Report Overview

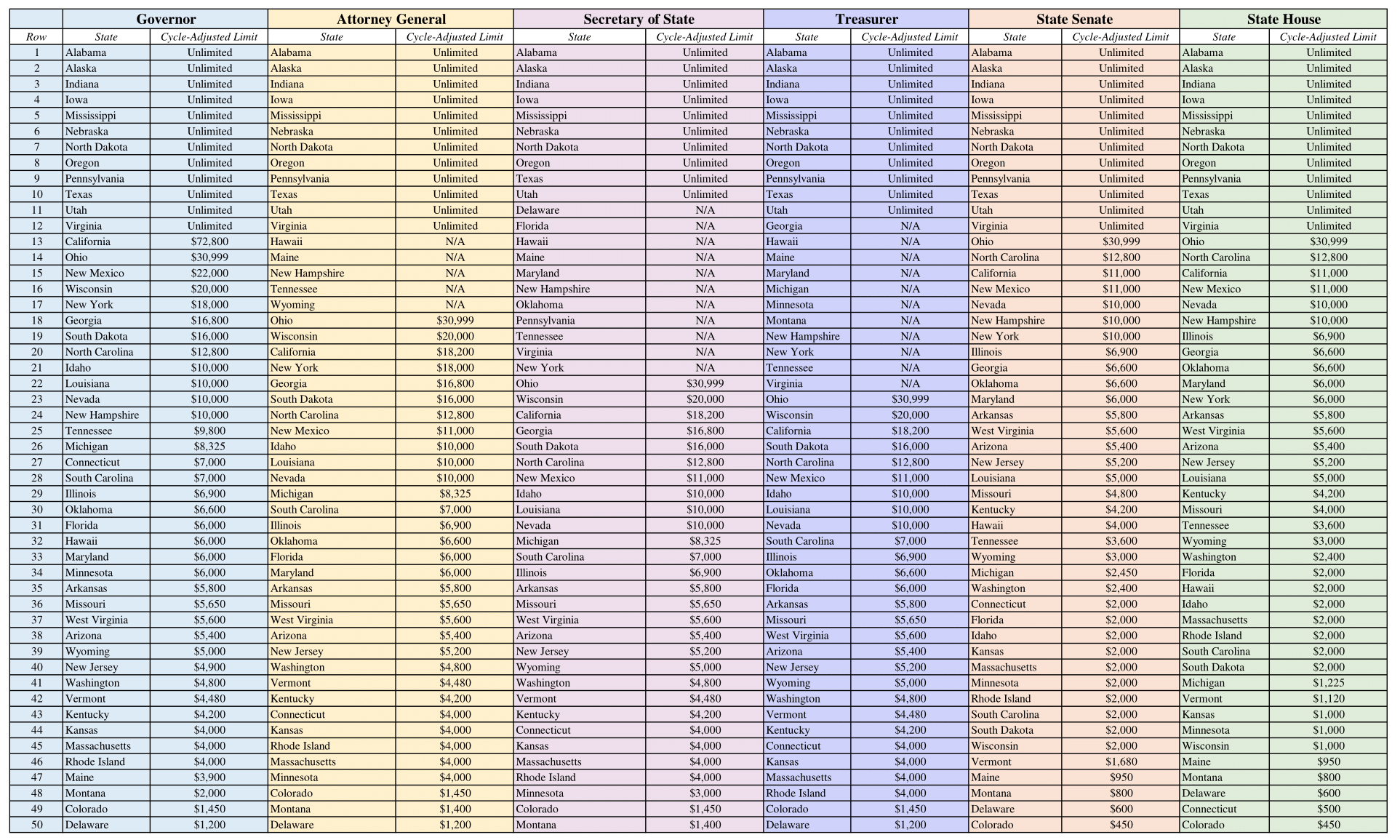

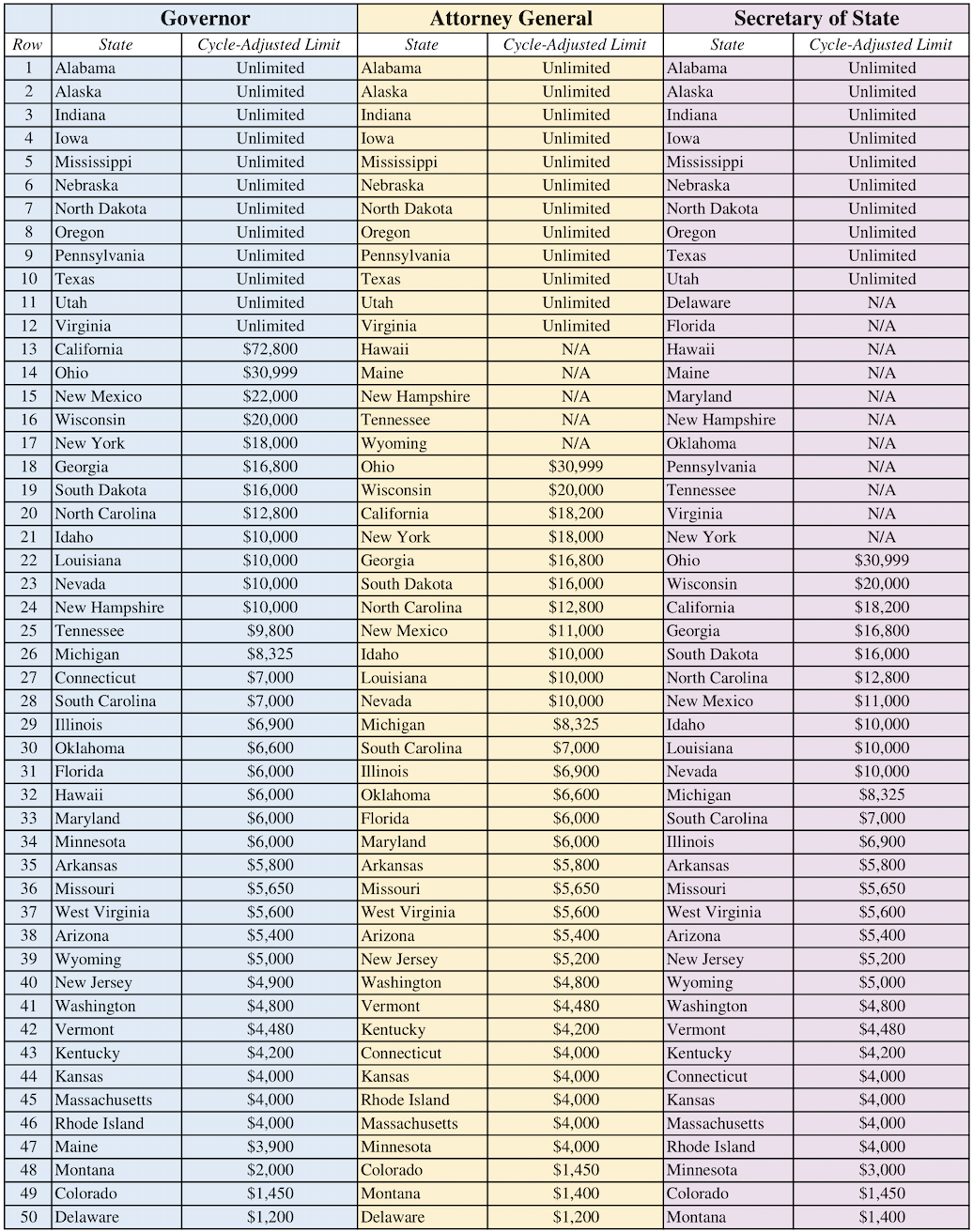

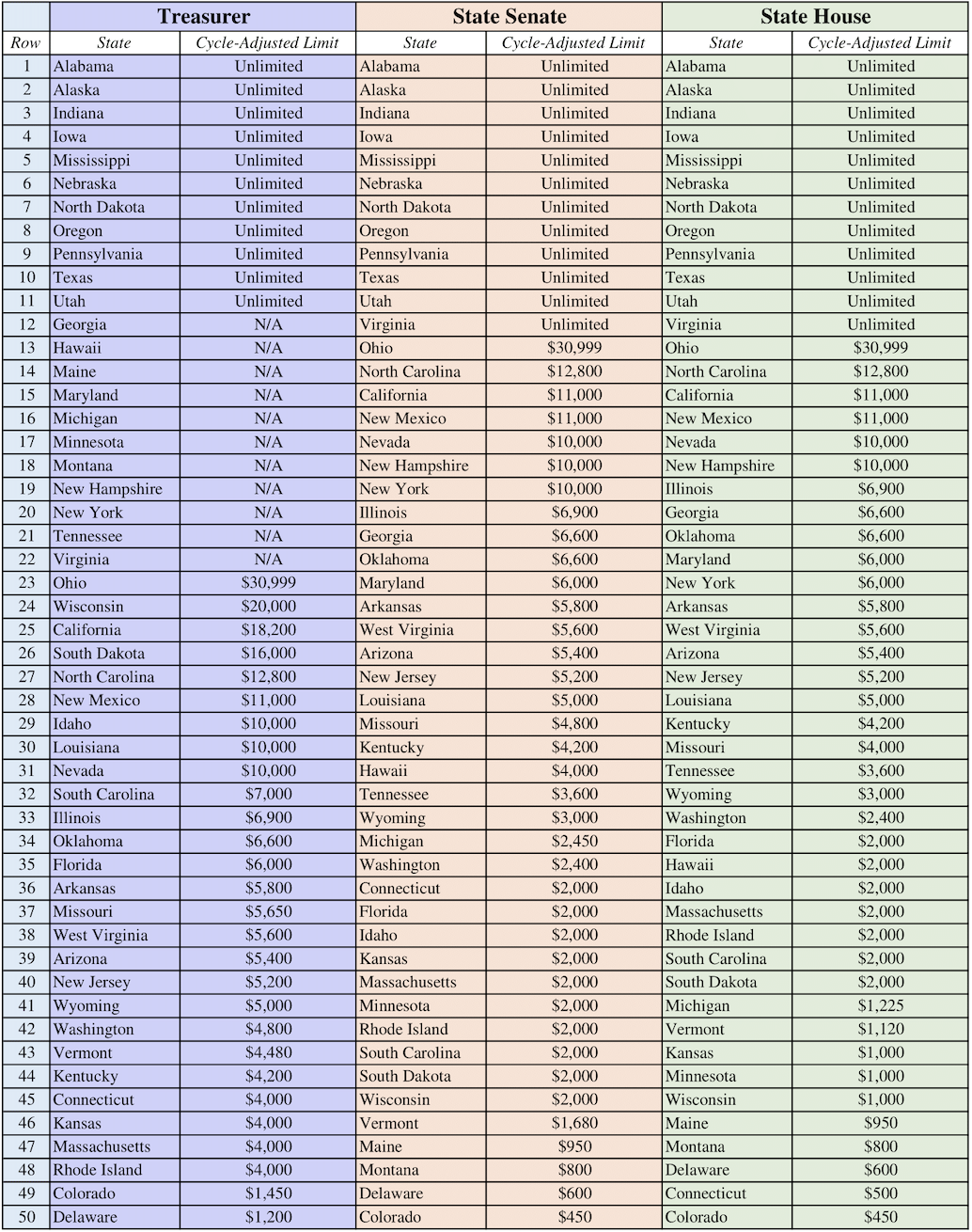

This comprehensive report examines the limits that all 50 states place on individual contributions to campaigns for major elected offices. The report details the various limits states impose on political giving for individuals and offers a link to state information and the statutory language on the limits.

The second part of the report ranks the states from best to worst in terms of the freedom of individuals to support the candidates of their choice, thereby enabling the reader to easily see which states have the most and least restrictive contribution limits.[1]

Imposing contribution limits is by no means a universal practice, and limits are not tied to the general partisan political makeup of states. For example, the twelve states that allow for unlimited campaign contributions include states like Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Oregon as well as states such as Iowa, Indiana, and Texas.

The chart in this report shows that speech is significantly more burdened in some states than in others. Take Colorado, for example, which imposes an extremely restrictive limit of $225 for state senate campaigns. By contrast, in neighboring Utah, a person can make unlimited contributions to state senate races, and in New Mexico the limit is $5,500 (about 25 times greater than the limit imposed by Colorado). Colorado also has the ignominious distinction of having the lowest individual contribution limits for state legislative races in the country.

The complexity of contribution limits is even greater because some states follow a patchwork style, with different limits for different elected offices within the state. For example, in Vermont the limit is $4,480 for gubernatorial races, $1,680 for state senate races, and $1,120 for state house races. A citizen contributing to different races must keep track of these various limits across races to avoid running afoul of the law. By contrast, New Hampshire imposes an individual contribution limit of $5,000 across the board for all state campaigns. Virginia imposes no individual limit at all. Simple regulatory models like these have less of a chilling effect on political giving.

Why Do Campaign Contribution Limits Matter?

In our system of government, the ability to speak about candidates for public office is perhaps second only to voting in its ability to effect change. But in a country with a population over 330 million, speech is not particularly effective when shouted from a street corner. To reach a significant number of voters, speakers need the ability to amplify their voices by forming associations and pooling resources. Modern campaigns rely on television, radio, online advertising, newspapers, rallies, mailings, canvassers, and coordinating volunteers. All these efforts cost significant amounts of money.

For the First Amendment’s protection of expressive freedom to be meaningful, its coverage must extend to the means of making and disseminating speech as well as the speech itself. Indeed, for those who do not own their own media outlet or have the time to volunteer for a campaign, making monetary contributions to candidates offers perhaps the best and most efficient way to give voice to their political views.

The ability to make contributions to candidates and groups facilitates political speech, and protecting political speech is a core component of the First Amendment. As the U.S. Supreme Court explained in Buckley v. Valeo, “Making a contribution, like joining a political party, serves to affiliate a person with a candidate. In addition, it enables like-minded persons to pool their resources in furtherance of common political goals.” While the Court upheld contribution limits, it did note that “contribution restrictions could have a severe impact on political dialogue if the limitations prevented candidates and political committees from amassing the resources necessary for effective advocacy.” But it concluded that there was “no indication…that the contribution limitations imposed by the Act would have any dramatic adverse effect on the funding of campaigns and political associations.”

Later, in Randall v. Sorrell, the Court struck down Vermont’s contribution limits for being too low. The Court held that “contribution limits that are too low can. . . harm the electoral process by preventing challengers from mounting effective campaigns against incumbent officeholders, thereby reducing democratic accountability.”

Contribution Limits and Equality

Contribution limits have real world consequences, restricting the speech of some, and, in effect, enhancing the speech of others. First, consider that incumbents enjoy significant benefits – such as name recognition, free media coverage of their political activities, free mailing privileges in some circumstances, access to extensive donor databases from previous campaigns, and political networks. Having used money over time to build their advantages, contribution limits make it more difficult for challengers (and their supporters) to express different political views.

Challengers have a greater need for larger contributions early in a campaign where they have smaller political networks and less name recognition. By capping what supportive donors can give to a campaign, contribution limits prevent challengers from amassing the funding they need in order to wage a competitive election against entrenched incumbents.

The relative influence of political speech can also never become equal. The current system gives tremendous advantages to media corporations, social media platforms, search engines, influencers on social media platforms, and celebrities. Their endorsements, or the manipulation of speech that is served to users, are often worth far more than the even most generous contribution limit.

The Supreme Court has, properly in our view, found it unconstitutional to limit contributions to and expenditures from independent groups. Thus, instead of funneling money to candidates who are directly responsible and attributable for their speech, contribution limits have created an odd system where independent speakers such as Super PACs can sometimes have more messaging power than the campaigns they support or oppose. Higher contribution limits would enable individuals to directly support a candidate’s message.

Contribution Limits and Corruption

In Buckley, the Supreme Court ruled that preventing quid pro quo corruption, and the appearance of such corruption, are the primary legitimate interests that government has when imposing campaign contribution limits.

As a previous Institute for Free Speech report found: “Almost no states that rank highly for free political expression are highly ranked states for corruption. In fact, states that have the most robust free expression protections outperform the national average for per capita rates of corruption.”[2] Public corruption prosecutions can also serve as a proxy for corruption, and evidence from the Department of Justice shows that public corruption charges have steadily declined in the ten years since 2010.[3] The Institute also conducted an analysis of whether contribution limits produce better governance, and found that there is no “reason to believe that low limits on what citizens can give to candidates for public office has any effect on how well a state will be governed.”[4]

Additionally, campaign contribution limits are not strongly linked to perceptions of corruption. A study by political scientists Daron Shaw, Brian Roberts, and Mijeong Baek found that “voters in jurisdictions that regulate campaign finance more aggressively do not necessarily perceive less corruption than do voters in jurisdictions with relatively less regulation.”[5] They also found that “increased average spending in federal elections has virtually no impact on perceived corruption.”[6]

Perceived corruption should also be strongly linked to trust in government. After all, it makes little sense for you to trust your government if you believe it is corrupt. However, as political scientist David Primo and economist Jeffrey Milyo found, after conducting a vast study of trust in government relying on 50 survey results over a 30-year period, there are “no statistically or substantively significant positive effects of campaign finance reforms on trust in government.”[7]

Contribution limits can also help protect the corrupt. When contribution limits are low, it requires the participation of more citizens to get the word out about corrupt behavior or the need for a change. But taking on a corrupt politician is something not many Americans are willing to do, because the cost of failure is often high. As the old saying goes, “When you strike at a king, you must kill him.”

Low limits make it both harder and riskier to take on a corrupt politician. Meanwhile, those same corrupt politicians often try to ward off charges of corruption by demanding new laws restricting campaign speech. They benefit twice. First by the usually favorable media coverage they get for calling for limits on “money in politics.” Then a second time when new speech restrictions make it harder to expose their corruption.

Recommendations

- States that retain individual contribution limits should make them easy to follow and provide information about them in easily accessible formats.

- All contribution limits should be indexed to inflation, otherwise inflation will erode contribution limits over time. Many states already adjust for inflation, but many states do not. For those interested in determining whether their state adjusts contribution limits to inflation, and for those wishing to learn about correct inflation adjustment practices, see the Institute for Free Speech’s Report on Inflation Adjustments to State Contribution Limits.[8]

- States with low contribution limits should strongly consider raising or eliminating the limits. First Amendment principles reject the notion that government should decide who speaks, how much they speak, and with whom they speak. Yet contribution limits do just that, imposing direct restrictions on the ability of citizens to associate with each other and with candidates, reducing their collective ability to speak. And when candidates and causes cannot raise the funds needed to reach a large audience, it is not only the would-be contributors, but also the would-be listeners who are deprived of the benefits of the First Amendment.

Cycle-Adjusted Methodology

- For states with per- election cycle limits, the limit was taken

- For states with per election limit, the limit was doubled to account for the primary and the general (run-off elections were not included)

- For states with yearly limits, the limit was adjusted for the length of the term of office (i.e. a yearly limit for a four-year gubernatorial office was quadrupled, a yearly limit for a 2-year state representative was doubled)

[1] If two or more states impose identical limits, then the states are listed alphabetically.

[2] Alec Greven, “Do States with Fewer Campaign Finance Regulations Have More Corruption?,” Institute For Free Speech, May 24, 2023, https://www.ifs.org/research/do-states-with-fewer-campaign-finance-regulations-have-more-corruption/.

[3] Alec Greven, “Has Citizens United Increased Corruption? An Examination of Public Corruption Prosecutions,” Institute For Free Speech, September 3, 2020, https://www.ifs.org/research/citizens-united-corruption/.

[4] Joe Albanese, “Updated: Do Lower Contribution Limits Produce ‘Good’ Government?,” Institute For Free Speech, October 1, 2013, https://www.ifs.org/research/issue-analysis-6-do-lower-contribution-limits-produce-good-government/.

[5] Daron Shaw, Brian Roberts, and Mijeong Baek, The Appearance of Corruption: Testing the Supreme Court’s Assumptions about Campaign Finance Reform (Oxford University Press, 2021), 46.

[6] Ibid., 69.

[7]David Primo and Jeffrey Milyo, Campaign Finance and American Democracy: What the Public Really Thinks and Why It Matters (University of Chicago Press, 2020), 145.

[8] Alec Greven, “Report on Inflation Adjustments to State Contribution Limits,” Institute For Free Speech, September 19, 2023, https://www.ifs.org/research/report-on-inflation-adjustments-to-state-contribution-limits/.