Bloomberg BNA recently covered a report highlighting a developing trend in campaign finance this election cycle. The report, by the Campaign Finance Institute (CFI), shows a clear decrease in political fundraising for presidential candidates and parties in 2016, coupled with an increase in super PAC spending, compared with 2012. Total fundraising in support of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump reached $851.5 million on June 30, 2016, while there was nearly $1.1 billion in combined receipts for Barack Obama and Mitt Romney at the same point in their campaigns.

There are several factors that can explain this decrease. For one, the Republican primary featured a historically high number of candidates, dividing donor money between them. Trump had insisted early on that he would not court large donors, and refrained from doing so until June, when he had effectively won the Republican nomination. Donor money was also split between multiple Democratic candidates this year, while incumbent President Obama ran unopposed in the 2012 primaries. Public polling numbers about both Clinton and Trump could also be the cause for decreased donor enthusiasm, but these explanations represent only the tip of the iceberg.

When Bloomberg BNA spoke with CFI’s Executive Director, Michael Malbin, he described an “even wider disillusionment with politics among campaign contributors as a whole,” noting that “total fundraising for congressional candidates and most party committees also is down this year from previous levels, something that has rarely, if ever, happened before.” Indeed, the DNC is down in its fundraising, and both parties have much less cash on hand than they did at this point four years ago. In addition, the RNC, though performing better than the DNC in total fundraising, has had to bear greater costs in supporting Trump’s minimalist campaign.

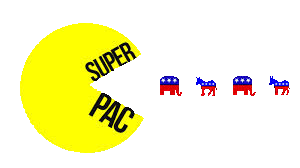

At the same time, independent expenditures have doubled since 2012, from $225 million to $576 million. To opponents of super PACs, this is horrible news – in their view, it marks a drift towards deep-pocketed corporate interests playing an ever-greater role in shaping political debate. If this increase in independent expenditures tells us anything however, it’s that politically active donors are not sitting out because of a “wider disillusionment with politics,” but rather that many are continuing to participate in political discourse by other means.

Facilitating the growth in this spending are recent Supreme Court (and circuit court) rulings that have allowed for the creation of super PACs, but that spending has likely become such a prominent feature in American politics because many donors believe it is simply the best way to speak about a candidate. Federal law currently limits individual contributions to candidates at $2,700 per election ($5,400 combined for both primary and general elections). Giving to PACs is capped at $5,000 per year and national parties at $33,400 per year (with exceptions for specified party accounts that can accept larger donations). PACs are similarly limited in their contributions to candidates and parties, while other entities like businesses, unions, and advocacy groups are prohibited from contributing to candidates and parties at all.

Although some of these contribution limits may appear high to the average voter, they are ultimately arbitrary and severely underestimate both the cost of effective political speech, especially on a national scale, and donors’ willingness to contribute money to political activities – as evidenced by the many contributors who are seeking out other ways to participate.

We are living with the practical consequences of these regulatory incentives. Traditional political actors, such as candidates and parties, are increasingly seeing their public platform encroached by ads from independent groups. Some candidates have tried to harness the potential of independent expenditures by outsourcing advertising and other operations to friendly super PACs, but this has proven to be difficult in practice, given the illegality of direct coordination between the two entities.

Even for those who don’t believe that contribution limits curtail free speech rights (in spite of Supreme Court precedent noting that limits do infringe upon First Amendment rights but are justifiable to prevent corruption or the appearance of corruption), this is a practical dilemma. Limiting one type of contribution will inevitably give rise to new, unforeseen methods, which is exactly how traditional PACs and bundling of donations originally entered the political lexicon decades ago.

Regulatory activists should ask themselves who they prefer to be the main actors in political discourse: candidates, parties, PACs, independent groups, or some other group. The instinct to simply contain all of them is not a viable option, as engaged citizens will continue to innovate new participation strategies, and tacking on new regulations to such innovations will continue to stifle free speech. Regulatory whac-a-mole is not an effective solution.

We at CCP support the First Amendment rights of everyone to speak and associate as they wish – be it contributing to a candidate, forming a super PAC, or something else entirely. But for those fearful of the influence of super PACs in American politics, more de-regulation of laws limiting support for candidates and parties may be the best way to reduce their prominence.