated unless it is in the form of paid ads.

Before the internet exemption, many online speakers ran the risk of legal complaints, investigations, and penalties. In enacting the agency’s “internet exemption,” the FEC recognized the internet is unique in that:

-

-

-

- it “provides a means to communicate with a large and geographically widespread audience, often at very little cost”;

- “individuals can create their own political commentary and actively engage in political debate, rather than just read the views of others”; and

- “[w]hereas the corporations and other organizations capable of paying for advertising in traditional forms of mass communication are also likely to possess the financial resources to obtain legal counsel and monitor Commission regulations, individuals and small groups generally do not have such resources. Nor do they have the resources . . . to respond to politically motivated complaints in the enforcement context.”[14]

-

-

Here is the text of the FEC’s internet exemption:

The term general public political advertising shall not include communications over the internet, except for communications placed for a fee on another person’s website, digital device, application, or advertising platform.

As you can see, under the FEC’s rule, paid internet advertising is subject to regulation. Other forms of online communications, such as creating, maintaining, or hosting a website; Facebook posts; Twitter tweets (now X posts); YouTube uploads; or “any other form of communication distributed over the internet” are not regulated.

Grassroots Advocacy Should Not Be Regulated

The First Amendment says in part that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging . . . the right of the people . . . to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The act of petitioning for redress of grievances has deep American roots, going back to pamphleteers like Thomas Paine’s now-famous Common Sense. It is celebrated in our culture, from the paintings of Norman Rockwell to the town council meetings on television shows. The Supreme Court has said the right to petition the government is “among the most precious of the liberties safeguarded by the Bill of Rights.”[15]

Grassroots advocacy, also called “grassroots lobbying,” is a term used to describe efforts to exercise petition rights. Grassroots advocates organize citizens, urge them to contact government officials, and educate the public in an effort to affect public policy in a classic American style. Grassroots advocacy includes activity as simple and common today as groups of people attending a city council meeting in colorful matching t-shirts to demonstrate to public officials strong public support for (or opposition to) a proposed bill.

University of Missouri economist Jeffrey Milyo explains the importance of grassroots lobbying:

Would‐be grassroots lobbyists face an inherent difficulty known in political science literature as the problem of collective action: Oftentimes, self‐interested individuals do not have a sufficient incentive to take actions that would be in the interest of a group of people. Political participation is rife with such problems, from voting and contributing to candidates to contacting legislators about issues of shared concern. . . .

One lesson that emerges from scholarly research is that political entrepreneurs can solve the collective‐action problem. More effective groups are those where some members care enough about the group to take on the cost of coordinating, communicating and mobilizing other individuals. These groups become organized and function as interest groups. . . . [G]rassroots lobbyists rely on patrons and contributors to provide resources to inform, coordinate and mobilize group members.

Seen in this light, the frequent assumption that authentic grassroots lobbying can only occur absent political entrepreneurs and professional expertise is simply ridiculous. Unorganized and ordinary citizens with legitimate and latent preferences for policy cannot be expected to monitor the legislative calendar constantly just in case an item of concern should pop up; nor can ordinary citizens be expected to fully comprehend the legislative process so that they can contact the appropriate committee members at the appropriate time. Advocacy groups and other entrepreneurs provide a valuable function for unorganized interests by monitoring legislation and sending action alerts when appropriate, as well as helping to coordinate grassroots action for maximum effect by informing people about the issues at hand, the relevant actors to contact and the time frame for action.[16]

In short, grassroots advocacy is vital to representative democracy in action.

Some states seek to regulate these organizations and their activity under grassroots lobbying laws that impose regulatory burdens on this vital right. Many small or new groups aren’t even aware that such a law would regulate such a quintessentially American activity.

One way to partially mitigate the impact of grassroots lobbying laws (aside from eliminating all such laws) is to have a high spending threshold for the activity that protects smaller campaigns, which may not even be aware of such requirements. Yet the threshold in Kansas is just $1,000, which is trivial for a statewide effort.

States with grassroots lobbying laws that clearly identify what activities will trigger reporting obligations better protect issue advocacy from running afoul of these laws. One basic metric is whether regulation is based on speech that references specific legislation. Again, the Kansas law fails to do even that.

Political Parties Are Critical to Our Political System

Political parties play an important role in our political system. They help people come together and work for common goals. But they are at a large disadvantage in Kansas, nationally, and in some states.

For example, independent expenditure-only committees are able to raise and spend unlimited amounts of money, while state and local party organizations are subject to strict limits on how much they can raise. While interest groups are generally good for society and self-government, many focus only on one issue, or a narrow range of issues. Historically, political parties have been meliorating institutions that balance a wide variety of views and interests in broad coalitions. Treating political parties as inferior to other groups and organizations in society makes politics more atomized, more focused on individual candidates, and less of a team sport.

Kansas should consider joining the majority of states nationally that do not limit individual contributions to political parties. This would allow parties to compete with Super PACs and could reduce complexity.

A Word About Contribution Limits

One of the most important avenues through which citizens can voice their political preferences, contributing to candidates and causes, is restricted in many ways across the country. The right to contribute to candidates, parties, and political groups allows citizens to simply and effectively join with others to amplify their voices and advocate for change.

Many people mistakenly believe that most states limit all types of campaign contributions. Historically, states have not limited contributions for most of our nation’s history, and even today most states permit citizens to donate any amount in at least one of the categories we studied in our 2018 scorecard titled “Grading the 50 States on Political Giving Freedom.”

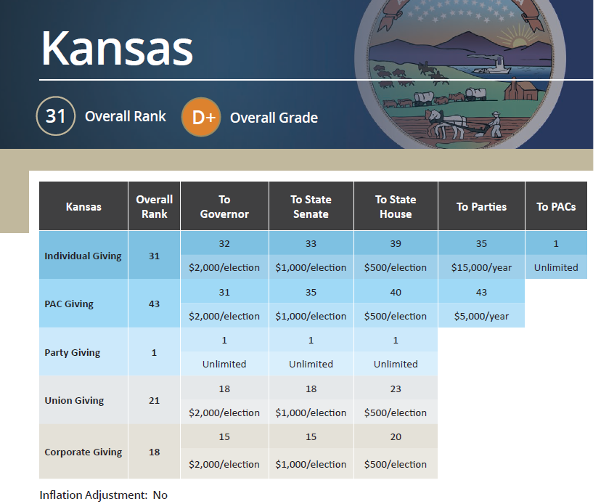

Kansas scored poorly in our 2018 scorecard on contribution limits, ranking 31st overall. The state is well below average on contribution limits to political parties – indeed, as of the date studied in the report, 28 states allowed unlimited individual contributions to political parties.

Contribution limits tend to lead to complexity as states seek to avoid “loopholes.” States without contribution limits, on the other hand, have less need for complex rules on coordination or giving through intermediaries.

The right to speak out about politics is a core First Amendment right, and limits on one’s political donations infringe on that right. The Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled that campaign spending limits are unconstitutional. Despite explicity recognizing that contributions limits also infringe on First Amendment rights, see Buckley, 424 U.S. at 22, the Court has nonetheless upheld carefully-crafted limits on contributions to candidates, political parties, and PACs. But that doesn’t mean such limits are good policy. And the Court ruled in 2006 that even candidate and party contribution limits can be unconstitutionally low, as when it struck down limits in Vermont in 2006 and in Alaska in 2019.[17]

While limits on contributions impede political engagement and discourage some donors from participating altogether—a bad thing, we believe—other individuals merely look for other ways to express their political opinions and preferences. Thus, besides limiting speech, limits distort and make more opaque and mysterious the ways in which individuals participate. In particular, limits give politically active individuals an incentive to contribute to independent groups, such as super PACs, that can fundraise and spend without such limits. As the Supreme Court has found it unconstitutional to limit contributions to and expenditures from independent groups, contribution limits place candidates and political parties at a permanent political disadvantage. Kansas should consider substantial increases in, or even elimination of some or all of its contribution limits. At a minimum, the Legislature should consider an increase in contribution limits to account for inflation since the last adjustment. That should be coupled with automatic inflation adjustments to prevent erosion of the limits by inflation.

Those who argue for contribution restrictions say such infringements benefit democracy. They maintain that unlimited contributions will increase corruption, shut out citizens who lack significant financial resources from the political process, drive up the cost of campaigning such that new candidates cannot compete with incumbents, and allow wealthy contributors to “buy” special favors from public officials.

But a varied and extensive collection of academic research finds little evidence for these claims. This research shows that: (1) there is “no strong or convincing evidence that state campaign finance reforms [including contribution limits] reduce public corruption;” (2) limits often do more harm to individuals’ constitutionally protected First Amendment rights to participate in the political system than is justifiable; (3) contribution limits stifle the speech of political entrepreneurs – the individuals and organizations who form and grow new political voices and movements; (4) contribution limits have little effect on voter turnout and, in so doing, fail to place more electoral power in the hands of everyday citizens; (5) individuals, not so-called “special interests,” are the main source of campaign contributions; (6) contribution limits add to the inherent advantages of incumbency; and (7) campaign contributions do not “buy” politicians’ votes, as legislative voting patterns have not changed with changes to campaign contributions.[18]

The Institute for Free Speech has also found no relationship between a state’s limits on contributions from individuals to state legislative candidates and its quality of government management as determined by the Pew Center on the States. In fact, two of the top three best-governed states have no limits at all on how much may be given to candidates from any source.[19]

Adjust All Monetary Amounts for Inflation

A dollar today is worth less than a dollar in the past. Yet Kansas campaign finance law sets monetary thresholds in fixed dollar amounts, and these amounts are not regularly updated. These thresholds run the gamut, from how much spending triggers reporting requirements to how large a contribution must be to require reporting of a contributor’s personal information. Because of this system, regulations unnecessarily capture ever smaller groups, more private information, and more speech over time. Adjusting these thresholds for inflation is a simple and uncontroversial way for states to acknowledge that small speakers and contributors need not be regulated by the government. It would also ensure that the value of contribution limits is not reduced over time by inflation.

What Impact Does Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta (“AFPF”) have on Campaign Finance Laws?

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2021 ruling in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta (“AFPF”) will have a substantial, positive impact on the rights of Americans to keep their memberships, volunteer work, and financial support for causes and organizations private. This landmark legal precedent is already being implemented by federal courts to evaluate donor disclosure and campaign finance laws. In large part, it incorporates and builds on previous precedents.

Sometime in 2010—the exact date is uncertain—then-California Attorney General Kamala Harris began demanding that charities and other nonprofits file IRS Form 990, Schedule B with the state as a condition of remaining “registered,” and thus legally able to solicit contributions, in the state. Schedule B is a simple but, because of its content, highly sensitive form. It is an annual list of names, addresses, and amounts given by major donors (over $5,000 or two percent of an organization’s income) to a charity or other nonprofit. By statute, the IRS is prohibited from making this information public, and while nonprofits must make Form 990 available for public inspection, they may redact the names and addresses of donors from any public inspection.

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court held that the California rule violated the First Amendment right to freedom of association. Encompassed within the freedom of association is a right to keep one’s memberships, affiliations, and financial support private. Chief Justice Roberts, joined by Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett, wrote the Court’s opinion finding California’s policy unconstitutional, with Justice Alito (joined by Justice Gorsuch) and Justice Thomas concurring in most of the opinion and the judgment, but writing separately on the question of the standard of review. Justices Sotomayor (joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan) dissented.

Before the Supreme Court’s decision, several commentators, and some amici in the case, suggested that the decision would jeopardize campaign finance disclosure laws. In dissent, Justice Sotomayor wrote, “[t]oday’s analysis marks reporting and disclosure requirements with a bull’s-eye,” presumably referring to reporting and disclosure mandates for political campaign spending.

The NAACP v. Alabama[20] line of cases notwithstanding, since the 1976 decision in Buckley v. Valeo, the Supreme Court has often upheld campaign finance disclosure laws. The Court has traditionally recognized three “important” state interests supporting these laws, none of which were present in AFPF: (1) providing information needed by the government to enforce political campaign contribution limits; (2) preventing corruption by exposing possible quid pro quo exchanges of public acts for campaign contributions; and (3) an “informational” interest in helping “voters to define more of the candidates’ constituencies,” and, therefore, “the interests to which a candidate is most likely to be responsive.”

Political campaign disclosure laws have historically been evaluated under the “exacting scrutiny” standard. To the extent that the decision in AFPF puts more teeth into that standard of review, some laws could be suspect. For example, many states, including Kansas, require reporting of campaign contributions at very low levels. Laws requiring public disclosure of such small sums may be subject to challenge as not “narrowly tailored” to any of the important state interests, recited above, that the Court has recognized. That said, the core of campaign finance disclosure laws – disclosure of large contributions to candidates and other political committees – are likely to remain untouched barring a major change in the Court’s jurisprudence.

Given the narrow scope of the interests supporting compulsory disclosure, however, the Court has limited mandatory disclosure to the narrow category of ads directly related to political, and particularly candidate, campaigns. Except when dealing with “political committees” —organizations whose “major purpose” is the election or defeat of candidates (essentially PACs, political parties, and candidate campaigns) —the Court has only upheld compulsory disclosure laws that are closely and directly tied to candidate campaigns. Disclosure of donors and members of organizations engaged in general public advocacy are typically protected from mandatory disclosure.

What Campaign Finance Laws Might Be Unconstitutional After AFPF?

In addition to any broad requirement that all or most nonprofit organizations disclose their donors, either publicly or to the government, we have identified several types of laws in Kansas that may be subject to constitutional challenge after AFPF. Here are examples of requirements that now rest on shakier constitutional ground than before:

-

-

- Requirements that an organization making “independent expenditures” disclose all donors rather than only those who earmarked contributions for the expenditures;

- Requirements that groups without “the major purpose” of promoting the election or defeat of candidates be registered as political committees or subject to the same broad disclosure; and

- Laws requiring filings by groups engaged in “grassroots lobbying” on issues and pending legislation.

-

Conclusion

When discussing political speech, it’s important to remember that we are dealing with the essence of what it means to live in a free society—the ability to discuss candidates and ideas for how we want to be governed. When in doubt, government should always err on the side of freedom. Some modest but important changes to state campaign finance law would achieve that goal and enhance free speech rights in Kansas.

Exhibit 1

(l) (1) “Political committee” means any entity, including a combination of two or more individuals who are not married to one another, or any person other than an individual, the primary purpose of which is to make contributions or expenditures as defined by this act of more than $2,500 during a calendar year.

(A) As used in this paragraph, “primary purpose” means the entity meets at least one of the following standards:

(i) The entity states in its articles of incorporation, bylaws, or resolutions by the board of directors that its primary purpose is to elect state or local candidates through express advocacy and contributions to candidate campaigns and political parties; or

(ii) the entity spends at least 50% of the entity’s total program spending on contributions or expenditures as defined by this act during a two-year general or local election cycle.

(B) “Total program spending” includes all disbursements for contributions and expenditures and the costs of fundraising communications that expressly advocate the nomination, election, or defeat of a candidate or candidates for state or local office, but does not include:

(i) volunteer time or expenses;

(ii) administrative expenses; or

(iii) other fundraising expenses.

(C) For purposes of determining “total program spending,” grants to other organizations shall be treated as follows:

(i) A grant made to a political committee or an organization organized under section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code shall be counted in total program spending and as a contribution or expenditure, unless expressly designated for use outside Kansas or for federal elections, in which case such spending shall be counted in total program spending but not as a contribution or expenditure.

(ii) If the entity making a grant takes reasonable steps to ensure that the transferee does not use such funds to make a contribution or expenditure in Kansas, such grant shall be counted in total program spending but not as a contribution or expenditure.

(iii) If the entity making a grant expressly earmarks a portion of the grant for a contribution or expenditure in Kansas, the grant shall be counted in total program spending and the earmarked portion of the grant shall count as a contribution or expenditure.

(2) Notwithstanding paragraph 1 above, the Commission may nonetheless determine that an entity is not a political committee if, taking into account all the facts and circumstances of grants made by an entity, it is not persuaded that the preponderance of the evidence establishes that the entity is a political committee.

Exhibit 2

Add to the definitions in K. S. A. 25-4143:

“Cooperation or consent,” means:

(A) an express advocacy expenditure is either created, produced, or distributed at the request or suggestion of a candidate, candidate committee, or party committee; or

(B) the person paying for the expenditure, and the candidate, candidate committee, or party committee assents to the request or suggestion of the person. Such assent leads to coordination only when the person paying for the expenditure (1) consults with the candidate, candidate committee, or party committee about the expenditure, and (2) the candidate, candidate committee, or party committee assents before the expenditure is made.

(C) Safe harbors. Cooperation or consent does not include:

-

-

-

- A candidate’s or a political party’s response to an inquiry about that candidate’s or political party’s positions on legislative or policy issues;

- An expenditure for which the information material to the creation, production, distribution, or undertaking of the expenditure was obtained from a publicly available source;

- An endorsement of a candidate;

- Soliciting contributions for a candidate or party committee;

- A finding based solely on the use of a commercial vendor or a former employee of the candidate by the person paying for the communication, when the commercial vendor or former employee has provided political services to a candidate during the previous 120 days if a firewall is established and implemented by the person paying for the communication, and the firewall is designed and implemented to prohibit the flow of information between employees or consultants providing services for the person paying for the expenditure and those employees or consultants are currently providing or previously provided services to the candidate; and

- A finding based solely on the use of a commercial vendor or former employee of the candidate who has not provided political services to the candidate within 120 days.

-

-

[1] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 14-15 (1971).

[2] Federal Election Commission v. Cruz, 142 S.Ct. 1638, 1650 (2022) (quoting Monitor Patriot v. Roy, 401 U.S. 265, 272 (1971)).

[3] Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc., 551 U.S. 449, 457 (2007).

[4] Cruz, 142 S.Ct. at 1652 (quoting McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, 572 U.S. 185, 207 (2014) (plurality opinion)).

[5] Buckley, 424 U.S. at 44-45.

[6] Grayned v. Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 108-109 (1972); see also Buckley, 424 U.S. at 77; United States v. Harris, 347 U.S. 612 (1954).

[7] 11 CFR§ 109.21(d)(2).

[8] See Kan. Stat. Ann. § 25-4143(e)(1)(B) (defining “contribution”).

[9] Min. Citizens Concerned for Life, Inc. v. Swanson, 692 F.3d 864, 872 (8th Cir. 2012) (en banc).

[10] Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310, 334 (2010).

[11] Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 108 (1972).

[12] Federal Election Commission v. Machinists Non-Partisan Political League, 655 F. 2d 380, 394 (D.C. Cir. 1981) (quoting Richmond v. United States, 275 U.S. 331 (1928)).

[13] Fed. Election Com’n v. Wisc. Right to Life, 551 US 449, footnote 7.

[14] See FEC, Explanation and Justification for Final Rules on Internet Communications, 71 Fed. Reg. 18,589 (Apr. 12, 2006) at at 18,590-18,591.

[15] United Mine Workers of America, District 12 v. Illinois State Bar Association, 389 U.S. 217, 222 (1967).

[16] Jeffrey Milyo, Ph.D., “Mowing Down the Grassroots: How Grassroots Lobbying Disclosure Suppresses Political Participation,” Institute for Justice. Available at: https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/mowing_down_the-grassroots.pdf (April 2010).

[17] Randall v. Sorrell, 548 U.S. 230 (2006); Thompson v. Hebdon, 140 S.Ct. 348 (2019); see also Thompson v. Hebdon, 7 F. 4th 348 (9th Cir. 2021)

[18] Adriana Cordis and Jeff Milyo, “Working Paper No. 13-09: Do State Campaign Finance Reforms Reduce Public Corruption?,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: mercatus.org/sites/default/files/Milyo_CampaignFinanceReforms_v2.pdf (April 2013), p. 2.

Melanie D. Reed, “Regulating Political Contributions by State Contractors: The First Amendment and State Pay-to-Play Legislation,” William Mitchell Law Review, Vol. 34:2. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: http://www.ifs.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/reed2007paytopay.pdf (February 2008).

Jeffrey Milyo, Ph. D., “Keep Out: How State Campaign Finance Laws Erect Barriers to Entry for Political Entrepreneurs,” The Institute for Justice. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: http://www.ifs.org/doclib/20101001_Milyo2010ContribReport.pdf (September 2010).

David M. Primo and Jeffrey Milyo, “The Effects of Campaign Finance Laws on Turnout, 1950-2000,” Department of Economics and Truman School of Public Affairs, University of Missouri. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: http://economics.missouri.edu/working-papers/2005/wp0516_milyo.pdf (February 2006).

Stephen Ansolabehere, John M. de Figueiredo, and James M. Snyder Jr., “Why is There so Little Money in U.S. Politics?,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 17:1. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: http://tinyurl.com/nlvrun9 (Winter 2003).

Joel M. Gora, “Buckley v. Valeo: A Landmark of Political Freedom,” Akron Law Review, Vol. 33:1. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: http://www.ifs.org/doclib/20101217_Gora1999Buckleyv.Valeo.pdf (January 1999).

Stephen G. Bronars and John R. Lott, Jr., “Do Campaign Donations Alter How a Politician Votes? Or, Do Donors Support Candidates Who Value the Same Things that they Do?,” The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. XL. Retrieved on June 24, 2016. Available at: http://www.ifs.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Bronars-1997-Money-And-Votes.pdf (October 1997).

[19] Matt Nese and Luke Wachob, “Do Lower Contribution Limits Produce ‘Good’ Government?”, Institute for Free Speech (then known as the Center for Competitive Politics), available at: https://www.ifs.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/2013-10-08_Issue-Analysis-6_Do-Lower-Contribution-Limits-Produce-Good-Government1.pdf (2013).

[20] In 1956, as part of an investigation into whether NAACP was conducting business in violation of the state’s foreign corporation registration statute (and really, as part of the state’s efforts to hamper the NAACP’s work for civil rights), Alabama’s attorney general demanded that the organization hand over a list of names and addresses of its supporters to state officials. The NAACP refused and was held in contempt by Alabama state courts. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed, writing:

It is hardly a novel perception that compelled disclosure of affiliation with groups engaged in advocacy may constitute [an] effective [] restraint on freedom of association…. Inviolability of privacy in group association may in many circumstances be indispensable to preservation of freedom of association, particularly where a group espouses dissident beliefs….

Under these circumstances, we think it apparent that compelled disclosure of petitioner’s [] membership is likely to affect adversely the ability of petitioner and its members to pursue their collective effort to foster beliefs which they admittedly have the right to advocate.

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449, 462-463 (1958).