Multiple news accounts, including this one in Sunday’s Washington Post, report that President Donald Trump’s shortlist includes U.S. Appeals Court Judge Amy Coney Barrett of Indiana, U.S. Appeals Court Judge Thomas Hardiman of Pennsylvania, U.S. Appeals Court Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh of Maryland, U.S. Appeals Court Judge Raymond Kethledge of Michigan, and U.S. Appeals Court Judge Amul Thapar of Kentucky. Kethledge and Hardiman were finalists for now-Justice Gorsuch’s seat, and both were once clerks to retiring Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Last year, we analyzed Judge Kethledge (here) and Judge Hardiman (here and also here). It is often difficult to definitively compare the records of any two judges because they rule on different cases, and that is true here.

Kethledge’s opinions, or those he joined, were often outstanding. As noted by David Keating in the analysis, “Lavin v. Husted is one of the best I’ve read in preparing these reports. Kethledge’s careful scrutiny of a contribution ban is outstanding. In re US harshly rebuked IRS tactics in a case filed after the IRS Tea Party targeting scandal. In contrast to Lavin, Bailey v. Callaghan is disappointing because it fails to apply careful scrutiny to a law that targeted one union for disparate treatment due to its policy views.” Also, in Bible Believers v. Wayne County, Mich., “Kethledge joins [a] thorough opinion about the First Amendment’s application to the ‘heckler’s veto.’”

Kethledge’s opinions cover a substantial range of free speech cases, and he normally applies rigorous scrutiny, except as noted above in the union case.

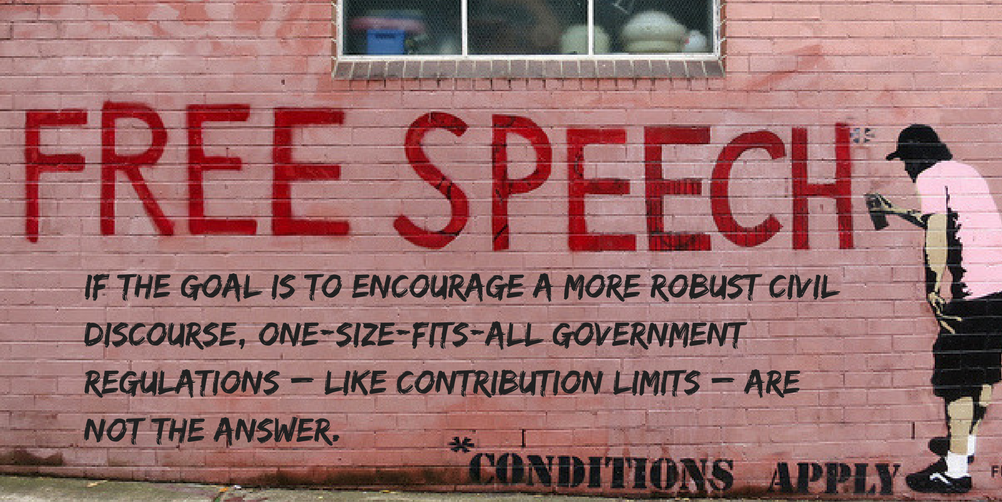

The Post article reports that “Trump has said it is essential his nominee be ‘not weak,’ meaning someone with independent judgment and the courage to buck ‘the political and social fashions of the day,’ as the adviser put it… Trump [also] privately says he wants a nominee who will ‘interpret the Constitution the way the framers meant it to be…’” Between these two judges on the opinions we have reviewed, Kethledge appears to meet those two criteria better than Hardiman on First Amendment free speech issues.

Since our reports last year, both Hardiman and Kethledge each joined one opinion on a substantial First Amendment question. (UPDATE, July 6: We recently became aware of another opinion joined by Judge Kethledge in 2012. A summary of that opinion appears later in this post.) We review these opinions below.

Hon. Raymond Kethledge

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit (2008-Present)

Jones v. Coleman, 848 F. 3d 744 (6th Cir. 2017)

Judge Raymond Kethledge joined an opinion reviewing the constitutionality of a provision in the Tennessee Campaign Financial Disclosure Act.

Tennessee defines a political action committee as “a combination of two (2) or more individuals… to support or oppose any candidate for public office.” The Tennessee Ethics Commission enforced that provision against Williamson Strong, a very small, grassroots group that spent less than $500, and imposed a $5,000 fine.

As noted in the opinion, several parents formed a “group called the Association for Accurate Standards in Education (“AASE”). AASE opposed another group of parents advocating for removal of a social studies textbook that includes discussion of Islam from the public schools in White County…. Approximately five or six people have donated to AASE since its formation, but no individual donation has exceeded $200; indeed total donations to AASE have yet to reach $500.”

In short, AASE was very similar to Williamson Strong. Unsurprisingly, when the AASE learned of the other group’s $5,000 fine, they became very concerned their group would face the same fate. So it held off on its plans to spend less than $250 on independent expenditures to “to support and oppose candidates for at least two seats on the [local] Board of Education” and filed this lawsuit.

“After full briefing and oral argument,” noted the opinion, “the district court stayed the case pending the outcome of the state administrative proceedings in the Williamson Strong case, and opining as well that the Act’s application represented an unclear question of state law that, once interpreted by state courts, could eliminate the potential First and Fourteenth Amendment violations.” AASE then filed an appeal on the lower court’s decision to abstain.

The lower court’s decision was clearly in error, and the solid opinion patiently reviews the abstention doctrine and AASE’s standing in the ruling to reverse the district court. While the opinion remanded the case to the district court “or further proceedings consistent with this opinion,” the opinion sent strong hints that AASE should win.

From the opinion (internal citations omitted):

[T]he district court reasoned that, eventually, the final resolution of the Williamson Strong case will provide clear answers regarding the application of [the law] to groups like AASE, perhaps avoiding a First Amendment problem.

But the district court’s reasoning, like a house built on sand, cannot stand. The district court’s reliance on Williamson Strong to clarify the scope of [the law] is a fatal flaw in its analysis because this issue is not before the administrative law judge in the Williamson Strong proceedings…. Because the parties do not dispute the threshold issue of whether Williamson Strong is a political campaign committee under Tennessee law, it is far from guaranteed that the resolution of Williamson Strong will correspondingly resolve any unclear issues of state law that might eliminate the federal constitutional questions in the present case….

Moreover, we do not find [the law] to be so ambiguous as to necessitate abstention…. The district court did not analyze whether [the law] might be subject to an interpretation that does not violate the First Amendment; rather, it adopted a wait-and-see approach relying on a different case that is centered around a different issue. This, we conclude, was error. We imagine that the district court would have been hard-pressed to find an interpretation of this statute that satisfies the First Amendment, but because the district court passed on the opportunity so to do, we do not rule on the issue….

Although we decline to reach the merits of the parties’ arguments today, we echo the Supreme Court’s strong aversion to the invocation of Pullman abstention when a state statute is being challenged on First Amendment grounds and when that statute is not obviously susceptible to a limiting construction….

Separate and apart from the free-speech problems with applying Pullman abstention here, when the plaintiff has requested preliminary injunctive relief, a district court ought ordinarily to grant it when it abstains. “As we see the matter… the abstention order did in effect deny preliminary injunctive relief and effectively shut the federal courthouse door upon plaintiffs in their search for timely vindication of their federal constitutional claims.”

Bays v. City of Fairborn, 668 F. 3d 814 (6th Cir. 2012)

(UPDATE, July 6: We recently became aware of another opinion joined by Judge Kethledge in 2012.)

While reading a post by Wen Fa on Judge Kethledge, we realized we had missed an interesting and well-reasoned opinion he joined that was written by Judge Eugene Edward Siler Jr. Wen Fa does a nice job summing up the case:

[In this case] the police threatened to arrest two people who were walking around a festival with a sign conveying a Christian message. The city defended its actions, pointing to a ban on the “soliciting of causes outside of booth space” during the Sweet Corn Festival. The city argued that the ban was necessary for crowd control, but it identified no crowd concerns at the festival. Judge Kethledge fully joined the opinion striking down the law. In so doing, he found the ban far too restrictive, since it prohibited all signs, leaflets, and even one-on-one discussions.

The opinion applied careful scrutiny to the restrictions, which were upheld by the district court. The appeals court also remanded the case with an instruction to grant the request for a preliminary injunction.

Hon. Thomas Hardiman

United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit (2007-Present); United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania (2003-2007)

Wilmoth v. Secretary of The State of New Jersey, (3rd Cir. 2018)

Judge Thomas Hardiman joined an opinion that reviewed the constitutionality of a law banning out-of-state petition circulators under the First Amendment in this case.

The opinion is marked “not precedential,” but it is a solid analysis that vacates and remands a clearly flawed district court ruling to dismiss the case. The plaintiffs challenged “a New Jersey law requiring that persons circulating petitions on behalf of candidates for national office be residents of New Jersey…. Appellants argue that the law in question, N.J. Stat. Ann. § 19:23-11, imposes an impermissible burden on their First Amendment right to engage in core political speech.”

From the opinion (some internal citations omitted):

[Our] inquiry in the instant case is quite straightforward. Since the turn of the century, “a consensus has emerged” that laws imposing residency restrictions upon circulators of nomination petitions “are subject to strict scrutiny analysis….”

Our sister courts’ collective agreement on this issue has its genesis in Meyer v. Grant, where a unanimous Supreme Court held that Colorado’s criminalization of paid petition circulators amounted to an unconstitutional restriction on “core political speech.” 486 U.S. 414, 422 (1998). In so holding, the Court emphasized that “the circulation of a petition involves the type of interactive communication concerning political change” for which First Amendment protection “is at its zenith….”

The plain language of [the law] makes clear that one’s residency is the sine qua non for determining whether he or she may lawfully circulate nomination petitions in New Jersey. Specifically, the relevant portion of the statute states that “[t]he person who circulates the petition shall be a registered voter in this State whose party affiliation is of the same political party named in the petition.” (emphasis added). New Jersey seeks to inoculate the “in this State” language by arguing that the statute, as a whole, should be more appropriately regarded as imposing a “party affiliation” restriction, not a residency restriction. See, e.g., (Appellee’s Br. 21) (“[T]his Court should… uphold the party affiliation requirement in [the law] as justified by ‘important regulatory interests.’”) (quoting Timmons, 520 U.S. at 358). This argument, however, is unavailing. Wilmoth and Pool are dues-paying members of the Democratic and Republican Parties, respectively, yet remain barred under [the law] from circulating nomination petitions in New Jersey. Their party affiliations, in other words, are immaterial; instead, it is the fact that they reside out of state that prevents them from circulating petitions. Because New Jersey’s residency requirement for circulators restricts “core political speech,” strict scrutiny review is warranted….

Having determined that strict scrutiny applies, the burden now shifts to New Jersey to prove (1) that its stated interests in upholding the constitutionality of [the law] are compelling and (2) that the statute is narrowly tailored to advance those interests….

Here, New Jersey argues that [the law] serves two compelling interests…. Our inquiry, however, does not end with a determination that “the Government’s asserted interests are important in the abstract.” Turner Broad. Sys., Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 646 (1994). Instead, “[w]hen the Government defends a regulation on speech as a means to redress past harms or prevent anticipated harms, it must . . . demonstrate that the recited harms are real, not merely conjectural, and that the regulation will in fact alleviate these harms in a direct and material way….” [B]ecause the District Court granted New Jersey’s motion to dismiss prior to discovery taking place, the parties were not afforded an opportunity to develop an evidentiary record, and thus we have no basis upon which to gauge the validity of the competing interests at stake.

The complaint in this action presents a plausible claim that the New Jersey law infringes out-of-state circulators’ First Amendment rights. Accordingly, we will vacate the order dismissing this action and remand to allow the parties to develop an appropriate factual record for the purposes of determining whether the New Jersey law does in fact violate the Appellants’ constitutional rights.