On May 11, the Committee on House Administration invited Institute for Free Speech Chairman Bradley Smith to testify regarding how campaign finance laws can better respect free speech. The following letter is written testimony that Chairman Smith was invited to submit to the House Administration Committee.

At the hearing, Smith explained that the only constitutional justification for setting campaign finance contribution limits is to prevent quid pro quo corruption or the appearance of such corruption. However, many laws have drifted far from this standard. Numerous current contribution limits are so low that they burden political speech without meaningfully limiting corruption. Excessive disclosure laws are also exposing donors to harassment, which chills political speech.

Smith noted that Congress should improve current campaign finance laws by raising contribution limits and disclosure thresholds high enough to avoid burdening speech, eliminating unnecessary disclosure rules, and maintaining a bipartisan Federal Election Commission as the primary enforcer of campaign finance law.

He concluded by reminding the Committee that, “it’s important to remember that we are dealing with the essence of what it means to live in a free society—the ability to discuss candidates and ideas for how we want to be governed. When in doubt, government should always err on the side of freedom.”

Read the full letter below or in this PDF.

United States Committee on House Administration Hearing on American Confidence in Elections: Protecting Political Speech

June 7, 2023

Bradley Smith

Chairman

Institute for Free Speech

1150 Connecticut Avenue, NW Suite 801

Washington, DC 20036

Questions for the Record

Question 1:

Chairman Smith, there was testimony at the hearing that suggested voters do not vote in our elections because of the large sums of money spent in and on our elections.

a. If an eligible voter does not vote, why isn’t that a personal decision made by the voter?

b. In other words, aren’t there several reasons why a voter might not vote in an election? For example, poor candidates, lack of interest in the race, or the voter might feel uninformed about the issues and would rather stay home, etc?

c. With that in mind, can it really be said that the main reason voter turnout isn’t record-breaking in every election is because of the large sums of money in and on an election?

Answer to Question 1:

The freedom to vote necessarily carries with it the freedom not to vote. And the decision not to vote is often a personal decision on the part of an individual citizen that the government should respect.

A person may decide not to vote for many reasons. A United States Census Bureau study asked registered nonvoters in the 2016 election why they didn’t vote. The most common response was that they disliked the candidates and campaign issues. Other primary reasons were not being interested in the election, being too busy, having a scheduling conflict, and having an illness or disability.[1] The Bureau also asked eligible but unregistered voters why they had not registered. The most common reason given for not registering to vote was that the respondent was not interested in the election or political issues.[2] The amount of money in politics, and the sources of that money, did not even register as a reason for not voting. It is pure conjecture to say that money in politics is responsible for low turnout. There have been several studies over the years on the relationship between voter turnout and money in politics, and I have not found any serious evidence that higher spending or the sources of money in politics leads to lower turnout or political participation. If anything, the evidence points in the opposite direction—higher spending increases voter turnout.

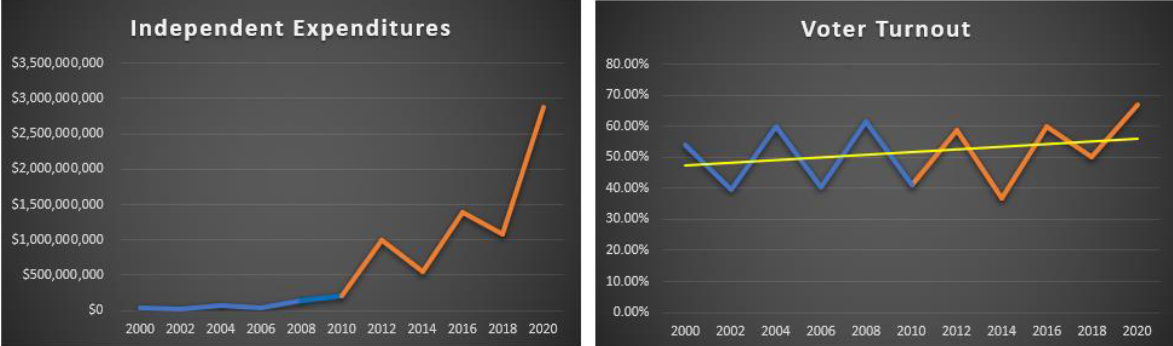

In 2021, my organization, the Institute for Free Speech, conducted a study on the relationship between voter turnout and independent spending in politics.[3] I have included two graphs from the study below. The graph on the left charts the growing amount of independent spending in elections. The graph on the right shows voter turnout over the past 20 years of elections. Turnout goes up and down based on whether it is a presidential election or not. You can clearly see from the yellow fit line that turnout has steadily increased over time. In fact, the 2020 election had the highest turnout on record and independent spending in elections was also the highest it has ever been. If money in politics was depressing turnout, then we would expect, as spending increases, turnout would decline. This has not happened. In fact, turnout has steadily increased while spending has also risen.

Many other academic studies have failed to find a relationship between higher spending in elections, or the sources of funds, and lower turnout. If anything, there is more evidence that money in politics can increase turnout and political participation by informing voters about political issues and candidate stances on issues. For example, a 2016 meta study of 185 studies on political spending and turnout found that higher campaign spending is positively linked to higher voter turnout.[4] Earlier work by political scientists John Coleman and Paul Manna found that campaign spending increases voter knowledge and helps them identify a candidate’s position on political issues.[5] The political scientists Thomas Holbrook and Aaron Weinschenk also looked at campaign spending’s effect on local elections. After investigating 340 local elections over 15 years, they found that higher campaign spending “has a statistically significant and pronounced effect on turnout levels” and that “turnout is higher in cities where candidates spend more money.”[6]

In conclusion, the evidence does not show that higher spending in political campaigns is leading to less turnout and political engagement. In fact, spending facilitates more speech and information on political issues and appears to positively impact political participation and voter turnout.

Question 2:

Out of all the money spent in our elections, roughly what percentage of that money is “dark” money?

a. Considering the percentage of “dark” money spent in our elections is a very low percentage in comparison to all other campaign spending, is there really any argument that elections are being decided solely because of “dark” money influencing the voters?

Answer to Question 2:

The term “dark money” is not a legal term and is not legally recognized in campaign finance law. Rather, it is a bit of rhetoric aimed at delegitimizing speech the speaker doesn’t like. Nevertheless, we can note that generally people argue spending is “dark” if an organization spends money to speak about political candidates, and the organization is not required to report the identities of its individual donors to the Federal Election Commission. Others, however, throw around the term more broadly. For example, if either Planned Parenthood or the National Right to Life Committee spends money from their general treasuries advocating for policies that either expand or restrict abortion access, some may label them “dark money” organizations, whether they discuss candidates and elections or not.

Because there is no clear definition of “dark money,” there is no clear answer to what percentage of total political spending so qualifies. But by any common definition, the percentage is very low. First, it is worth noting what is disclosed. All candidate campaigns, party committees, political action committees (PACs), and Super PACs disclose their donors above a de minimis amount to the Federal Election Commission. Any individual, union, or for-profit corporation that makes independent expenditures over $250 must disclose to the FEC. Any 501(c)(4) organizations (such as the Southern Poverty Law Center or the Gun Owners of America, both leading dark money spenders, according to Open Secrets) or 501(c)(6) trade associations must disclose its independent expenditures over $250, and any donors who earmarked funds for those expenditures. What is left is a small percentage of total spending. OpenSecrets estimates that $14.4 billion was spent in the 2020 election, and, apparently using a broad definition of the term, estimates that $1.05 billion, or about 7 percent, was “dark money.”[7] In 2018, the percentage, again using Open Secrets numbers, was between 2.2 and 5.2 percent, depending on how one defines “dark money.” Between 2010 and 2016, “dark money” ranged between 2.9 percent and 4.9 percent of total spending.[8] So, while it can be difficult to give a precise estimate on how much money is “dark,” we can confidently say that in every election since Citizens United was decided in 2010 spending has consistently been well under 10% of total spending, and usually under five percent, even using more expansive definitions of the term.

But even these numbers overstate the issue because many “dark money” groups and their agenda are well known to the public. For example, OpenSecrets lists the National Association of Realtors, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Black Progressive Action Coalition, The Humane Society, VoteVets, and the American Bankers Association among the top “dark money” spenders in the 2022 election cycle. Do Americans really not know what the American Bankers Association stands for or what industry it represents?

As “dark money” is a low percentage of total spending, it is incredibly unlikely that “dark money” spending is driving election results. Presumably it has some impact—that is the purpose of all political speech. But the mere fact that “dark money” spending might have some influence is not inherently a bad thing. If NARAL Pro-Choice, People for the American Way, or the NRA Institute for Legislative Action—all leading “dark money” spenders, per OpenSecrets—run a persuasive ad that convinces a previously uninformed voter to vote for or against a candidate, the organization purchasing the ad is disclosed, and the public is hardly bamboozled. Indeed, this looks exactly like democratic speech in action. It is extremely hard to believe that Americans watch an ad that says, as required by law, that it is paid for by the NRA, and feel they can’t “evaluate” the message without knowing which of their fellow Americans donates to the NRA. So, “dark money” plays a very limited role in elections and can be a plus if it informs voters about political issues they care about.

Why don’t all organizations disclose all donors? There are many reasons, but many organizations engaging in issue advocacy on sensitive or controversial issues are hesitant to disclose their donors and expose them to potential harassment, intimidation, or even violence. Organizations across the political spectrum can be “dark money” organizations if they engage in issue advocacy and don’t disclose their donors, such as the AARP, the NRA, and the Sierra Club. If the AARP spends money on an ad advocating for protecting Medicare for seniors and does not disclose who paid for the ad then this is considered “dark money spending.” The vast majority of issue-based organizations are not nefarious organizations, but are rather conduits for democratic discourse at work. The Supreme Court has long recognized the importance of privacy to political speech and action, and has accorded First Amendment protection to supporters and members of organizations that either do not engage in direct advocacy of election or defeat of candidates[9] or do so on a limited basis where it is not the organization’s primary purpose.[10]

Furthermore, excessive disclosure of donors to nonprofit organizations, in an effort to uncover the “real” donor, can produce junk disclosure, which provides misleading information to voters. For example, consider a hypothetical Republican banker who financially supports American Bankers Association and expects it to broadly represent his interest as a banker. The fact that the Bankers Association might then make independent expenditures supporting a Democrat for Congress (perhaps only in a Democratic Party primary in a safe Democratic seat) hardly means that one individual banker is the “real” source of the ad—the information is misleading rather than educational to voters. It is “junk disclosure.” When people give to organizations that does not mean they support every policy stance or candidate supported by the organization. Furthermore, when a supporter gives to an organization, it is no longer the supporter’s money. Unless the supporter has earmarked his contribution for a particular purpose, which few do (they join organizations to let the organizational management decide these things), the supporter has no legal control over the spending.

Finally, requiring reporting of the same contribution at each step in an effort to “reveal” the “true” funder actually makes it harder for voters to “follow the money.” Consider, for example, a business that contributes to its national trade association. The trade association then contributes to state affiliates that meet minimum fundraising targets of their own. The state affiliates then contribute to a statewide coalition of business associations, which then spends money on ads in a particular race for congress. Such transfers go on all the time with no nefarious purpose. Beyond the fact that it is highly dubious to call the original business the “true” funder of those ads, demanding that the funds be reported at each step will lead to multiple counting of amounts actually spent, misleading rather than informing the public, and requiring citizens to run through a complicated “backing out” of donations to get a truer estimate of spending.

Finally, many people simply don’t want to be the center of attention. In the current climate, many employees have good reason not to want their employer to know their politically related donations; many high executives don’t want their personal contributions attributed to the business for which they work, many people legitimately fear public retaliation, and so on. The First Amendment protects these people, too.

Question 3:

Can you briefly describe the Supreme Court’s holding in NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958)?

a. To be clear, that case was not a one-off, was it? Hasn’t the Court reaffirmed the freedom of association principle several times, most recently in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, 141 S.Ct. 2373 (2021)?

Answer to Question 3:

The Supreme Court decision NAACP v. Alabama is one of the most important cases upholding freedom of association. The case arose during the Civil Rights movement when the State of Alabama, as part of an investigation into whether the NAACP was complying with Alabama corporation law (it appears that it was not, though inadvertently so), attempted to force the NAACP to disclose its donors. The NAACP wanted to protect the privacy of its donors—many of whom were wealthy whites from the northeast—because they were reasonably worried that exposing their donors would lead to discrimination, harassment, and potentially violence against its members. In 1958, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of the NAACP and explained that “Inviolability of privacy in group association may in many circumstances be indispensable to preservation of freedom of association, particularly where a group espouses dissident beliefs.”[11]

NAACP v. Alabama was not an unusual case defending associational rights, and it was followed by many cases that affirmed the right of privacy and association under the First Amendment. For example, in 1960 the Supreme Court case Shelton v. Tucker struck down an Arkansas law that required teachers to list all their associations over five years.[12] In Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Commission, the Court prevented Florida from compelling the release of membership lists of groups the government was investigating as “subversive organizations.”[13] In the famous campaign finance case Buckley v. Valeo, the Court stated that “compelled disclosure, in itself, can seriously infringe on privacy of association and belief guaranteed by the First Amendment… significant encroachments on First Amendment rights of the sort that compelled disclosure imposes cannot be justified by a mere showing of some legitimate government interest.”[14] In the 1986 case Massachusetts Citizens for Life, the Supreme Court raised concerns with the burdens that compelled disclosure laws placed on organizations that required tracking and updating information.[15] Justice O’Connor also wrote an opinion raising concerns about poorly constructed disclosure requirements imposing “organizational restraints,” and harming the functioning of nonprofit organizations.[16]

In 2021, the Supreme Court added to this long line of precedent defending free association in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, when it struck down a California law that collected sensitive information about nonprofit organization donors for “mere administrative convenience.” The Court invalidated the California dragnet scheme that collected large amounts of private information because the government did not narrowly tailor its disclosure requirements to an important government interest.[17]

As you can see, NAACP v. Alabama and AFPF v. Bonta are not one-off cases. Instead, they are bookends on a robust line of Supreme Court precedents that defend the freedom to associate without being subjected to unreasonable government efforts that chill free association.

Question 4:

We heard some testimony at the hearing that the disclosure holding in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) was broad, open-ended, and might allow Congress and the States to ask groups to disclose on any number of issues.

a. Please briefly describe the disclosure holding in Citizens United.

b. In your opinion, was the disclosure holding broad and open-ended that allows Congress and the States to ask for any type of disclosure? Or was Citizens United about something entirely different and narrower than cases like NAACP and Bonta?

c. If Citizens United’s disclosure holding was so broad and open-ended as was suggested at the hearing, did the Court reach the wrong decision in Bonta?

Answer to Question 4:

The Citizens United v. FEC ruling stated that it was unconstitutional to limit independent spending by corporations and unions on political issues. The decision’s main holding was not related to disclosure and the Supreme Court in this case did not make any major changes to its compulsory disclosure jurisprudence. The Supreme Court noted in Citizens United that “The Government may regulate corporate political speech through disclaimer and disclosure requirements, but it may not suppress that speech altogether.”[18] In recognizing that not all disclosure laws are unconstitutional, the Court simply reaffirmed the disclosure standards from the campaign finance case Buckley v. Valeo. In Buckley, the court recognized that disclosure rules can indirectly burden speech, and so should be subjected to “exacting scrutiny.”[19] This standard requires that a disclosure rule must meet a sufficiently important government interest and be narrowly tailored to meet this interest. Disclosure laws that meet these requirements can be constitutional. But Buckley severely limited what had been sweeping disclosure provisions in the Federal Election Campaign Act amendments of 1974. Whereas the amendments required disclosure of expenditures “relative to” a candidate in excess of $1000, the Court limited that disclosure to organizations with a primary purpose of influencing an election, such as candidate and party committees, and to other organizations only if they expressly advocated the election or defeat of a candidate. Further, organizations in that last category were not required to disclose their donors unless those donors earmarked contributions for political advocacy.

In Citizens United, the Court determined that the communications in question were express advocacy, and hence subject to existing disclosure laws. It neither broadened nor narrowed Buckley’s restrictions on disclosure.

More recently, in AFPF v. Bonta, the Court struck down a California disclosure requirement on nonprofits that failed to meet the “exacting scrutiny” test established in Buckley and reaffirmed in Citizens United.[20] These three decisions—Buckley, Citizens United, and Bonta—are not in tension with one another. Rather, all three constrain the government from imposing disclosure regulations that violate basic political speech rights protected under the First Amendment.

Question 5:

In Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976), the Supreme Court’s per curiam opinion was clear that there is only one constitutional reason for the government to restrict spending in our elections—actual quid pro quo corruption, or its appearance.

a. Didn’t the Court reject the idea that money could be restricted to equalize the playing field for all voters or to reduce the amount of money spent on campaigns?

b. Why do you think those reasons for restricting money were rejected?

Answer to Question 5:

The landmark campaign finance case Buckley v. Valeo explicitly ruled that regulations on campaign finance spending to level the playing field or equalize the amount of influence in our political system are invalid. The Court, in a 7-1 decision, explained that “the concept that government may restrict the speech of some elements of our society in order to enhance the relative voice of others is wholly foreign to the First Amendment.”[21] The Court said that the only legitimate reasons for regulating campaign finance spending is to prevent quid pro quo corruption or the appearance of quid pro quo corruption. This means that using spending limits to try to equalize the amount of money that can be spent by different groups is unconstitutional and not a legitimate government interest.

The Buckley Court noted that a core aim of the First Amendment is to promote “the widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources” and “to assure unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people.”[22] Spending limits for campaigns fundamentally compromise the ability to fully disseminate political speech and are directly at odds with basic First Amendment protections. The First Amendment defends free expression for all speakers and protects everyone from the government being able to select its favorite speakers or attempt to suppress the ideas or viewpoints it disagrees with. Allowing the government to determine what the “right amount” of spending is in elections effectively grants them the right to determine the “right amount” of speech in our political system. The First Amendment correctly restricts the government from making these kinds of judgements and leaves it up to the citizens to consider arguments and make up their own minds.

Long before Buckley, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes famously defended free expression in a “marketplace of ideas” by saying that “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.”[23] Marketplaces are going to naturally generate some inequalities because certain speakers and products will be more successful than others and drive out inferior products and ideas. For instance, the New York Times and Wall Street Journal Editorial Boards command much more influence in our society and their speech carries more weight than a random internet blogger. Yes, there is inequality in influence between major newspapers and unknown bloggers, but this is not a bad thing. These newspapers have been able to get their ideas accepted in our marketplace of ideas and trying to equalize their influence with other speakers can undermine the democratic process and our search for truth.

The justices in Buckley’s 7-1 majority understood that accepting these equality arguments would undermine all First Amendment protections. Any restriction could be justified on some vague claim that one person was speaking too much, another too little. This is why quid pro corruption and the appearance of quid pro quo corruption are the only recognized legitimate reasons for the government to restrict money in politics.

Question 6:

At the hearing, we heard some testimony about a scandal involving the conviction of the Speaker of the Ohio House and the former Chair of the Ohio Republican Party in a federal racketeering trial.

a. Is there anything you would like to add to what was said at the hearing on this topic?

Answer to Question 6:

Unlike those who commented at length at the hearing on the racketeering trial of former Representative Larry Householder and his aide Matt Borges, I am from Ohio. The evidence shows that these individuals abused their power and abused the trust of the people of Ohio. They were removed from office and were investigated, tried, and convicted. Usually, when a person is convicted of a crime, we do not think of that conviction as a justification for burdening the rights of the vast majority of citizens with new laws and regulations. The First Amendment does not shield Householder and Borges from accountability, and they were rightly punished for their crimes.

Because Householder and Borges illegally used 501(c)4 groups in their scheme, some have argued that this justifies more donor disclosure from 501(c)(4) organizations generally, which is sort of like saying that because Householder was Ohio’s Speaker of the House, we should abolish the position of speaker. It was quite clear to anyone paying attention in Ohio that the ballot initiative at the heart of the scandal was intended to benefit energy companies operating in Ohio, and that the campaign for the initiatives was largely funded by energy companies. The initiative was aggressively criticized and members of the public and legislators had the ability to hear these positions and weigh in on the issues. (I note here that I also serve as Chairman of the Board of the Buckeye Institute, an Ohio think-tank that vigorously criticized the ballot initiative.) The use of 501(c)4 groups to spread a message was not the problem—it was the underlying bribes, racketeering, and abuse of power which was the problem.

Adding disclosure burdens on all 501(c)4 groups would not have stopped the scandal—it would simply have forced Householder to use a different vehicle. And if Householder was not above accepting bribes, it is strange to think that he would have refused to violate relatively obscure campaign finance disclosure rules.

As noted above, typically, when a thief is convicted of a crime, we don’t consider that conviction as evidence of the need to violate other citizens’ 4th, 5th, or 6th Amendment rights. We shouldn’t take that approach here either.

I hope that this answers all of the committee’s questions. Please feel free to reach out if I can be of any further assistance to the committee.

Sincerely,

Bradley Smith

[1] Thomas File, “Characteristics of Voters in the Presidential Election of 2016,” United States Census Bureau, 2018, 14, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p20-582.html.

[2] Ibid, 16.

[3] Alec Greven, “Issue Analysis No. 12: Did Citizens United Harm Political Participation? A Comparison of Independent Expenditures and Voter Turnout,” Institute For Free Speech, 2021, https://www.ifs.org/research/issue-analysis-12-citizens-united-political-participation/.

[4] João Cancela and Benny Geys, “Explaining voter turnout: A meta-analysis of national and subnational elections,” Electoral Studies. Vol. 42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005 (June 2016) at 264-275.

[5] John J. Coleman and Paul F. Manna, “Congressional Campaign Spending and the Quality of Democracy,” The Journal of Politics. Vol. 62:3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00032 (Aug. 2000) at 757-89.

[6] Thomas M. Holbrook and Aaron C. Weinschenk, “Campaigns, Mobilization, and Turnout in Mayoral Elections, Political Research Quarterly. Vol. 67:1. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23612034 (March 2014) at 48.

[7] Karl Evers-Hillstrom, “Most Expensive Ever: 2020 Election Cost $14.4 Billion,” Open Secrets, February 11, 2021, https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2021/02/2020-cycle-cost-14p4-billion-doubling-16/.

[8] Luke Wachob, Putting “Dark Money” In Context: Total Campaign Spending by Political Committees and Nonprofits per Election Cycle, Institute for Free Speech, May 16, 2017, at https://www.ifs.org/blog/putting-dark-money-in-context-total-campaign-spending-by-political-committees-and-nonprofits-per-election-cycle/.

[9] NAACP v. Alabama 357 U.S. 449 (1958).

[10] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976).

[11] NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449, 462-463 (1958).

[12] Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960).

[13] Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Comm., 372 U.S. 539 (1963).

[14] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 424 (1976).

[15] FEC v. Massachusetts Citizens for Life, 479 U.S. 253 (1986).

[16] Ibid, 479.

[17] Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, 594 U.S. _ (2021).

[18] Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010).

[19] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 424 (1976).

[20] Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, 594 U.S. _ (2021).

[21] Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 48-49 (1976).

[22] Ibid, 49. These quotes are also drawn from prior Supreme Court precedents.

[23] Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 630 (1919). (Justice Holmes dissenting).