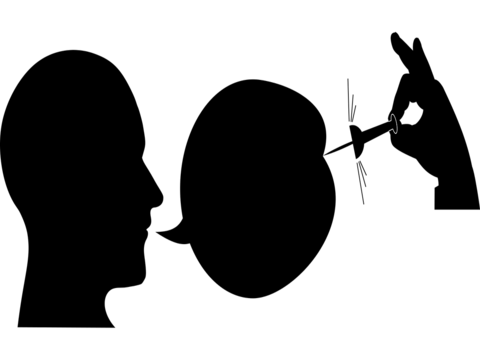

Our political debate has become supercharged with polarization and vitriol. A symptom of this dangerous discourse is the acceleration of what’s now known as “cancel culture,” where people are punished, sometimes viciously, for violating social norms and increasingly fear expressing themselves.

One of the best definitions of “cancel culture” is offered by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, who explains that “cancellation, properly understood, refers to an attack on someone’s employment and reputation by a determined collective of critics, based on an opinion or an action that is alleged to be disgraceful and disqualifying.” Recent cancellations have shown the threat cancel culture poses to free expression and highlight the importance of shoring up a more tolerant society that can ward off the dangerous excesses of cancel culture.

The Pew Research Center discovered in a survey this summer that liberals are more likely to perceive cancel culture as holding people accountable whereas conservatives are more likely to view cancel culture as an unjust form of punishment. While certain individuals are rightfully held accountable for their actions, today we are witnessing too many excesses that flow from social intolerance.

Although critiques of cancel culture are most prominent on the political right, it is important to recognize that cancel culture is also a threat to the reputations and careers of people on the left. Recently, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a journalist for The New York Times Magazine who received a MacArthur Fellowship and Pulitzer Prize for her work on The 1619 Project, was denied tenure at UNC for what appeared to be conservative backlash to her political views and theories. (After backlash to the backlash, Hannah-Jones was ultimately offered tenure and declined the offer.) Associated Press journalist Emily Wilder was fired in May 2021 for tweets she made as a college student that were very critical of Israel and prominent individuals who supported Israel. Last year, analyst David Shor was fired from his job at the progressive consulting company Civis Analytics simply for tweeting an academic study surveying public opinion on violent and nonviolent protests. Earlier this year, a Stanford Law Student was investigated and temporarily had a hold placed on his ability to graduate for posting a satirical flyer mocking the Stanford Federalist Society. Far from mere examples, both Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic and Kat Rosenfield, in a book review at UnHerd, have authored thoughtful pieces about the danger cancel culture will ultimately pose to progressive thinkers and activists. In each of the above cases, individuals were unfairly punished and had their careers put in jeopardy merely for expressing political opinions.

Concerns over cancel culture are not isolated to academia or a select group of journalists or analysts. Indeed, many Americans are worried about the impacts of cancellation on their careers and everyday lives. A Harvard CAPS-Harris poll conducted in March 2021 found that 64% of respondents believe a “growing cancel culture” is threatening their freedom with 36% of respondents agreeing that cancel culture is a “big problem.” Additionally, the poll found that 54% of those surveyed were “concerned” that sharing their opinions online could result in their being banned from social media or fired by their employer. These findings reinforce the conclusions of a summer 2020 Cato Institute poll establishing that 62% of Americans have political views that they are afraid to share in the current political climate. The Cato poll further revealed that this opinion is shared across the political spectrum and various identity groups.

So, if cancel culture is a threat regardless of your political leanings, what can we do about it? First, we should focus on building a more tolerant culture that provides people with a degree of latitude to test out ideas and make mistakes without worrying about long-term impacts on their careers. The Emily Wilder case exemplifies this idea. Wilder should have been free to have strong opinions in college without those views compromising her ability to have a promising journalism career. There may be exceedingly rare and egregious cases where one’s past political views or actions should impact their current career, but this should only be a very narrow exception to a strong general rule. Likewise, aspiring academics should not feel compelled to endorse a political orthodoxy to receive tenure. In short, we can all do our part to be more welcoming to diverse ideas and viewpoints, especially those with which we disagree.

The tragedy of the cases above is that politics has been forcefully imposed on the personal lives of individuals. Generally, people should have a private sphere of their lives where they can hold personal political views without those beliefs compromising their career. We want people to be civically engaged, to express themselves, and to be involved in our political system. However, if the costs of civic engagement are too great, citizens will decide not to engage in the first place. Privacy can be a shield that encourages people to engage in political discourse and debate while protecting their careers and without exposure to the potential capricious wrath of public opinion.

While building a more tolerant culture is an ideal, it won’t happen overnight. We must reckon with the reality that there are currently deep issues with our polarized culture that are harming individuals and leading to fear and self-censorship. We should take affirmative steps to protect these individuals. The Supreme Court recently took one significant step in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta by recognizing the right of Americans who support nonprofits to privately associate and to not be forced to release private and sensitive donor information to the government. Congress can also do its part to protect citizen privacy by passing the “Don’t Weaponize the IRS Act,” which would limit the amount of unnecessary personal information that the IRS collects about individuals and organizations. Members of Congress should also pass legislation that limits government surveillance of Americans exercising their First Amendment rights, particularly during political protests. In an age of cancel culture, we should be concerned about leaks and the intentional release of personal information that can be used as an impetus for cancellation.

Individuals have also expressed concern about being cancelled or fired for being associated with political candidates and causes they support. Making matters worse, federal campaign contribution laws require an individual’s name, home address, occupation, and employer to be disclosed for a contribution to a candidate as low as $200. Many state laws are more aggressive. Taken together, there are strong reasons for Americans to worry about low donor disclosure thresholds potentially chilling social involvement in public discourse. It is unfair to demand that individuals be publicly associated with political activities for small donations in a cultural climate that poses risks to all individuals across the political spectrum. We should also be cautious about excessive donor exposure due to the past history of misuse, manipulation, and abuse of this information. Instead, disclosure laws should be focused on protecting the privacy and associational rights of average Americans. At a minimum, the current low thresholds for reporting should be increased and indexed to inflation.

Ultimately, cancel culture is a threat to everyone because popular opinion can quickly shift. We would do well to heed James Madison’s timeless warning: “What bitter anguish would not the people of Athens have often escaped if their government had contained so provident a safeguard against the tyranny of their own passions? Popular liberty might then have escaped the indelible reproach of decreeing to the same citizens the hemlock on one day and statues on the next.” Changing our laws and embracing a more tolerant culture are the best ways we can avoid cancel culture becoming a modern-day hemlock for our political discourse.