Super PACs came into existence in 2010 – that’s twelve years ago. They have spent roughly $5 billion dollars since that time, leaving their mark on six different election cycles.

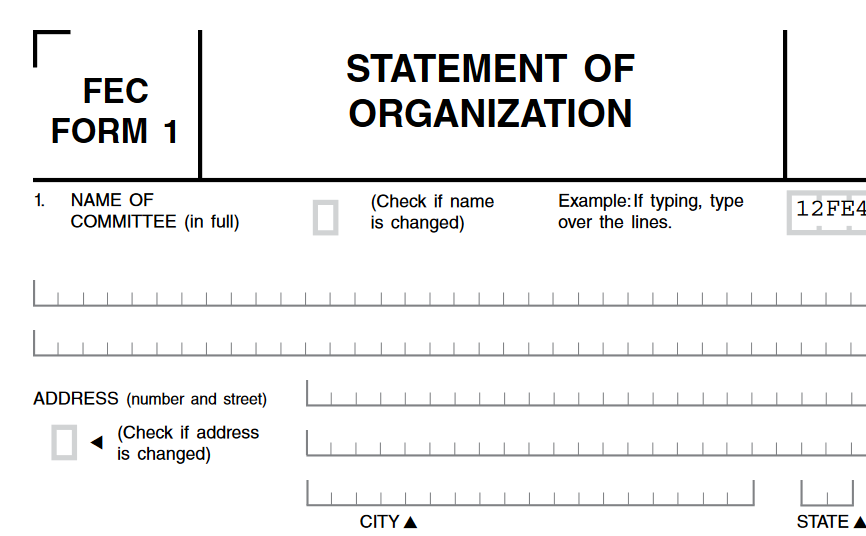

On Thursday morning, the Federal Election Commission finally decided to include them on its registration forms.

That may sound odd to those who are not familiar with the FEC. How could all that time and money pass without the government so much as creating a form for super PACs? The answer reveals much about the Federal Election Commission, what ails it, and hopes for a brighter future.

The FEC was created in the wake of the Watergate scandal to enforce the nation’s campaign finance laws. Since regulating campaign activity could so easily be abused by partisan actors, no more than three of the Commission’s six members may belong to any one political party. This bipartisan structure also forces the commissioners to work across party lines and gives credibility to the FEC’s actions.

Of course, the potential downside of forcing the parties to work together is that sometimes, they would rather not. For most of the Commission’s history, that hasn’t been a big problem. But Congress grew derelict in replacing commissioners at the end of their terms, allowing personal animosities to deepen as many served long past the six years for which they were chosen. Then, as a string of Supreme Court rulings reshaped the legal landscape for campaign finance law between 2007 and 2014, those strained relationships hampered the Commission’s ability to keep up.

Specifically, the FEC’s Democrats strongly opposed the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United or the D.C. Circuit Court’s ruling in SpeechNow that same year. Those decisions led to the creation of independent expenditure-only committees, better known today as super PACs. These groups advocate the election or defeat of federal candidates but do not contribute to candidates or parties, nor do they coordinate their efforts with them. As a result, they are not subject to the contribution limits that apply to donations to candidates and traditional political action committees (hence the “super” in “super PAC”), although they still must follow many other campaign finance rules, such as publicly reporting their donors and expenditures to the FEC.

Unable to overrule the courts or persuade Congress to change the law, the FEC’s Democrats could have accepted reality and changed the forms. Instead, they took their ball and went home. For years, Democratic commissioners refused to amend FEC forms to acknowledge super PACs unless the Republican commissioners offered a concession in return. The Republicans refused in kind, feeling that amending Commission paperwork to reflect current law was a basic responsibility of the agency, not the opening of a negotiation.

For the feds, doing nothing – or next to nothing – is always an option. So the registration process for these newfound political entities, which raise and spend billions of dollars each election cycle, was ultimately developed – in the words of Commissioner Ellen Weintraub at Thursday’s meeting – “out of something that Commissioner McGahn and I scrawled on a napkin in a conference room.”

For twelve years, that was the best the FEC would do. Anyone looking to start a super PAC was left to fill out the regular political action committee registration form, then attach a cover letter stating their intention to operate as an independent expenditure-only committee. It’s almost comical. If you want to start a super PAC, get your stapler ready.

Notably, as awkward as this arrangement has been, it hasn’t appeared to stop anyone from starting a super PAC. It just confuses the process and makes a mockery of the Federal Election Commission.

So that’s the bad news: the FEC has too often been mired in personal disputes and delusions about the scope of its power to function as well as it should. The good news is that Thursday’s vote suggests the Commission’s problems are not unsolvable. Progress is possible.

Newly elected Chair Allen Dickerson, who put the motion on Thursday’s agenda, noted at the meeting that the FEC last year cleared a historic number of enforcement matters. The Commission is capable of functioning when it wants to. It has simply too often lacked the quorum or the decorum to set its sights where they belong.

The newfound progress at the FEC cannot be separated from the infusion of new faces at the Commission. Four of the six current commissioners have served for less than two years. Congress should keep the momentum going by replacing the remaining overstay commissioners who have served long past their term. Commissioner Weintraub, for instance, will this year celebrate her 20th year in a position that carries a six-year term.

Amending the FEC’s PAC registration form to acknowledge super PACs (and hybrid PACs) may not be a huge accomplishment. It may not even be a big or moderately sized accomplishment. But that’s sort of the point.

The FEC has too often failed to get the small things right. Let’s hope that’s starting to change.