These days, supporters of increased political speech regulation often fixate on topics like super PACs and so-called “dark money” when fear-mongering about the current state of campaign finance regulation in the United States. But occasionally they reveal their discomfort with basically any form of political speech that allows individuals to pool their resources and jointly participate in politics – no matter how heavily-regulated or long-standing those types of speech are. Such is the case with the new “NO PAC Caucus” in Congress.

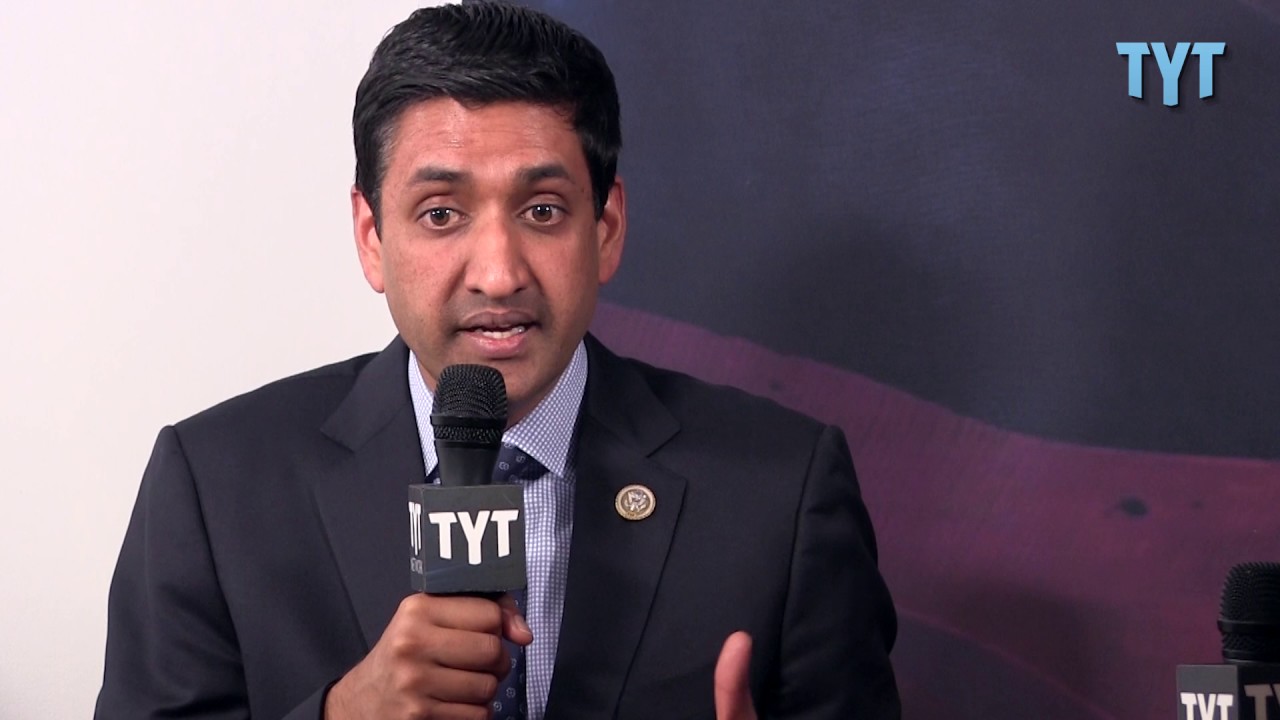

Representative Ro Khanna of California is forming a new caucus for lawmakers who pledge not to accept contributions from PACs or lobbyists. He has also introduced a bill (H.R. 1743) that would ban candidates for U.S. House or Senate from accepting any PAC contributions at all.

This is a deeply flawed crusade. If the concerns of today’s critics of campaign finance law are unlimited contributions or undisclosed donors, PACs should be about the furthest thing from their minds. Political action committees – which have existed for nearly 75 years – are subject to strict reporting and disclosure requirements, and they can give no more than $5,000 to a candidate per federal election (an amount not much higher than the $2,700/election limit for individual giving). Does anybody really think that $5,000 is enough to bribe or decisively influence a lawmaker? Especially considering any lawmaker is likely to receive many times that amount from a multitude of sources?

Nobody with any knowledge of campaign finance law or the First Amendment would ever argue that we could ban contributions from individuals to candidates. So why do PACs get singled out? Individuals have the right to express their opinions via political donations, and they do not forfeit that right by choosing to pool resources with other like-minded individuals. That’s all a PAC is – an organization that donors trust to pursue their common interests.

Of course, Congressman Khanna and his fellow caucus members are free to reject whatever contributions they want. Indeed, if they were to stop there and simply let voters decide whether accepting PAC money is a major issue that will determine who they vote for, it would allow the public to make their feelings clear without infringing on anybody’s First Amendment rights. Unfortunately, as is typical for lovers of regulation, it isn’t sufficient to keep individual decisions voluntary. Instead, Congressman Khanna wants to decide for everyone, through his legislation, who gets to participate in politics.

Swearing off PAC money may seem like a selfless, difficult decision for Khanna, but that is not the case. As Politico notes:

Khanna, who represents much of Silicon Valley, acknowledges that not every member will have an easy time quitting PAC money. Khanna defeated Democratic Rep. Mike Honda last year after raising $3.7 million, including big checks from tech elites including Marc Andreessen, John Doerr, Sean Parker and Laurene Powell Jobs, and [Rep. Jared] Polis [another member of the NO PAC Caucus] is one of the richest members of Congress. “I’m very sympathetic to the argument that members” in less affluent districts “have a harder challenge in fundraising,” Khanna said. “I think we have to be sensitive to that.” “This is not with any judgment on my colleagues [who accept PAC money] or any sense that my position is any more moral than theirs,” Khanna added.

It’s no surprise that Khanna can afford to eschew donations from PACs when he happens to represent an exceptionally wealthy district. Since there are many avenues for political speech, a politician can afford to benefit from some and say that the others are not necessary (the implication being that some voters or interests are worth listening to, while others aren’t). Khanna claims that he is “sensitive” and “sympathetic” to those concerns, but his words ring hollow once you remember that he has introduced legislation that would specifically ban PAC contributions for all congressional candidates. Not only does that violate the First Amendment rights that give all citizens the option to speak out as they see fit, but it also goes against American ideals of localism and federalism that allow policy to adapt to local circumstances.

Those facts are what make Khanna’s proposals so harmful. Maybe it’s out of genuine lack of understanding about what campaigns look like in other districts. Maybe it’s out of a more self-serving desire to make it harder for opponents without access to a large number of individual donors to raise money. Either way, it’s a high-handed and arrogant conceit to believe that individuals and organizations should be forced to participate in politics in a way that mirrors just one unique district.

Ultimately, it is unclear whether Khanna’s agenda will gain any traction. Even if legislators somehow don’t see the value in PAC freedom (which is to say, freedom of association), a ban would surely face trouble in the courts, which have acknowledged campaign contributions and organizational free speech as First Amendment rights. All the same, here’s hoping that PACs continue their many decades-long trend of surviving challenges from meddling government regulations and would-be regulators.