The 2016 election will conclude next week, but efforts to establish an interpretative narrative of it have already begun. After failing to make their cause a key issue of the campaign, supporters of greater government regulation of political speech have unsurprisingly begun to paint 2016 as an election year in which shady plutocrats further consolidated their grip on the American political system. Case in point: The Huffington Post’s “Money in Politics” reporter, Paul Blumenthal, has written that “The super-rich have managed to increase their influence on elections, even though the 2016 presidential race will cost less than the previous one, reversing a longtime trend.”

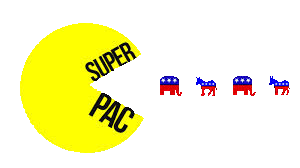

The latter two clauses of that sentence already indicate why it is strange to believe this particular election cycle is breaking new ground in “Money in Politics.” But Mr. Blumenthal’s focus is on “mega-donors,” and much-reviled “super PACs.” “Total super PAC contributions from donors giving $500,000 or more now tops $1 billion ― about 15 percent of the estimated $6.6 billion cost of this year’s federal elections,” Blumenthal notes. This is compared to $444 million in spending from such donors to date in 2012.

The overarching fallacy of this piece is the simplistic assumption that more spending automatically translates to more electoral influence. Super PACs – formally known as Independent Expenditure-Only Committees – primarily spend money on advertising advocating for a specific candidate or issue. Their influence in an election is limited to how effective those ads are at persuading voters, who ultimately decide the outcomes of elections. Advertising is of course an important way to educate voters about candidates and issues. Yet, as anybody following politics can attest, the constant barrage of advertising during an election year can sometimes be more irritating than convincing.

Indeed, after studying the 2012 election, political scientists John Sides and Lynn Vavreck found that political ads had a small and short-lived effect on voter attitudes that disappeared within a week. Other academics have found that negative advertising – which has risen along with independent political spending – is not an effective means of winning votes, though it “tends to be more memorable and stimulate knowledge about the campaign.” Furthermore, political advertising has the difficult task of persuading an ever-smaller pool of undecided voters. In short, more super PAC spending does not necessarily represent more influence, and there are diminishing returns on each additional dollar spent.

This is easily observable to those outside of academia too. Just ask soon-to-be President-elect Jeb Bush how his significant super PAC support won him the keys to the White House.

It’s not as if super PACs are pushing nefarious, unheard-of agendas either. As Blumenthal acknowledges, “Both parties in this year’s election are benefitting [from super PAC support], with money from mega-donors almost evenly split. Republican donors giving $500,000 or more have provided $488 million. Democratic mega-donors have given $479 million.” Yes, much like voters tend to be closely divided between major party candidates, so are super PACs. It turns out “mega-donors” are people too.

This competitive spending race between existing, mainstream viewpoints is vibrant among super PACs as it is elsewhere in politics, and some groups support candidates from both parties, and even third party options: “An additional $44 million has been given by donors supporting Libertarian Gary Johnson for president, or those whose contributions are divided between the two major parties,” Blumenthal reports.

The historical example of Eugene McCarthy illustrates how political contributions can foster diversity of opinion rather than drowning it out. Thanks to the early support of a few wealthy supporters, McCarthy’s insurgent 1968 campaign for the Democratic nomination caused the withdrawal of an unpopular sitting U.S. president from the race and fundamentally altered the character of a major political party. New perspectives can become popular if given the opportunity to be heard by voters – and discouraging political participation prevents this chorus of voices.

Blumenthal’s sinister characterization of independent expenditure groups overestimates their influence in American elections, and overlooks the positive role they can play in fostering greater debate, educating voters, and providing alternative viewpoints. At the end of the day, however, this is a matter of free speech. Citizens do not relinquish their First Amendment rights simply because they choose to join in concert with other like-minded individuals. Blumenthal’s piece is neither the first nor the last that will try to fearmonger about political spending. It is important, however, that history interprets the 2016 election based on facts rather than preconceived narratives.