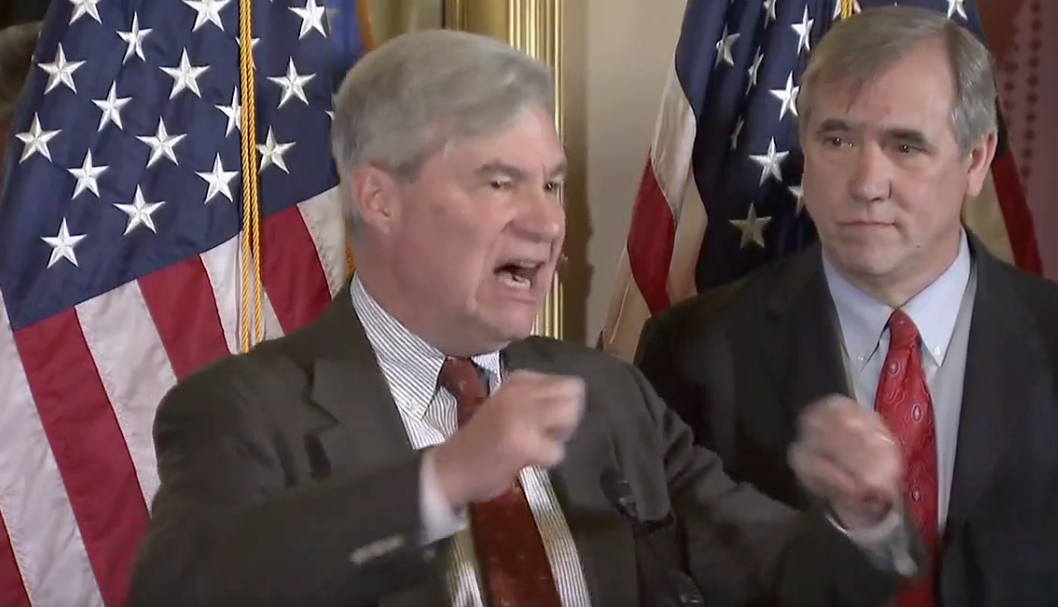

Last week, Senate Democrats introduced their companion bill to the House’s recently passed H.R. 1, also known misleadingly as the “For the People Act.” The press conference held by the bill’s lead sponsors was quite the spectacle. From Senator Sheldon Whitehouse describing Americans who choose to associate privately as “cockroaches” to Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer referring to advocacy groups as “evil forces,” it was a grand display of hyperbolic fearmongering and ahistorical nonsense.

Senator Tom Udall opened up the press conference by declaring that “our democracy is at a crisis point” and “the system is rigged.” This sort of democracy-is-dead rhetoric is typical of powerful politicians pushing for ever greater regulation of speech about themselves. (And Tom Udall is certainly one of those politicians.) When members of Congress are attempting to convince Americans that Congress should have more power to restrict and regulate core First Amendment activity, fear is often the rhetorical tool of choice. The suggestion that American democracy will literally crumble unless you give politicians this power is a pretty compelling argument. But Americans shouldn’t fall for such fearmongering.

The “evil forces” these Senators are talking about are nothing more than groups of Americans pooling their resources to speak about candidates and policy issues. Unlike these Senators, these groups have no real power. All they can do is attempt to convince other Americans of the merits of their arguments.

Senator Whitehouse contends that these groups possess immense power because they can “threaten and promise to spend unlimited money” on negative speech about members of Congress. But why is that “corrosive of democracy,” as he puts it? Political speech is only effective so far as voters agree with it, disagree with it, or are concerned with what the speech brings to light. And “threats” of political speech only impact members of Congress if they know their constituents will have a negative response. Using one of Mr. Whitehouse’s favorite boogeymen as an example, a trade association representing the interests of fossil fuel companies could spend millions of dollars telling Senator Whitehouse’s constituents that he voted for stringent environmental regulations that will lead to massive job cuts in the fossil fuel industry. But his supporters and detractors alike know he passionately supports such regulation, so the ads would likely have little to no effect. Similar ads run against a Senator from West Virginia might be more effective. Regardless, the fact that groups hold members of Congress accountable for their actions while in power is far from “corrosive of democracy.” It strengthens democracy.

As we’ve seen time and again, money can buy neither electoral nor legislative outcomes. No amount of political spending could convince a majority of Alabamians to vote for Hillary Clinton in 2016. And no amount of negative ads could convince a congresswoman representing a deep blue district in New York City to vote against a gun control bill she and her constituents support. The idea that money spent on political speech is an all-powerful, controlling force in American politics amounts to little more than a conspiracy theory.

Now to the ahistorical nonsense. After railing against those who dare speak about powerful politicians as “people of malign influence,” Senator Schumer said this:

“This idea that the First Amendment means that a multibillionaire can put as much money into our political system as anyone else had nothing to do with the First Amendment until these right-wing think tanks thought that up, and unfortunately, a Supreme Court that’s become much more political went along.”

Besides the fact that Schumer’s poor phrasing seems to bemoan that wealthy people have the same rights “as anyone else,” his characterization of First Amendment jurisprudence related to campaign finance law is grossly inaccurate.

The first major First Amendment challenge to modern campaign finance law was brought by plaintiffs from across the political spectrum. And the “idea” that campaign finance regulations implicate First Amendment rights is far from a right-wing invention.

In 1974, Congress passed amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) imposing, among other things, limits on the amounts that candidates and groups could spend on campaign speech. Plaintiffs, including the New York Civil Liberties Union and former Democratic presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy, challenged these limits under the First Amendment.

In 1976, the Supreme Court struck down all of FECA’s spending limits, writing, “The concept that government may restrict the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voices of others is wholly foreign to the First Amendment.”

In 2010, with amicus support from such “right-wing think tanks” as the American Civil Liberties Union and The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, the conservative nonprofit Citizens United successfully challenged portions of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA). BCRA banned nonprofits, businesses, labor unions, and other associations from making “electioneering communications,” defined as “any broadcast, cable, or satellite communication” that mentions a candidate within 60 days of a general election or 30 days before a primary election. The Supreme Court struck down this ban, as well as the ban on such groups expressly advocating for or against candidates, as unconstitutional under the First Amendment.

Prior to the Citizens United case, EMILY’s List, a group that advocates for the election of Democratic women who support abortion rights, successfully challenged limits on spending by nonprofit groups in the D.C. Circuit.

All of this is to say that the First Amendment right of individuals and groups to spend unlimited money on political speech has been supported by free speech advocates and upheld by jurists across the political spectrum.

And while every Democrat in Congress may support the speech restrictions included in the “For the People Act,” it is not only groups on the right that have expressed First Amendment concerns with the bill.

Throughout the press conference, the Senators made clear that they want to make it “easier, not harder” for Americans to exercise their right to vote. If only they felt the same way about Americans exercising their right to speak.