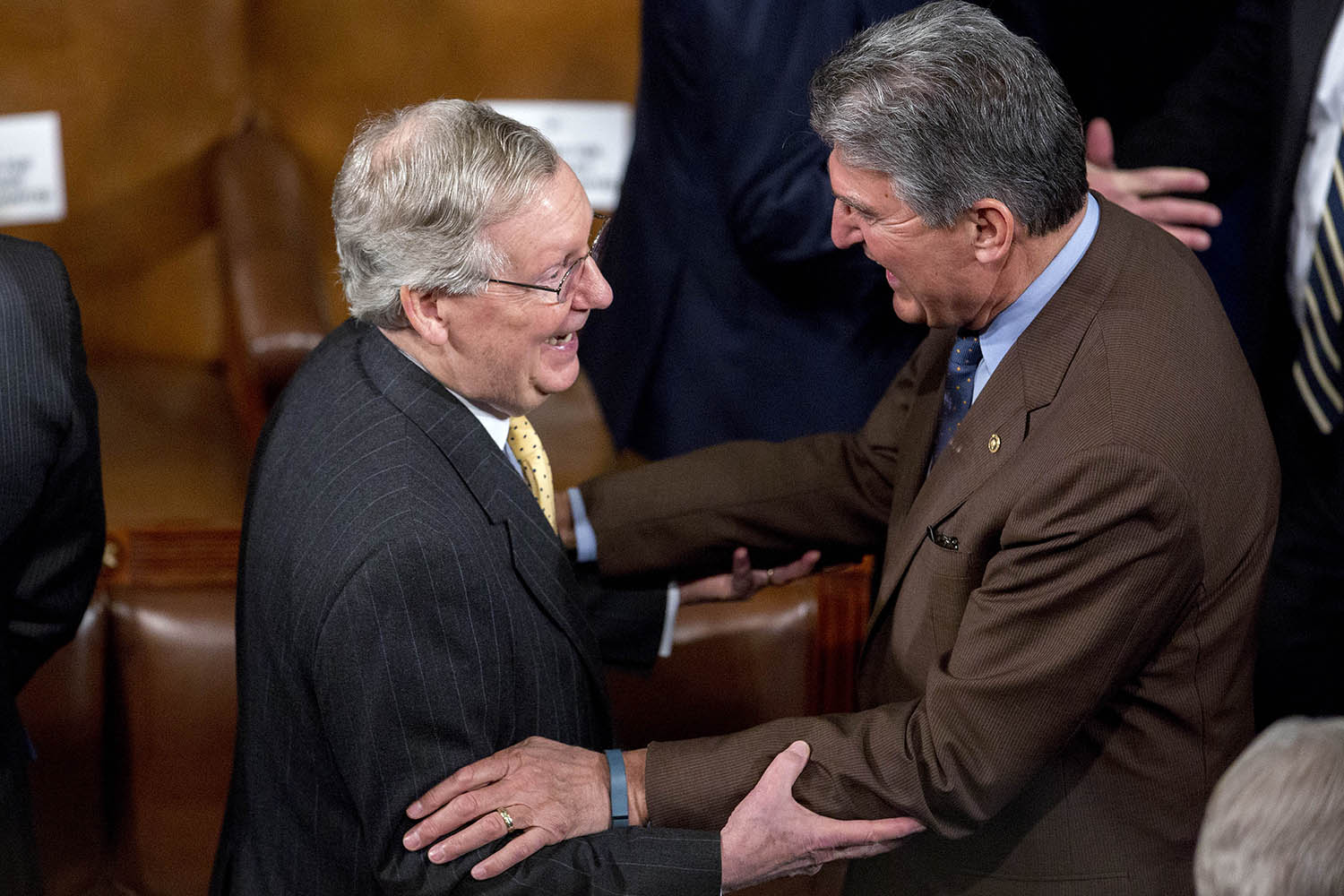

Members of Congress don’t get along much these days. Americans are well aware that they live in a time of great partisan division, one of the consequences of which is Congress’s continual inability to function efficiently. Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia thinks he has a solution: a pledge that sitting senators not campaign against each other.

The non-binding pledge would have five conditions for senators that accept:

- No campaigning against sitting colleagues.

- No direct fundraising against colleagues (including for Senate campaign groups).

- No distributing direct mail against colleagues.

- No appearing in or endorsing ads directed at colleagues.

- No using or endorsing social media campaigns attacking colleagues.

Supporters point out that senators generally did not take to the campaign trail to bash their colleagues until the past two decades. It’s true such activity could be making interparty cooperation more difficult, as lawmakers hold grudges against specific individuals who tried to run them out of office. Take this step to repair personal relationships between senators, the theory goes, and soon they will find it easier to work together.

Would following these rules make Congress more collegial and efficient? Possibly. But what is certain is that such an arrangement would do more to prop up incumbent politicians at the expense of their challengers and critics. As long as it makes their lives easier during campaign time, politicians might think it’s good for politics as a whole.

One obvious implication of this pledge is that, were senators to stop campaigning against each other, their time, resources, and attention would likely become more focused on shutting out critics who are outside of the Senate, like electoral challengers, nonpartisan advocacy groups, and other political outsiders. Fresh-faced candidates often rely on more recognizable allies to establish a brand and compensate for their own low profile, but without that support, incumbents can dominate the conversation by virtue of their office, media contacts, franking privileges, record of legislative accomplishments, and likely fundraising prowess.

Similar arrangements have been put into practice in the past, like the so-called “People’s Pledge” or the “No PAC Caucus.” Such agreements help insulate lawmakers from criticism and allow party and government elites to monopolize political discourse. Worse yet, they often seek to institutionalize these rules – turning them from voluntary pledges into pseudo-contracts or, eventually, concrete campaign finance policy. At that point, such pledges not only make government less accessible to political outsiders, but they begin to limit the freedom of lawmakers to speak their mind or conscience at the risk of crossing their colleagues.

Politics has enough empty grandstanding – from bashing “out-of-state donors,” to misrepresenting donations from employees of a specific industry, to spreading misinformation about “dark money.” We shouldn’t add to that by stigmatizing senators who have the audacity to criticize one of their own. After all, we elect our representatives to engage in important policy debates.

While most Americans may agree that it’s important for the two parties to work together more, the solution is not to stop them from competing with each other. There are numerous ways senators divide each other that are more impactful and worthy of criticism than ordinary campaign activity. A better place to start might be for elected officials to stop accusing each other of treason, for example. Until then, we should be wary of lawmakers who mistake groupthink for unity.