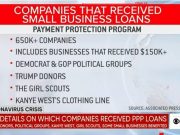

The $3 trillion annual federal budget contains $460 billion in grants and $340 million in contracts, but there is no simple way for the public, the media, or even lawmakers to discover exactly where this money is being spent, complained Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.). Coburn sponsored the new disclosure legislation [S. 2590] and chaired the hearing of a Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs subcommittee on the bill.

– Kenneth P. Doyle, “Transparency in Federal Funding Touted in Battle Against ‘Earmarks’” BNA, Money & Politics Report, July 19, 2006.

With all the discussion of disclosure—from disclosure of campaign contributions, to disclosure of independent expenditures, reporting by ballot initiative committees, funding of 527 organizations, lobbying disclosure, grassroots lobbying disclosure and now earmark disclosure— and with some of it coming from CCP, we thought it important to sketch guidelines as to which disclosure is legitimate and which is infringing.

Much work has been done recently on the upper and infringing limits of disclosure, with a lot of it noting that the very sunlight that disinfects the operations of lawmakers and implementers can cause sunburn to citizens and civic organizations when applied in improperly to the private sector; when applied improperly to groups rightly fearful of retribution and jealous of their anonymity. Different advocates draw the line differently. To CCP, disclosure serves always to expose abusive officeholders, and is proper where there is a nexus to officeholders, or where disclosure casts an eye on the operations of lawmakers, as lawmakers, or the executive.

Campaign contributions and lobbying disclosure fit the bill, even as the data created by such disclosure too often recasts news stories away from the merits of policy issues and legislative proposals and into stories of political leverage and influence; into stories of who wants what, and ignoring whether the ‘what’ is good or bad. Public officials have freewill, can be persuaded and corrupted, and are, as Weber put it, the legitimate monopoly on the use of physical force. Citizens have a right to know who is directly influencing their officeholders.

Ballot initiative campaigns and “grassroots lobbying”—which are little more than citizens persuading fellow citizens on the relative merits of competing, yet fixed and knowable, policy prescriptions—however, seem less like areas where sunlight can to lead to anything but citizen sunburn. Both lack any meaningful link to officeholders, making quid pro quo corruption or its appearance impossible.

Something is amiss in the “informational” interest discussed in the ballot initiative disclosure case of California Pro-Life Council, Inc. v. Getman, 328 F.3d 1088 (9th Cir. 2003), and what that court there intimates is a need to preserve the “integrity of the ballot-initiative process.” Id. at 1103. Ballot initiative disclosure does not serve to “place … candidate[s] in the political spectrum,” Getman at 1105; it merely places issues in the political spectrum. But issues do not have free will and cannot stray or become corrupted; they are ascertainable on their face and knowable in detail with a little bit of added research. Ballot initiatives and grassroots lobbying do not corrupt officeholders and by extension do not corrupt the legislative process, a core concern of the Supreme Court in Buckley. They do not corrupt balloting or the vote tabulation process. When stripped of its grandeur, the informational interest in ballot initiative disclosure is little more than a fig leaf for frustrating a citizen’s right to engage in issue discussion anonymously. And the interest in information on grassroots lobbyists is piqued more often by the very lawmakers disclosure laws should protect us from, rather than by fellow citizens, as CCP has discussed in detail elsewhere.

The disclosure of 527 funding seems proper where it is tied to officeholders; that is, when a 527’s activity is coordinated with an officeholder or her agents and brought with federal campaign finance law. (We are not saying these 527 organizations should or should not be entitled to preferential tax treatment, but are saying that 527 activities independent of officeholders should not be subject to compelled disclosure.)

This leaves Senator Coburn’s proposals for earmark disclosure. BNA reports that the public web site called for in the Coburn bill would:

contain the name of each entity, besides a federal agency, that receives federal funding [and list]: the amount of any federal funds that the entity has received in each of the last 10 fiscal years; an itemized breakdown of each transaction, including funding agency, program source, and a description of the purpose of each funding action; the location of the funded entity and the project involved; and ‘any other relevant information.’

Doyle, supra. As described, the proposal seems valid. It seems to do what disclosure laws are meant to do.

On the map of quid pro quo corruption, appropriators are at ground zero. The people have a say in, and are deserving of information on, the official actions of their representatives, and deserve to hold them accountable for their decisions. It seems the proposal would provide information to citizens rightly interested in the relative merits of competing budgetary proposals in an era of relative scarcity. And casting sunlight on the amounts and recipients of largesse can be disinfecting in numerous ways.

But what about the organizations that have earned their earmarks fair and square; those who have gleaned in a hard fought contest their smidgen of expropriated wealth from their fellow citizens, citizens who’ll scarcely notice the expense in a budget of 3 trillion dollars? Aren’t they entitled to a little sun block? Entitled to a little SPF 45? Hardly.