At a June 3 hearing, the Senate Judiciary Committee turned its infinite wisdom to the subject of amending the U.S. Constitution to empower Congress and the states to restrict fundraising, spending, and in-kind equivalents (which aren’t defined in the amendment text) made in support of or opposition to candidates for public office. The amendment, formally known as S.J. Res. 19 and originally proposed by Sen. Tom Udall (NM), currently has 43 co-sponsors in the Senate.

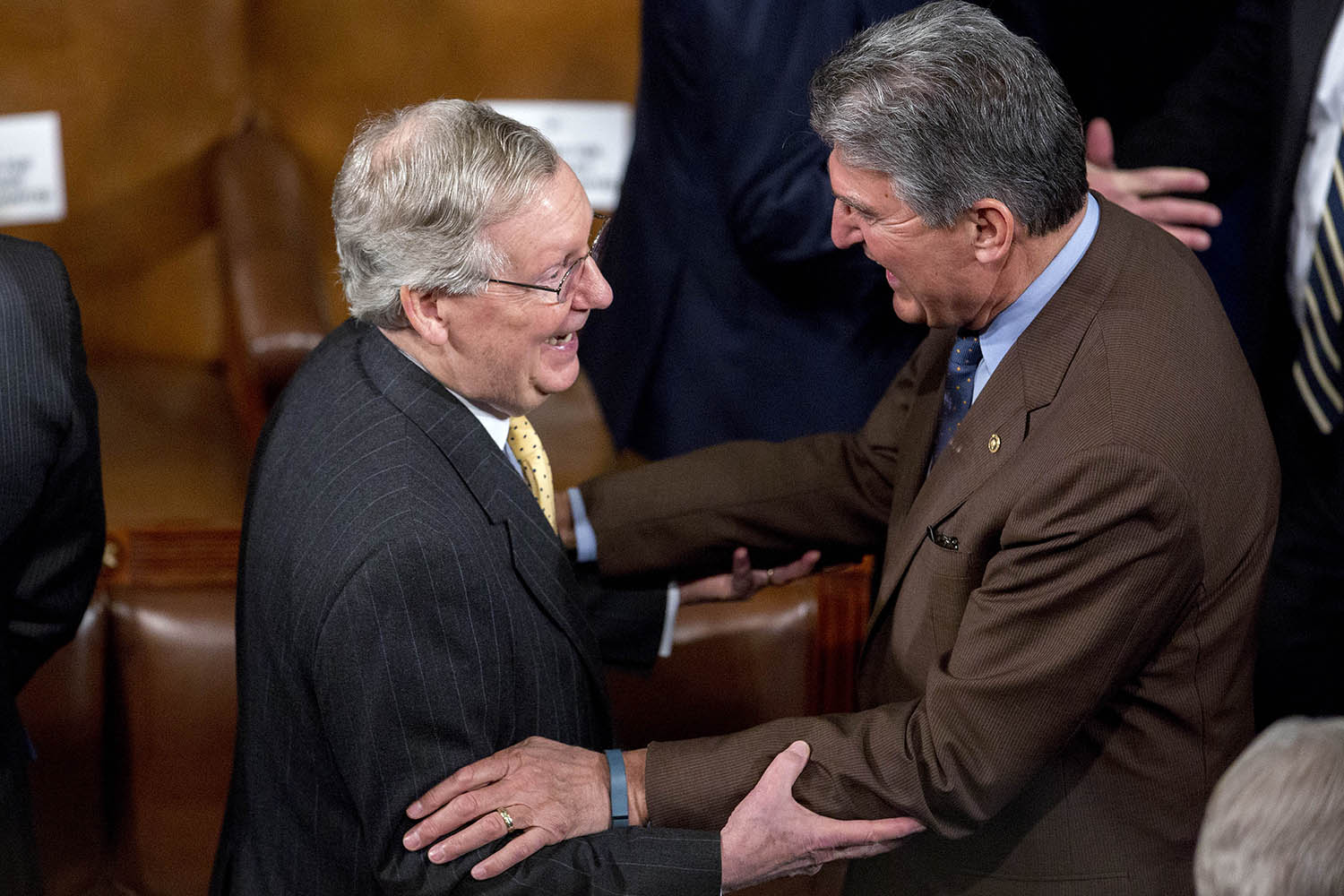

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (NV) and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (KY) made a rare joint appearance before the Committee to offer their thoughts on the Udall amendment, Sen. Reid in support and Sen. McConnell in opposition. After their statements, a panel featuring North Carolina State Senator Floyd McKissick, Jr, famed First Amendment attorney Floyd Abrams, and American University Law Professor and Maryland State Senator Jamie Raskin gave testimony and took questions from the Committee.

McKissick, Jr. focused his testimony on issues affecting North Carolina that he felt were connected to the Citizens United ruling, ranging as far as teacher tenure, Medicaid expansion, and unemployment insurance. In other words, McKissick wants a constitutional amendment to prevent people in power from implementing policies he doesn’t like. Raskin argued that a century-old wall between democracy and plutocracy was being eroded by a “free market” ideology equating money with speech. He won the prize for most hyperbolic on the panel, accusing the Supreme Court of having “bulldozed” the campaign finance system and warning of momentum to “strike down all campaign finance laws.” Abrams took a far different position, noting that the Udall amendment’s intention was to limit speech, which fundamentally contradicts the purpose of the First Amendment, and that it would reverse not only Citizens United and McCutcheon, but also the 1976 landmark campaign finance ruling, Buckley v. Valeo. While McKissick and Raskin thought the 2012 elections were proof that the Court’s rulings had done serious damage to democracy, Abrams contended they were proof that the system worked: more money was spent, enabling more people to speak.

Members of the Committee went back and forth debating whether the Udall amendment was a necessary response to recent Supreme Court rulings or a dangerous attempt to reduce First Amendment rights and expand government power. Sen. Schumer (NY) again compared limiting political speech to noise ordinances, libel laws, and child pornography laws, showing off his profound ignorance of free speech. I’ve written about Sen. Schumer’s inability to distinguish between free speech exceptions – such as noise ordinances, libel laws, and true threats – and restrictions, such as telling a citizen “you’ve spent enough on speech this election cycle,” before. It’s troubling, to say the least, that a senior U.S. Senator doesn’t get the difference.

CCP President David Keating submitted a statement to the committee that can be read here. It says, in part, “If adopted, Senator Udall’s constitutional amendment would help entrench those in Congress by insulating incumbent politicians from criticism and granting members of Congress unprecedented power to regulate the speech of those they serve.”

CCP also performed a legal analysis of the Udall amendment, available here. It concludes, “The Udall amendment would rebuke four decades of campaign finance jurisprudence from the Supreme Court and greatly reduce the quantity of debate in this country. The amendment could be read as a broad grant to Congress to regulate virtually all political speech and association, and fundamentally miscomprehends the free press clause. It is a rhetorical document, introduced during an election year, which highlights the difficulty in tampering with the First Amendment.”

In addition to our legal analysis, CCP looked at how some Senators “evolved” their views on the First Amendment since opposing efforts to amend the constitution to ban desecration of the U.S. flag in the 1990s and 2000s. We discovered that 22 of the Udall amendment’s 43 co-sponsors cast votes on flag desecration amendments, 15 voted no, and at least 8 current Senators took to the House or Senate floor to argue against the flag burning amendments on a variety of pro-First Amendment grounds. Our report collects pro-free speech quotes from current Udall amendment co-sponsors made during the flag desecration debates that suggest a declining reverence for the Bill of Rights among those members. That report can be found here.

Whatever its intentions, the Udall amendment would give government the power to limit a tremendous amount of political activity that is currently protected under the First Amendment. It’s hard to see how limiting political speech could ever help democracy, much less “save” it as the sponsors of the amendment purport. More likely, turning down the volume on campaign speech will serve to satisfy incumbent politicians’ desire to quiet criticism and amplify their own voices above those of the citizens they serve.

For more information, all of CCP’s resources on the Udall amendment are available on this page. We will continue to track and educate the public on efforts to amend the First Amendment and increase government power over election campaigns. As Chief Justice John Roberts wisely wrote in the McCutcheon decision, “those who govern should be the last people to help decide who should govern.”