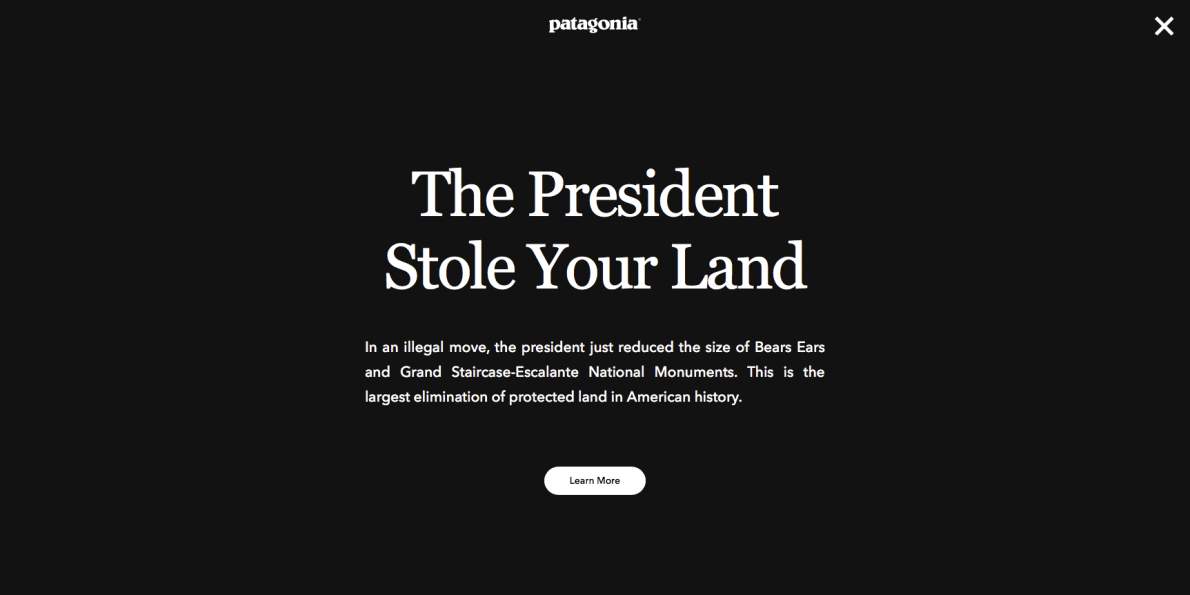

Holiday shoppers visiting the online home of outdoor apparel and equipment retailer Patagonia, Inc. are encountering an overtly political message: “The President Stole Your Land.”

That is just the beginning of the company’s advocacy. Upon clicking “Learn More,” visitors are presented with a brief description of what exactly the company is referring to: “In an illegal move, the president just reduced the size of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments. This is the largest elimination of protected land in American history.” The page also includes a large list of environmental advocacy organizations and encourages visitors to “support these groups fighting to protect public lands.”

In addition to links to the websites of these groups, there is a “Take Action Now” button. That page encourages visitors to “tell the Administration that they don’t have the authority to take these lands away from you.” You can then enter your e-mail address and phone number, and let the company know if you would like to receive updates “about protecting public lands.” But that’s not all. Click “View Tweets,” and you are presented with pre-written tweets directed at President Trump, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke, and Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT). Click “Post Tweets,” and you have joined Patagonia as a political activist supporting Utah’s public lands.

Democracy in action!

Secretary Zinke responded with an all-too-common reaction to just this type of organized political advocacy efforts. He derided the company as just another “special interest” that should be ignored. He even mentioned that some of Patagonia’s products are made outside the United States, presumably suggesting that this fact somehow delegitimizes the company’s voice in U.S. political debates.

But Zinke’s statement belies an underlying truth.

Does Patagonia, a profit-seeking corporation, have political interests? Of course. Patagonia’s mission includes much more than simply accumulating wealth. The company has been deeply involved in conservation advocacy for decades and prides itself on these efforts. That a company, whose customers are outdoor recreation enthusiasts, is concerned about the preservation of protected wilderness lands makes perfect sense.

In fact, the company says, “Climbers, hikers, hunters and anglers all agree that public lands are a critical part of our national heritage and these lands belong not just to us, but to future generations.” What do “climbers, hikers, hunters, and anglers” all have in common? Patagonia sells its products to them. The company’s political advocacy is complementary to the interest of its customers, which in turn is good for Patagonia’s bottom line.

To this, one might respond, “Aha! So, Patagonia’s activism is nothing more than an effort to line their pockets and attract new customers!”

Well, yes and no. Yes, this activism is probably good for business. The reaction has been predictably positive from Patagonia’s target market, and some have even pledged to buy Patagonia products in support of the company’s opposition to the Trump administration’s recent actions and encouraged others to do the same. This does not mean, however, that the company does not genuinely care about the issue or should not advocate for its beliefs.

Patagonia, like every other corporation, is comprised of people. Those people have interests that are affected by the actions of the government. Many of Patagonia’s customers share those interests. Many other companies, and the customers of those companies, also share those interests. And many nonprofit advocacy groups, formed, founded, and run by customers and citizens, share those same interests. If all of these people are able to join forces and convince other Americans that they should also care about what the government is doing regarding public lands, then they have a shot at actually affecting the government’s actions. That really is the democratic process at work.

Criticism of corporate political advocacy is often dismissed, just as Zinke did in this case, because corporate advocacy is driven in part by profit motive. But it doesn’t really matter whether this advocacy can be characterized as altruistic or not.

To insist that all political advocacy should be completely removed from the interests of the speaker is not only unrealistic but, in practice, would be deeply harmful to meaningful and productive political debate. The people and businesses who are most directly affected by specific policies or government actions should be those speaking about those policies or actions.

Of course, it’s possible that the efforts of these concerned citizens will not be effective. Maybe, after all the time and money devoted to advocacy and litigation, the Trump administration moves forward with its decision exactly as it planned. But Patagonia’s speech has still entered the public sphere and been heard by voters. If the company’s speech convinces enough voters to think it’s important, then those politicians who agree with the Trump administration’s stance on public lands will be removed from their positions when the next election rolls around.

To suggest that Patagonia or any other corporation shouldn’t be allowed to legally spend money to advocate on behalf of its employees, customers, and ideological allies simply because it turns a profit or has unique interests is wholly inconsistent with First Amendment principles.

The First Amendment protects Patagonia’s right to keep this ad, or a similar ad in opposition to Trump, on its website every day up until Election Day 2020. The company can thank the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision for safeguarding that right.

The next time you hear someone lament Citizens United as “democracy destroying,” consider the consequences of a ruling in the opposite direction: The federal government would have the power to ban this exact activity from occurring too close to an election with Trump’s name on the ballot.

Organized civic engagement from economic actors should be welcomed in a free and open society. Robust political debate from a variety of speakers is a hallmark of healthy democracy. The moment government possesses the power to censor political speech based on its source, a true threat to democracy exists.