The Democratic and Republican National Conventions have ended, and attention has shifted to the general election season ahead. Yet the parties’ respective platforms endure as a landmark of where they (or at least their most active supporters) stand on the issues at this particular moment in time.

It is no surprise that political speech rights are among the many topics with an evident partisan gap. Democrats all but made their zeal for greater government regulation of political speech the centerpiece of their convention. Both Secretary Clinton and Senator Sanders advocated for overturning Citizens United in their convention speeches, and the Democratic Party platform calls for new rules requiring groups to publicly report their donors and ban independent spending groups. Theirs is a sweeping platform advocating for specific new speech regulations through several channels of government.

The Republican plank on campaign finance is shorter, and the two parties do stand on opposite sides on a few key issues. The GOP advocates for rolling back existing federal regulations on contribution limits, disclosure, and what activities political parties may undertake in support of their candidates. It embraces protections for the political speech rights of businesses, unions, and independent groups.

In short, it appears that the two platforms are substantially different. One party says “Big money is drowning out the voices of everyday Americans” while the other says “Freedom of speech includes the right to devote resources to whatever cause or candidate one supports.” But comparing each platform this year with those from 2012 provides another perspective.

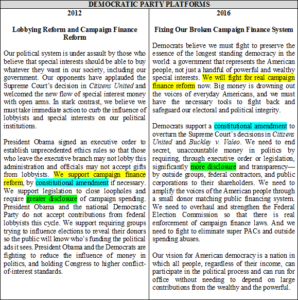

In doing so, it is easy to see how dramatic the Democrats’ newfound embrace of political speech regulations is. That section went from two paragraphs in 2012 to three this year, while total references to Citizens United went from one to three (all of those mentions appear in separate sections of the platform). The Party’s 2012 platform expressed broad, nonspecific support for campaign finance reform and “greater disclosure of campaign spending.” Most references to specific policy simply restate actions that had already been taken: President Obama’s Executive Order on ethics rules for lobbyists, and the national Democratic Party’s refusal of contributions from federal lobbyists (a policy that has since been rescinded). That platform also hedged its speech regulatory ambitions by saying it would support a constitutional amendment “if necessary.”

The Democrats’ 2016 platform elevates the issue to another level. With completely new language, it has called for a more pointed and comprehensive strategy to implement further regulation of political speech on all fronts: legislation and executive actions to significantly increase reporting of giving to citizen groups and giving by federal contractors to trade associations; reporting of donations by businesses to advocacy nonprofits and trade associations to shareholders; taxpayer financing of campaigns; increasing the regulatory power of the FEC by refashioning the agency in a non-bipartisan manner; and unequivocally supporting a constitutional amendment to overturn both Citizens United and the 40-year-old landmark Supreme Court decision, Buckley v. Valeo (although Secretary Clinton hedged on this point, as the Party’s platform did in 2012, in her 2016 convention speech). This evolution over the course of a single election cycle has been dramatic, even though in practice the DNC has become more comfortable courting significant donors this cycle than during President Obama’s re-election campaign.

By contrast, the Republican platform did not see nearly that level of change. This year’s plank on campaign finance did increase from one to two paragraphs, but much of the 2012 wording is unchanged or deleted. Indeed, the first three sentences are nearly identical for each year. Both platforms discuss raising or removing contribution limits, preventing regulation of political speech on the Internet, and even opposing the Fairness Doctrine (a policy that was ended in the 1980s).

Yet 2012’s platform was even more specific than this year’s. It called for a complete overturn of McCain-Feingold, rather than just one element of it; it specifically opposed efforts to undermine Citizens United or Wisconsin Right to Life v. FEC, while the 2016 platform did not mention any Supreme Court decisions; and, in 2012, it closed by strongly arguing against “political correctness” on college campuses in its various forms, which was not mentioned this year. Such an omission is perhaps surprising, given that the opposition to dissenting political viewpoints on college campuses has become far more prominent since 2012, and as Donald Trump has been billed as an anti-PC candidate.

Indeed, the only political speech issues on which the 2016 GOP platform is more specific are protecting the political speech rights of advocacy groups, corporations, and unions and opposing mandatory political contributions via union dues.

While the two platforms definitively draw a contrast on campaign finance issues in 2016, it does not mean that both parties are shifting strongly to their respective extremes. Only the Democrats have billed themselves as the party that not only wants to fully embrace these issues, but is willing to take even more regulatory steps than before.

The platforms of both parties from 2012 and 2016 can be viewed below, with repeated language from each year highlighted. The Democratic Party’s 2012 platform can be viewed in full here while its 2016 platform can be viewed in its entirety here. The Republican Party’s 2012 platform can be viewed in full here, and its 2016 platform can be viewed in totality here.