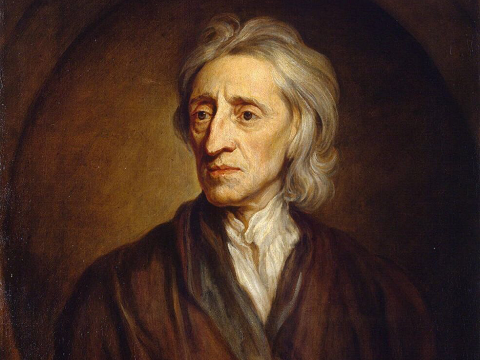

Championing the nascent liberal societies just then rising from the blood and ashes of decades of conflict over states’ asserted rights to control their subjects’ minds, souls, and bodies, John Locke’s seminal work on freedom of religion and speech taught that truth would be better served “if she were once left to [protect] her self.”[1] While a given attempt to protect the community from ideas purportedly seductive and dangerous — to control who may speak or what they may say — might be beneficent, experience and history had taught Locke that truth “is but rarely known [by], and more rarely welcome” to those wishing to stay in power, such that it is error and not truth that is generally aided “by the assistance of [government’s] forreign and borrowed Succours.”[2]

In defiance of the resulting, longstanding tradition of liberal societies and decades of First Amendment protection, a small group of Multnomah County residents convinced the county’s voters to muzzle themselves and their neighbors. Since 1976, the Supreme Court and lower federal courts have repeatedly held, across circumstances and regardless of the speaker, the government cannot limit — much less prohibit — expenditures for communications supporting or criticizing candidates, as long as those communications are made independently of a candidate. Indeed, the government cannot even limit contributions that groups receive to fund such expenditures. Nevertheless, Measure 26-184 did just that: It limited each individual and group to making no more than $5,000 and $10,000, respectively, in independent expenditures, no matter how many candidates they wish to support or oppose. It prohibited groups other than political committees from making expenditures at all. And political committees are strictly limited in the donations they may use to make expenditures.

Second, the Measure more readily delivers donors to the doxing droves, facilitating efforts to silence ideas they don’t like by threatening violence, destroying property, terminating employment, and otherwise intimidating those who dare speak unpopular ideas. By serving donors’ names on the face of the communication, the Measure not only discourages donors from giving in the first place, it alters the speaker’s message or swallows it entirely. While the Supreme Court has upheld laws requiring reporting to the government, it has held that compelled speech, like that at issue in this case, must meet the highest levels of constitutional scrutiny, and that it fails that scrutiny when alternatives are available — such as the government publishing the messages themselves, instead of forcing the content out of others’ mouths.

Third, the Measure limits contributions to candidates and to groups making independent expenditures. The Oregon Supreme Court, however, has held that the Oregon Constitution can brook no limits on contributions, and federal courts have held that the government cannot limit contributions to groups making independent expenditures — because there is little risk that contributions to those groups will result in dollars for favors between the donors and the candidates at issue. In addition, in allowing unlimited contributions by some groups but not from individuals or other groups, the Measure demonstrates that it has no interest in controlling the corruption resulting from large contributions, just in advancing the speech of preferred groups over others. This too violates foundational First Amendment principles.

On behalf of the Taxpayers Association of Oregon and the Taxpayers Association of Oregon PAC, the Institute for Free Speech filed a motion to intervene in a special proceeding to determine the Measure’s validity. While that motion was denied, the Taxpayers Association was allowed to fully brief its constitutional concerns and participate in oral argument.

[1] John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration 46 (Tully ed., Hackett 1983) (1689).

[2] Id.