This week, Senate Democrats unveiled their plan to get favorable media coverage this election season: grandstand on a package of nonstarter proposals to radically expand laws regulating political speech. (I guess because it worked so well in 2014?)

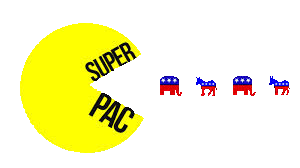

If the proposals are sincere, they are also woefully misguided. The rollout of the talking points gave us the chance to hear its authors make fools of themselves by misrepresenting the law and the role of money in politics. For example, a press release outlining the various (still unseen) provisions promises to “rein in the ‘dark money’ Super PACs,” which is odd because such groups don’t exist. Super PACs publicly report the names, addresses, employers, and occupational information of all their donors over $200, just like candidates, political parties and other PACs do.

Perhaps more worrisome, however, were comments by Minnesota Senator Al Franken. From The Huffington Post:

Without naming names, Franken pointed to the case of Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Kan.), who briefly broke with his party to support holding hearings on President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland.

Well-funded outside groups threatened to run ads and support challengers to Moran because of his statements, and he reversed himself to oppose hearings.

“Doesn’t that appear like corruption? To anybody? I see members of the press nodding, involuntarily. It’s amazing,” Franken said.

First of all, is it common for journalists today to cheer along with politicians’ press conferences? Perhaps I should stop being mystified when media outlets uncritically repeat myths about money in politics.

But more importantly, the answer to Franken’s rhetorical question is “no.” Spending money to inform voters of a candidate’s views – or “threatening” to do so – is not corruption. It is speech. Note that Senator Franken does not accuse the groups of misrepresenting Moran’s position. He simply accuses them of publicizing it. Where’s the corruption in that?

Imagine a different Senator and a different issue. Suppose a Democratic Senator planned to vote against a climate change bill, upsetting the Sierra Club and other environmental groups. Suppose those groups told the Senator that if she followed through, they would run ads in her state publicizing her vote and supporting her challenger. The Senator, aware that her constituents care deeply about climate change, changes her mind and supports the bill. Would Senator Franken and other critics of Senator Moran’s reversal on hearings for Judge Garland see corruption here too? I doubt it. More likely they would laud the environmental groups for holding an elected official accountable.

Consider, too, what would happen if we prohibited advocacy groups from engaging in campaign speech and advertising, as Franken and his allies seem to desire. Would their influence disappear? Of course not. The same groups that spoke out against Moran could still exert political pressure, whether by paying for lobbyists to do it behind closed doors or by hammering him through press organizations, which are exempt from campaign finance laws. Either outcome is worse for speech and democracy – and heck, transparency too – than simply allowing groups to purchase political ads. These ads, rather than relying on the skill of your lobbyist or your access to a sympathetic media company, succeed or fail based on their ability to persuade voters. Isn’t that how democracy is supposed to work?

A Senator whose actions are restrained by a wealthy few, as Senator Franken apparently sees it, would indeed be a concern. A Senator whose actions are restrained by the will of the voters, on the other hand, is a model for how government is supposed to function. Senator Moran’s reversal on hearings for Judge Garland appears to be a case of the latter.

The fact is no amount of spending could unseat Moran or any other elected official if the voters supported him. Evidently, Moran feared too many voters would not and changed course. That’s not corruption, that’s democracy. Unfortunately, that’s what’s at risk when politicians decide to rewrite the rules governing political speech. If groups are stifled in their ability to publicly support, oppose, laud and criticize candidates, actual corruption will only worsen as officeholders are shielded from scrutiny and voters are left in the dark.