We live in politically polarized times – that’s about the one thing most Americans can agree on. A more contentious question is what – or who – is causing that polarization. A common view is that Americans themselves have become more polarized, but Stanford political scientist Morris Fiorina sees it another way: he argues in a new book (“Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate”) that it’s the two major parties that have become more polarized, thus uncomfortably forcing an increasingly heterogeneous (but still “moderate”) voter base into two different parties.

Fiorina believes this phenomenon has created an environment where parties compete for “unstable majorities.” Unlike the decades-long advantages parties used to hold over Congress or the White House, their electoral victories are now fleeting. A wave election can easily lead to a dramatic reversal in subsequent contests. Fiorina’s advice is for parties to simply select more moderate candidates in the deep red or blue districts that they normally can’t compete in. But it’s not so simple in practice. He sees political donors as a major reason for this:

This advice has one crucial shortcoming, Mr. Fiorina acknowledges: “They can’t do it.” One reason has to do with money. “The donors are most ideological of all,” he says. In the 1970s and ’80s, “a big majority of contributions to congressional races came from individual contributions within your district, and now the money is coming from outside. Texas is an ATM for Republicans, California and Manhattan for Democrats.”

…The Republican in Oregon, a more liberal state, is likely to prove unelectable. For this problem there is probably no remedy. “The only thing I can see mattering would be unconstitutional,” Mr. Fiorina says—to wit, a law requiring that “all campaign contributions have to come from within the jurisdiction of the race being held.”

Fiorina may well be right that independent groups and ideological donors have shifted the landscape of American politics, and possibly even complicated things for political parties. But he is also correct to hesitate in his policy prescription, though not only for constitutional reasons. Banning donations from outside specific jurisdictions would not be a boon for democracy, but a burden.

Contra Fiorina’s hypothesis about parties being more polarized while voters remain moderate, Americans of all stripes have become far more tribalist in their partisan leanings – Republicans have moved right, and Democrats have moved left. This has slowly eroded the middle ground that used to be shared by conservative “blue dog Democrats” or liberal “Rockefeller Republicans,” and pushed the median Democrat and Republican further away from each other. Another Stanford professor even found that Americans identify more strongly with their political party than they do their race or religion.

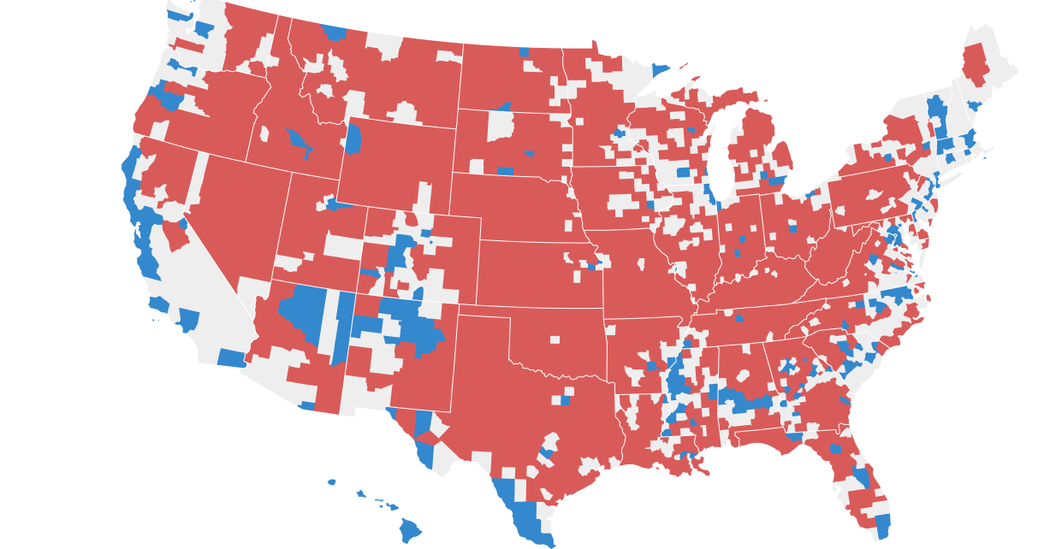

This ideological sorting of parties has led to sorting in other ways too – especially by geography. The RAND Corporation has found that geographic clustering is more responsible for increased polarization in the House of Representatives than even gerrymandering.

Looking at Fiorina’s quote in this light, it’s not hard to see why donors, activists, or other politically engaged Americans might decide to participate in politics outside their own state. Those who do not choose to cluster with other like-minded voters find themselves in a predicament: a conservative in San Francisco or a progressive in rural Mississippi can have some impact on local elections, but their voices are generally overcome by those of their neighbors. One of the main opportunities they have to express themselves is to donate to prominent politicians in other jurisdictions or join national organizations that they support. Take away their ability to participate in the Tea Party or EMILY’s List, and they may feel completely disenfranchised.

Even conservatives in red states and progressives in blue states may decide to participate in politics elsewhere in the country. With their own ideas being predominant in local elections, they might judge their time and resources to be more effective elsewhere, perhaps in swing states and districts. The bottom line is that voters locally are affected by politics nationwide, so it’s no surprise that political attention is redistributed everywhere.

It’s possible that greater coordination between like-minded voters and groups nationwide contributes to political polarization, but it can be no other way in a free and open democracy. The instinct to demonize out-of-state donors – even ideological ones – unnecessarily estranges Americans from each other simply on the basis of their geography. While locally-run elections primarily focus on the interests of residents of a particular area (and indeed, local voters still make the final decision no matter how much money is given or spent), such races can directly impact the policies of the entire country (especially in federal elections). A voter in Massachusetts can look at an election in Alabama and rightfully judge that their own interests are at stake as well.

It’s impractical to think the government can keep out individuals or groups who are motivated to get involved – but the relative power of ideological donors and activists can be reduced by lifting limits on giving to and coordination between parties and their candidates, allowing them to exercise more power over candidate selection.

American politics is divisive enough without questioning whether our fellow citizens even have a right to speak up in elections. We should not fear when others have a voice, but welcome the chance to robustly engage and participate in our democratic system.