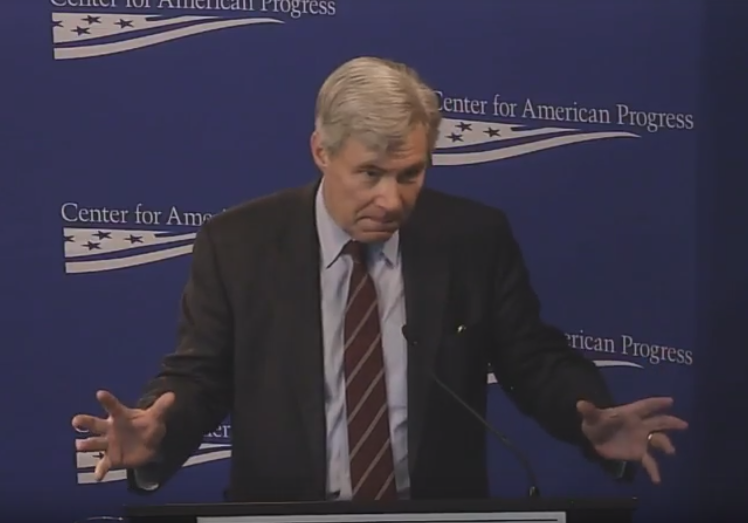

“This is like the Death Star. In Star Wars, they didn’t go fight the evil empire on every single planet. They went after the Death Star, and once they won the Death Star, everything else moved, you know, in a better direction.” That was how Senator Sheldon Whitehouse explained the importance of eliminating so-called “dark money” during remarks at a Monday event at the Center for American Progress.

Never mind that the Star Wars film following the Death Star’s destruction is titled “The Empire Strikes Back,” not “Happily Ever After.” Never mind that the Death Star and its relatives have been destroyed again and again, and the bad guys still seem to wind up in charge. More interesting than the Senator’s clumsy pop culture references – which also included comparing the Republican Party to the farmer in Men In Black who gets killed and possessed by an alien (“that is more or less what’s happened to the Republican Party… it’s Republican skin with these huge special interests inside”) – is his expansive view of what constitutes “dark money.”

To Senator Whitehouse, “dark money” is not just political spending by nonprofit organizations that aren’t required to disclose their donors. In his usage, “dark money” encompasses spending by any organization that seeks to influence political debates or the law while protecting the privacy of its supporters. Indeed, Senator Whitehouse’s remarks included attacks on everything from ad campaigns that support or oppose the confirmation of judicial nominees to the filing of amicus briefs – yes, amicus briefs – as tools for nefarious special interests to corrupt government.

These comments make clear that if advocates for greater regulation of political speech are successful, they will not stop at regulating speech that seeks to influence the outcome of elections. Speech that seeks to influence votes on legislation, or rulings in administrative agencies, or court decisions would all be fair game for government regulation. Or, as Whitehouse put it, “[dark money] is after us in elections, it is after us in administrative agencies, it is after us in the halls of Congress.” And he intends to stop it.

For Americans who want government to listen to them without exposing their personal information to millions of people, however, the real threat comes from politicians like Senator Whitehouse who are working to eliminate privacy from political discourse. Americans already surrender a great deal of their privacy when they participate in politics. Anyone who contributes over $200 to a candidate, political party, political committee, or super PAC has their name, address, occupation, and employer published in an online database that can be searched by anyone with internet access. That means nosy neighbors, potential employers, your landlord, coworkers – you name it.

Many Americans prefer to keep that information private, and many have good reasons for doing so. Some fear retribution from government officials for backing the opposition. Some fear being targeted for harassment by activists and online trolls. Some fear being punished or ostracized by their employer, family members, or neighbors with differing beliefs. Some simply want to avoid being harangued by other candidates and groups asking for contributions.

Thankfully, Americans who want to get involved without getting exposed have ways to participate. Some of the most viable options are joining nonprofit and issue advocacy groups. These groups can help shape public policy through research, communication, litigation, and other techniques that do not involve much speaking about elections. As a result, they are generally spared from the heavy hand of campaign finance regulation.

Senator Whitehouse’s comments, and the general tenor of the event (titled “Dark Money and the Federal Courts: The Secretive Push to Weaponize the First Amendment”), suggest that those days could be numbered. While the focus of the forum was mainly about how so-called “dark money” groups influence the courts, the logic underlying the discussion was startlingly broad: any group that spends money to influence anything relating to public policy should have to disclose its donors.

Disclosure legislation has not had much success at the federal level recently, and has suffered many notable defeats at the state level as well. However, speech-chilling proposals promoted under the guise of “transparency” continue to threaten First Amendment rights in elections, at administrative agencies, and in the halls of Congress. Senator Whitehouse and others are clearly committed to seeing such regulations pass. Supporters of free speech and privacy need to be just as vigilant in defense of their liberties as their opponents are in trying to strip them away.