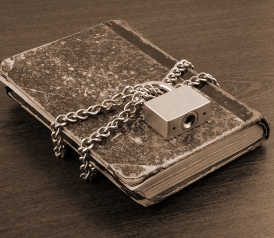

The Federal Election Commission’s recent public meeting revealed a partisan gap on what would have otherwise seemed a straightforward issue. Commissioner Lee Goodman proposed an amendment to expand the FEC’s “press exemption” regulation to include books, movies, and other media distributed by satellite television, radio, and internet-enabled applications. In short, Goodman wanted to reassure the public that the federal government wouldn’t be banning books or censoring documentaries anytime soon.

This provision failed in a 3-3 vote along party lines, with the Democratic commissioners signaling that they were unprepared to rule out such regulation.

Importantly, Commissioner Goodman’s proposal would not have created new law – rather, it would have clarified the scope of the already-existing press exemption, which spares media organizations from being subjected to campaign finance regulations for their speech. In practice, this means that newspapers like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal may endorse or criticize a candidate without the FEC stepping in.

The amendment proposed by Commissioner Goodman would have simply filled some of the gaps in the existing press exemption by acknowledging the obvious fact that freedom of the press encompasses more than just newspapers – it includes books and documentaries, whether distributed by electronic or more traditional means. The surprising failure of this amendment is significant in two major ways.

First, it highlights how proponents of greater speech restrictions are hoping to leave the door open for federal agencies to regulate the internet and other technologies in ways that would be unthinkable for traditional media. Rather than seeing the internet as a bastion of free speech, some on the FEC see it as a nuisance.

Commissioner Ann Ravel is particularly notorious for her crusade to regulate internet speech. This amendment vote came in the wake of her comments earlier in the week decrying “microtargeting” by online content creators, a practice she believes is “exclusionary” and allows political ads to ignore minorities. Of course, targeting different consumer bases is something that all advertisers, including political ad makers, have done for many years, and the federal government cannot reasonably expect to regulate such a practice, but the fact that this targeting is occurring on the internet seems to be reason enough for Ravel to attempt to further regulate speech.

By leaving the FEC’s regulatory policy on the press exemption excessively narrow, it may also be that some commissioners are hoping to preemptively chill political expression and reserve the right to create new speech restrictions in the future. Over the summer, Commissioner Ravel revealed her thought process in this regard when she claimed it was not her job to “apply constitutional principles” to her policy decisions, signaling that it is perhaps better to regulate at will, push the limits of regulatory policy, and let the courts sort everything out afterwards.

Second, this episode illustrates how regulations have a tendency to drift in a far more restrictive direction unless actively checked. Recall that officials from the Obama Administration famously admitted before the Supreme Court that federal law would have allowed the government to ban books that engaged in even minimal political speech – that is, before the Citizens United decision struck down such provisions. Some pro-regulation voices might have felt a modicum of relief that they were past the embarrassing episode of being on the record in favor of banning books.

However, the FEC’s failure to clearly state that it will protect internet-enabled speech means that this criticism cannot yet be put to rest. Until the FEC agrees to expand its press exemption beyond CNN and The New York Times, it is valid to ask how increased regulation won’t lead to abuses like book-banning.

No, there aren’t currently any specific books the FEC hopes to regulate – but at least three commissioners still want to keep that door open, just in case some book (or similar media publication) might strike them (or future regulators) as unacceptable in the future. The disturbing fact that this is even an open question allows the public a rare, unfiltered glimpse into the mentality of those who wish to further regulate citizens’ political speech.