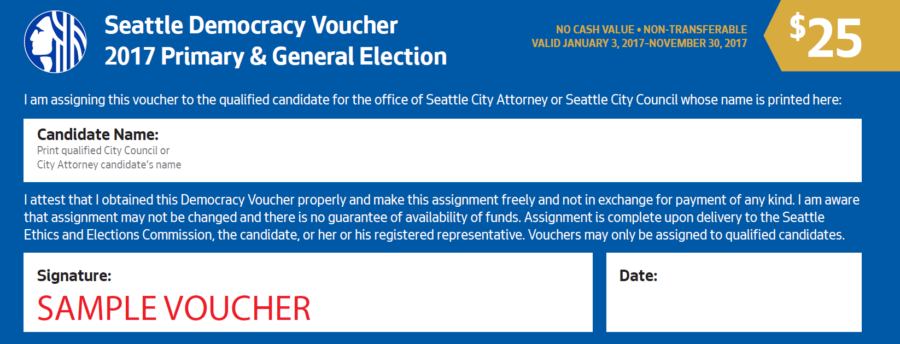

Seattle’s new “democracy vouchers” program is the latest effort by supporters of greater campaign finance regulation to give government a bigger role in political campaigns. The system funnels taxpayer money to politicians via four $25 vouchers for each registered voter, and is intended to reduce candidates’ need to fundraise via voluntary contributions. Some Seattle property owners have challenged the law (with help from the Pacific Legal Foundation) on the grounds that raising their taxes to pay for political speech that they may not agree with is unconstitutional.

One of the politicians benefiting from this system, City Council candidate Jon Grant, says this is just fine:

“The last time I ran,” says Grant, a community activist who unsuccessfully sought a council seat in 2015, “our campaign was outspent 8 to 1.”

This time he’s the one outspending his opponents.

…

So far, he is one of three candidates who’ve qualified to receive vouchers. (Only council and city attorney candidates can qualify this year; in 2021 the program will include the mayor’s race). Ten others are still seeking qualification and four refused the offer, saying they didn’t need the money or that the tax was unfair.

Grant has raised $201,000 in total contributions, said his aide Erin Fenner, with about 92% of that coming from vouchers.

Teresa Mosqueda, one of Grant’s opponents, has raised about $69,000 in voucher contributions, and incumbent City Atty. Pete Holmes has collected just over $43,000, according to city figures.

Grant is upfront about the fact that his campaign is almost entirely sustained by taxpayer money. This is a happy reversal of fortune for him, having failed to win donors and voters to his cause last time he ran. But his accomplishment shouldn’t be confused for a positive development for the political system as a whole. Frustrating as it might be for candidates to be outspent by an opponent due to an inability to attract voluntary support, this result certainly doesn’t entitle lawmakers to compel taxpayers to contribute to their campaigns. Tax dollars aren’t meant to “level the playing field” for politicians. Candidates for office should have to earn their donations and votes.

Learning to adapt to the existing system might have yielded some benefits to Grant’s campaign apparatus too. After all, taking the time to increase one’s name recognition, establish relationships with potential constituents, and develop a platform that appeals to a broad swath of voters all goes hand-in-hand with the fundraising process. Those are difficult but necessary steps in electoral politics in general. It’s possible that Grant, having run for office unsuccessfully in the past, would have honed these skills with the benefit of experience and become better at fundraising on his own.

Of course, it’s also possible that Grant’s constituency is unwilling or unable to donate to his campaign without being subsidized by “democracy vouchers” – perhaps they lack the financial means to do so or are disenchanted with politics. Even so, that wouldn’t justify forcing taxpayers to participate by redistributing their funds in the form of vouchers. Even if Grant had been outspent a second time in an entirely voluntary system, that wouldn’t necessarily have been a death sentence for his campaign. After all, money doesn’t win elections, votes do.

It is striking how few candidates, aside from Grant, have qualified for vouchers so far, or raised the amount that Grant has through the system. It’s one thing when a fundraising or spending imbalance occurs organically from voluntary contributions – it’s quite another when such imbalances are created by government. The fact that so many other candidates are apparently having difficulty navigating the system could unfairly handicap them, since any delay in qualifying for such vouchers would give their opponents a crucial head start in fundraising and election spending. Participation in the system also requires limits to campaign expenditures that further skew the race.

Grant’s statements are only the latest example of politicians supporting regulations, taxes, and other government actions that benefit themselves while claiming that a particular program or subsidy is in the public’s interest. Grant believes he’s “blazing a new political trail that he hopes other cities follow.” All he’s really doing is normalizing a blatant conflict of interest whereby politicians write the election rules that best suit their ability to win and retain office.