The Institute for Free Speech is pleased to present the Free Speech Index: Grading the 50 States on the Freedom To Speak About Government. It is a first-of-its-kind analysis of laws restricting speech about government in all 50 states. This Index is the most comprehensive examination of state laws governing and regulating political engagement ever published.

The Free Speech Index rates each state on how well it supports the free speech and association rights of individuals and groups interested in speaking about candidates, issues of public policy, and their government.

To assess each state’s performance, we ranked the states in ten categories, each of which examine a different area of state law burdening speakers and groups.

To find out how your state performs, see the map below.

Table of Contents

A Note About Contribution Limits and the 2018 Free Speech Index

Foreword by Institute for Free Speech Chairman and Founder, Bradley A. Smith

On behalf of the Institute for Free Speech, I am pleased to present the Free Speech Index: A first-of-its-kind analysis of laws restricting speech about government in all 50 states. This Index is the most comprehensive examination of state laws governing and regulating political engagement ever published.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution states that “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” Unfortunately, Congress and the states have passed too many laws limiting these rights. Federal campaign finance laws and regulations contain over 376,000 words, but as this Index shows, this statistic only scratches the surface. Each of the 50 states has its own collection of campaign finance laws and regulations limiting the freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and petition. Many of these state laws are poorly written, complex, or both.

Despite advances in constitutional protections for speech in the courts over the last decade, our politics – and campaign finance law in particular – remains more highly regulated than at any time prior to the 1970s. In some important ways, our speech has never been more highly regulated. Though campaign speech is often portrayed as a “wild west” with no rules, in fact, arcane campaign finance regulations govern the minutiae not only of almost every campaign, but of what ordinary citizens and the groups they belong to can say and how and when they can say it.

This is the second Index published by the Institute. The first edition of the Free Speech Index, published in 2018, was a groundbreaking survey of state laws that determined whose laws on political giving were most protective of free speech. For the first time, legislators, reporters, and most importantly, citizens, had a tool to evaluate their state’s performance on the core measure of voters’ ability to support the political candidates of their choice, free from state interference.

But that Index evaluates only one part of the equation: contributing to candidates, parties, and political causes. This second installment evaluates how well states protect freedom of speech and association for individuals and groups when they engage in the political process. The Index examines state laws on ten important measures of political freedom and participation, including the right to engage in grassroots advocacy campaigns, to join with fellow citizens to form “political committees,” to control the content of their own political messages free from government interference, to advocate for the election or defeat of candidates as they see fit, and to support unpopular or disfavored causes without fear of government retribution.

Laws regulating political engagement and the accompanying harms they cause to free speech and association are often presented as necessary to “good government.” But good government does not go hand-in-hand with regulation of citizen political activity. The complex maze of laws that result make it extremely difficult for citizens to even evaluate the overall climate for free speech about public affairs in their states; this, in turn, allows government officials to avoid the accountability that comes from citizen activism. The Index is a crucial tool for citizens seeking to evaluate their state laws – and hold officials more accountable. Based on the 10 criteria we examined, for example, New York and Connecticut place more restrictions on citizen political engagement than any other states. Voters and activists in those states can ask themselves if they feel that these restrictions have led to “good government.” At the Institute for Free Speech, we believe that good government is most likely when individual liberties are protected. First Amendment speech freedoms should not be an afterthought when lawmakers pass campaign finance, lobbying, or other laws regulating public participation in support of issues or candidates. The ability to measure a state’s regulation of free speech allows us – and you – to put this belief to the test.

In addition to its worth as a tool for evaluating the efficacy of political speech regulation, the Index is a tremendous resource simply for gathering in one place, for the first time, the vast array of state laws regulating Americans’ ability to participate and engage in public life.

We trust that the Index will be both a useful guide to the broad array of laws governing political participation in America and a valuable tool for citizens and policymakers seeking to measure the performance of their own representatives and determine the value of regulating political speech.

Executive Summary

This installment of the Free Speech Index rates each state on how well it supports the free speech and association rights of individuals and groups interested in speaking about candidates, issues of public policy, and their government.

To assess each state’s performance, we ranked the states in ten categories, each of which examine a different area of state law burdening speakers and groups:

• Laws on Political Committees

• Grassroots Advocacy and Lobbying

• Definition of Campaign “Expenditure”

• Regulation of Issue Speech Near an Election (“Electioneering Communications”)

• Regulation of Independent Expenditures by Non-Political Committees

• Coordination Regulations

• Disclaimers

• Super PAC Recognition

• False Statement Laws

• Private Enforcement of Campaign Laws

In each category, states earn the greatest number of points if their laws either do not burden or impose relatively small burdens on citizens’ First Amendment rights. Such states make it easier for citizens to speak about issues and the government. States receive no points if their laws fail these tests, heavily burdening the right of its citizens to speak about their government. Because of the exceedingly complicated nature of state laws in these ten categories, the task of determining the relative burdens of each statute on First Amendment rights is difficult. To overcome this complexity, the Index breaks down each category into subcategories that examine highly specific areas of the law. The subcategories and categories are then weighted based on how much of an impact they have on free speech.

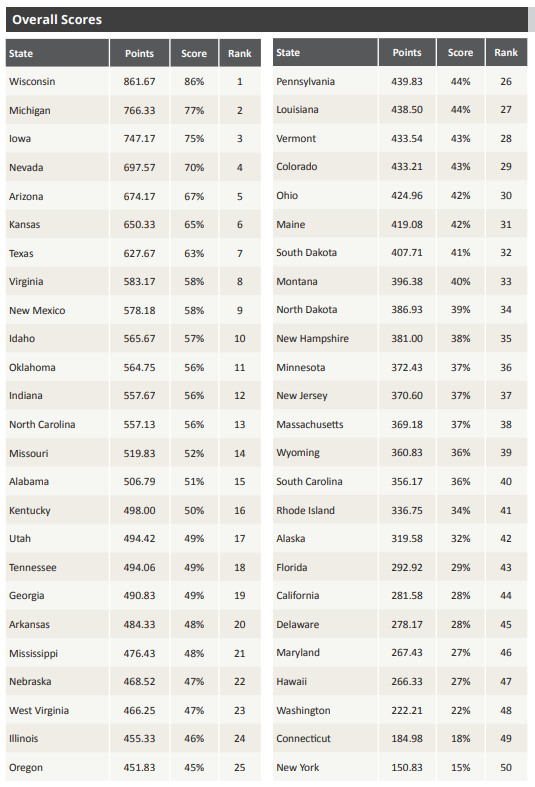

A state could earn a maximum of 1000 points in the Index if its laws impose minimal burdens on free political speech.

Unfortunately, few states come close to this mark. Only three (3) states (Wisconsin, Michigan, and Iowa) achieve a score above 700 points. And only one (Wisconsin) manages to top 800 points.

Thirty-five states earn a score below 500 points, and eight (8) states (Florida, California, Delaware, Maryland, Hawaii, Washington, Connecticut, and New York) earn a score below 300 points. New York comes in last place with an abysmal 151 points.

This result reflects the sad reality that speech about government is stringently restricted across the country. The failures are seen in traditionally “red” states like Alaska (rank #42) and Florida (#43) and “blue” states like Connecticut (#49) and Hawaii (#47), in big states like California (#44) and small states like Delaware (#45), and in states east (New York, #50), west (Washington, #48), north (Minnesota, #36), and south (South Carolina, #40).

In what areas of the law are most states failing? Looking deeper into the ten categories, we begin to see some consistent trends.

• Only eight (8) states (Louisiana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Arizona, Virginia, Wisconsin, Texas, and Utah) earn more than a 50% score based on their laws on political committees.

• Only ten (10) states (Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Nevada, Rhode Island, Texas, and West Virginia) earn more than a 50% score based on their definition of campaign “expenditure.”

• Only thirteen (13) states (Alabama, Indiana, New Mexico, Wisconsin, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Tennessee, Illinois, Montana, Nevada, and Texas) earn more than a 50% score based on their coordination regulations.

These three areas represent a nationwide failure from a First Amendment perspective. Across the country, states are regulating too much speech by broadly defining what kind of groups are regulated and how much of and what types of activity must be regulated. Most states are simply not considering the First Amendment impacts in these areas.

Other important categories see divergent approaches, with some states imposing no or minimal burdens on free speech, while others impose excessive ones. The worst states in the Index typically go above and beyond in an effort to regulate and control as much speech as possible, even beyond what is constitutionally permissible.

• Twenty-four (24) states have no regulation of issue speech near an election (“electioneering communications”) and receive full points in that category. But eleven (11) states (Rhode Island, Maryland, Connecticut, Illinois, West Virginia, Florida, Delaware, Idaho, New York, Montana, and Alabama) regulate speech in this category so severely that they receive scores at or below 25%.

• Thirty-five (35) states have no regulation (or limited regulation) of grassroots advocacy. But six (6) states (Washington, Wyoming, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, New York, and New Jersey) regulate grassroots advocacy so harshly that they receive scores at or below 25%.

• Twenty-six (26) states have speech-friendly laws regulating independent expenditures by non-political committees (scoring 70% or greater), but twenty-two (22) states have highly restrictive laws in this area (scoring 25% or lower).

• Ten (10) states (Alaska, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, and Washington) have such burdensome disclaimers that the states receive 0% in that category.

• Eight (8) states (Alaska, California, Delaware, Idaho, Massachusetts, South Carolina, Texas, and Washington) allow private enforcement of campaign laws – enforcement of the law directly by one’s political opponents.

Finally, some states deserve opprobrium for particularly blatant First Amendment violations.

• Nineteen (19) states still have unconstitutional false statement laws enshrined in statute.

• Twenty-two (22) states still have unconstitutional laws that fail to recognize super PACs.

• In both instances, such laws were declared unconstitutional beginning over a decade ago. Yet, six (6) states (Alaska, Indiana, Louisiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Ohio) still have both deficiencies in their laws.

These observations are just the tip of the iceberg. This Index is intended to aid the public, scholars, journalists, and policymakers in examining why these states fail at protecting speech about government and what effect that has on how well states function and their elected officials govern.

How States Can Improve

This section contains general recommendations for those interested in improving their state’s score in future editions of this version of the Free Speech Index. To see where your state lost points, see the State Report Cards beginning on page 71. Specific recommendations on model policies appear on the second page of each State Report Card. Following those model policies will lead to substantial improvements in each state’s law to better conform with Supreme Court precedents and better fulfill the spirit of the First Amendment.

A complete listing of all the variables graded and the points assigned to each is available in the Methodology beginning on page 175.

I. Follow the Constitution

The easiest way for states to embrace a First Amendment-friendly approach is to simply repeal or amend statutes that are clearly unconstitutional. Forty-five states have statutes that are of questionable constitutionality and would likely not survive, if challenged in court. Many of these statutes have already been ruled unconstitutional, yet they remain on the books, chilling potential speech and activity. Eliminating these provisions will improve the ability of groups and citizens to make their views known. Further, repealing unconstitutional provisions will save a state time and money when offending provisions are challenged and the state loses in court. The Institute for Free Speech recommends several First Amendment-friendly changes to remove unconstitutional provisions seen in many states.

Raise severely low monetary thresholds for political committee registration and reporting. Thresholds under $1,000 have repeatedly been struck down by courts. As one court put it, “the informational interest” of reports from such small groups “is outweighed by the substantial and serious burdens” that such reports entail. Yet 34 states have thresholds for political committee registration below this level. These limits should be raised dramatically.

Follow Supreme Court guidance for defining the term “expenditure.” In Buckley v. Valeo, the Supreme Court allowed for the limited regulation of spending on campaign speech that specifically and overtly “advocate[s] the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate.” For 45 years, states have pushed the envelope – attempting to regulate more and more speech by expanding what speech qualifies as an expenditure. State regimes with broad definitions of “expenditure” have regularly been found by courts to unconstitutionally restrict too much speech. States should heed this case law and hew their laws to only the narrow, Supreme Court-sanctioned definition.

Legalize super PACs. For over a decade it has been clear that it is unconstitutional to limit contributions to independent expenditure-only political committees, more commonly known as “super PACs.” In 2010, the en banc United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit struck down analogous federal limits in SpeechNow.org v FEC. Since that ruling, at least five more federal courts of appeals have considered this issue, and in each case the ruling was the same – such restrictions are unconstitutional. Yet 22 states still have laws restricting these contributions. These unconstitutional statutes should be repealed, and formal recognition of super PACs should be enacted.

Repeal false statement laws. The Supreme Court has long affirmed that the government cannot decide what is true or false. Specifically, in the political context, such laws were unequivocally found to be unconstitutional in 2014. Yet 19 states still have laws prohibiting false political speech, as determined by politicians and regulators. These statutes should be repealed.

Exempt public information from coordination rules. Publishing information, whether in pamphlets or on websites, is protected by the Constitution. But because of the incredible complexity and invasiveness of some laws regulating campaign speech, that right has been violated by states’ bans on coordination between independent groups and campaigns. States should fix these statutes and make clear that using publicly available information in communications is not evidence of illegal coordination. Only ten states currently have statutes protecting against this constitutional violation.

II. Protect Citizen Privacy

To best protect free speech, states must understand the essential link between citizens’ right to privacy and citizens’ speech. If an individual’s personal information is reported to the government and then published on the internet for all to see forever, they are less likely to contribute to groups or causes. This is especially true when the speech they are supporting is unpopular, controversial, or disfavored by those in power. Strict disclosure rules lead to a climate with less free and open speech. In the 1950s, the Supreme Court ruled that Alabama’s disclosure demands aimed at exposing the NAACP’s membership were a violation of the First Amendment. Unfortunately, privacy from government disclosure laws for those engaged in issue speech is increasingly under attack in many states. The Institute for Free Speech suggests several First Amendment-friendly changes to better protect citizens’ privacy.

Eliminate donor reporting for groups whose main purpose is not campaign speech. Maximizing speech means making it easy for groups to exist and speak out in the manner of their choosing. For some groups, that means engaging in issue speech most of the time, but occasionally speaking to urge the election or defeat of certain candidates. By demanding donor reporting for such groups, states limit their ability to speak and wrongly risk the harassment of their supporters. Twenty-seven states make some effort to protect the privacy of these donors and the speech rights of these groups. But all states should recognize the value of this speech.

Reject grassroots advocacy regulation. Citizens have a right to talk about policy issues and legislation without fear of reprisal or harassment for their views. Such protections for advocacy, particular for advocacy of unpopular or dissenting opinions, should be celebrated by legislators as a cornerstone of democracy. Nineteen states allow full freedom for groups to push for social change. Unfortunately, 31 states regulate this speech, forcing speakers to register with the government before engaging in issue speech. Worse, 12 states go one step further, forcing supporters of these speakers to also be reported to the government. Such laws should be repealed to protect citizens’ privacy and create a speech-friendly environment where civic debate can thrive.

Raise thresholds for all donor reporting. Public reporting of donors has been allowed by the Supreme Court to protect against corruption and its appearance. States that require any donor reporting should make this justification the sole focus of their statute. To that end, does a $50 contribution corrupt? Or $25 to a political committee? What about a single dollar given by a citizen to a candidate, which is the threshold in some states? Subjecting donors of such small amounts to the risks of public disclosure must be weighed against the benefit of reducing corruption. Incredibly, 44 states have at least one donor reporting threshold below $200.

Limit reported contributions to those specified for the speech. Inevitably, some state lawmakers will remain convinced that the informational interest of disclosure outweighs the privacy concerns with donor reporting. Even pro-disclosure policymakers can, however, make some strides to protect both interests. By limiting reporting of contributions solely to donations earmarked for speech – that is, specifically donated for a particular purpose – lawmakers can protect the privacy of donors that give generally. This has the additional benefit of avoiding junk disclosure that misattributes contributions to speech that a donor did not fund. Eighteen states already limit some reporting rules to only earmarked contributions.

Eliminate employer disclosure. Some lawmakers continue to push for public disclosure of a contributor’s employer, arguing that these laws inform the public. Many of these laws, however, have the opposite effect, creating misinformation and misleading the public about the source of a candidate or group’s support. These reports allow media outlets, either through ignorance or to further a desired narrative, to misattribute a contribution from an individual to their employer. This disclosure incentivizes the creation of stories like “Candidate Jones receives the most money from Big Tech” when it was, in fact, illegal for the candidate to take any money from those corporations, and the campaign instead received individual donations from employees of a company. Over 30 states require some form of employer disclosure, but even legislators who otherwise believe in the informational value of reporting should look to eliminate these provisions to prevent misinformation.

Eliminate donor disclosure on disclaimers. The harms of donor reporting are well-established: by making Americans’ personal information public, these laws make speakers vulnerable to harassment and retribution. But ten states go even further, compelling groups to list certain donors on ads that they run. Such measures significantly amplify the risks associated with public disclosure and are obviously meant to dissuade contributors to disfavored causes. These rules also force a speaker to pay to broadcast this mandatory invitation for harassment of their supporters. Some laws are so severe that up to half a 30-second ad can be taken up by disclaimers with donor disclosure. These laws should be repealed.

III. Think Speech First

The most fundamental change all policymakers need to make in this area is to think first and foremost about the impacts on speech. When lawmakers write an “expenditure” definition, they should understand they are defining what spending on speech will be regulated. When policymakers seek to regulate the activity of committees, they are regulating the speech of the citizens who make up that committee. When lawmakers advocate for new campaign finance laws for the internet, new laws close to an election, or more disclosure rules for certain types of groups, they are regulating groups and individuals based on their speech. This realization is crucial to understanding the impact these laws have and should encourage lawmakers to legislate with a light hand. The Institute for Free Speech advocates for several policy changes that prioritize speech.

Narrow overly broad expenditure and coordination definitions. The majority of expenditures by political and issue groups, from bumper stickers to campaign events to television ads, go toward speech. When a state has a broad expenditure definition, it necessarily captures more speech. Expansive definitions often force groups to hire expensive attorneys to provide guidance on when and how to follow the law, and if the law applies at all. The end result is more groups, farther afield from the law’s intended targets, are regulated and burdened. The same is true when defining what spending counts as “coordination.” Only six states think about the speech consequences first and have an expenditure definition narrow enough to not unnecessarily burden more speech than needed.

Ensure laws regulating when a group becomes a political committee capture only those groups engaged in campaign speech. In a flourishing democracy, anyone should be able to speak in whatever form they think is most effective. That means some groups will want to talk about candidates exclusively, some will want to focus on issues, and some will do a mix of both. But legislators often ignore the speech implications of defining which group is or is not “political.” The result is definitions that are confusing, vague, and contradictory. If groups don’t know where the lines are drawn, it is more difficult to speak about the causes they seek to promote. Lawmakers should simplify these rules, making sure that regulation affects only the intended speakers and no one else.

Eliminate so-called “electioneering communications” laws, or at least limit their reach to specific times and circumstances. Speech about public policy is among the most valuable speech that exists in a democracy. Such speech, however, will inevitably entail mentioning the names of current officeholders, whether their action is needed to turn an idea into law, they are famous for their opposition to an issue, or they’ve simply attached their name to a piece of legislation. And discussing policy when the public is most focused on political debate – near elections – is also the most effective advocacy. Despite this, 26 states impose burdens on this type of speech. Some lawmakers view such regulations as an extension of campaign rules but are woefully ignorant of the harms to issue speech. In some states, policymakers have extended these regulations to encompass nearly the entire year of an election and any mention of any candidate. This is a serious mistake. Legislators should consider the speech implications of these statutes and limit or repeal them.

Make disclaimers simple. Disclaimers on ads are the government’s words that citizens have to pay for. This should be the framework that lawmakers use when thinking about disclaimers – they are compelled speech. Given this reality, lawmakers should strive to minimize their impact on speakers. Disclaimers should be short, unbiased, and flexible to allow for different types of speech and yet unseen methods of technological innovation. Successful implementation will inform voters about the source of a message while keeping compliance burdens manageable for speakers. By not thinking about the nature of compelling others to carry the government’s message, nearly all states’ disclaimer rules are too proscriptive and burdensome.

Adjust all monetary thresholds for inflation. A dollar today is worth less than a dollar in the past. Nevertheless, many states set monetary thresholds in legislation nearly fifty years ago and have not updated their laws since. These thresholds run the gamut, from how much spending triggers registration and reporting requirements for different types of committees to how large a contribution must be to require reporting of a contributor’s personal information. As a result of this system, regulations unnecessarily capture ever smaller groups, more private information, and more speech over time. Adjusting these thresholds for inflation is a simple and uncontroversial way for states to acknowledge that small speakers and contributors do not need to be regulated by the government.

A Note About Contribution Limits and the 2018 Free Speech Index

Educated observers will notice that, while this Index surveys in great detail the ability of individuals and groups to speak and publish information about government, it overlooks another restriction: the freedom of individuals to contribute to those groups that speak about candidates and causes.

In 2018, the Institute for Free Speech released the inaugural Free Speech Index – Grading the 50 States on Political Giving Freedom. That publication covers restrictions on exactly that freedom: whether and how states restrict Americans’ ability to contribute to candidates, political parties, and political groups. That 2018 Index, consequently, measures the First Amendment right of Americans to contribute, while this Index assesses the First Amendment right of Americans to organize and spend money on political advocacy or issue speech.

Contributing to campaigns, parties, and political groups is among the most simple and effective avenue through which citizens can participate in the democratic process and make their voices heard. Unfortunately, as readers of the first Index know, Americans across the country face severe restrictions on this fundamental freedom. But there was good news in our findings. Citizens in most states are free to donate without restriction in at least one of the categories we studied in that Index.

The 2018 Index found that 28 states allowed unlimited donations from individuals to political parties. Twenty-two permitted parties to provide unlimited support to their candidates. Eleven states had no limits on the ability of individuals, parties, or PACs to support candidates. Additionally, 32 states allowed unions, corporations, or both to give directly to candidate campaigns.

The first installment of the Free Speech Index ranked and graded each state based on nineteen variables grouped into five categories. Eleven states received an A+ or A grade. The top eleven rated states overall were: Alabama, Nebraska, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia (each tied for #1), Mississippi (#6), Iowa (#7), Indiana (#8), and North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and Texas (each tied for #9). All eleven states allow individuals, parties, and PACs to contribute to candidates without limit. Notably, these states are diverse in size, population, geography, and politics. They include large states (Texas), less populated states (North Dakota), eastern states (Pennsylvania), western states (Utah), blue states (Oregon), and red states (Alabama).

The five states tied for #1, which received an A+ grade, had no limits in any of the categories we studied. They permit individuals, political parties, and PACs to support the candidates, parties, and causes of their choice. These states also allow unlimited donations from unions and businesses to candidate campaigns.

Just one state – Iowa – performs very well in both Indices. It appears to offer the greatest amount of freedom of any state for citizens who wish to advocate for better government.

Sadly, eleven states received a failing grade in the 2018 Index due to their restrictions on political giving freedom. The five lowest scores went to Kentucky, West Virginia, Alaska, Colorado, and Maryland. Since publication, some states, like West Virginia, have raised their limits in recognition of the importance of robustly supporting their residents’ right to express support for their favored candidates.

Sadly, four states – notably Alaska, Connecticut, Maryland, and Rhode Island – ranked in the bottom ten in both Indices. These are, unquestionably, some of the most regulated and hostile states in the country for those who want to advocate for better government.

The full list of scores and grades from The Free Speech Index – Grading the 50 States on Political Giving Freedom is available here. While this Index and the 2018 installment measure different freedoms, taken together, they provide an insightful review of a state’s respect for citizens’ ability to advocate for better government as guaranteed by the First Amendment.

Why We Published This Index

In 2008, Coloradan Diana Brickell (then Hsieh) published a 34-page, heavily footnoted paper explaining and criticizing the Personhood Movement. In the final sentence, Diana wrote “if you believe that ‘human life has value,’ the only moral choice is to vote against Amendment 62,” a pro-life Colorado ballot measure supported by the Personhood Movement. Diana, and her co-author Ari Armstrong, published the paper on the website of their nonprofit, Coalition for Secular Government, which they founded to promote a secular understanding of individual rights, including freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state. Her paper, and efforts by CSG to promote her work, eventually caused Colorado to regulate CSG and Diana in much the same manner as if she were running for governor.

Diana was shocked. She had no idea her modest efforts to distribute her philosophical treatise to the public would be treated like a campaign ad by state regulators. Suddenly, she found herself forced to catalog practically every dollar the duo spent or received to support their work. Every office supply purchase had to be recorded. Even small donors had to be exposed to state officials. Once, Diana was one day late filing her report because her house had flooded. The state tried to fine her for the delay.

With help from Institute for Free Speech attorneys, Diana finally vindicated her rights over four years later after a long and winding court battle. But the fight had taken its toll. As Diana lamented, “Our experiences with Colorado’s system have been confusing and dispiriting. We’ve not abandoned our efforts, as most people would have done, but we’ve definitely scaled back our efforts. We shouldn’t have to register and file these meaningless reports with the State to speak on moral and political topics of public concern.” Sadly, what Diana experienced is increasingly common. Americans who exercise their First Amendment right to speak about government are routinely overwhelmed by state laws and regulations.

In 2013, Nicole Theis, the President of the nonprofit Delaware Strong Families, planned to produce a Values Voter Guide that outlined where local candidates stood on issues important to her organization’s members. The group had published similar voter guides in previous elections. They asked candidates questions about many different issues, including controversial topics like human cloning and late-term abortion, and then published their answers so voters could educate themselves on the candidates’ positions. The voter guides never endorsed or excluded any candidates, and they encouraged voters to do their own research to learn more. The guides were scrupulously nonpartisan, meeting all IRS rules for a nonprofit, which prohibit any electioneering.

That year, however, Delaware passed a new “electioneering communication” law that regulated this publication like a campaign ad. For Theis, the cost of educating her community about issues she and her members cared about now carried significant burdens. Most concerning, she would have to publicly expose the personal information of all supporters of the group who contributed as little as $9 a month. Not wanting to betray the privacy of her members, Nicole turned to the Institute for Free Speech for help. We fought for her right to publish her group’s Voter Guide free from these burdens. A federal district court agreed the law was unconstitutional, but the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed that decision and upheld the law. Nicole was forced to choose between her right to speak and her members’ privacy. The Voter Guide ceased publication, and voters no longer had access to the information.

Citizens who speak directly to legislators, instead of the public, can end up in a similar bind. Just ask Missouri rancher and citizen-activist Ron Calzone. Ron frequently travels to the State Capitol in Jefferson City to speak to lawmakers and testify about bills before the legislature, advocating for individual liberty and limited government. His penchant for getting in powerful politicians’ way did not go unnoticed. In 2014, Ron was reported to the Missouri Ethics Commission for allegedly failing to register as a lobbyist, despite never being paid for his efforts and never giving any gifts to legislators. Nevertheless, he was fined $1,000. If he continued to speak his mind, he was threatened with more fines and possible jail time. In court, Ron later discovered that the complaint against him was an act of retaliation, filed by the Missouri lobbyist guild on behalf of state legislators who didn’t like what Ron had to say about their bills.

The Institute for Free Speech took the case and, after more than five years, Ron prevailed. A federal court eventually reached the clear conclusion: A citizen speaking to lawmakers and testifying about bills, while exchanging no money whatsoever in the process, is not a lobbyist. He is an American exercising his First Amendment rights to speak and petition the government for a redress of grievances. Yet this happy ending was tempered by the difficult and prolonged fight that preceded it. How many Americans could withstand a similar five-year court battle to vindicate their right to petition the government?

Diana, Nicole, and Ron are part of a growing number of Americans who have been punished for speaking their minds about issues and government. To secure their most fundamental First Amendment rights, they have been forced to wage costly, years-long legal battles that most Americans could never afford. The Institute for Free Speech cannot take every case. For every person who stands and fights, countless more are discouraged from speaking by an ever-increasing array of state laws and regulations governing all manner of political speech.

The Institute for Free Speech is publishing this Index for Diana and Nicole and Ron and every other American who speaks about their government. They do so because they are passionate about their values and their communities. They cherish their freedom to speak as an essential liberty protected by the Constitution, and they exercise it with patriotic duty to try to improve our society. Yet very few know the full extent to which states now regulate and suppress speech about government. This Index casts a light on the shadowy web of state laws that threaten these upstanding citizens and suppress dissent. It de- tails the complicated regulatory mechanisms states have built over decades to quietly achieve what the Constitution expressly forbids – government control over speech.

For citizens, trying to speak and stay on the right side of the law today is “confusing and dispiriting,” often by design. Complex regulations impede independent scholars, small groups of advocates, and passionate citizens from making a difference with their speech. The only voices who can speak effectively are those already in power – the professionalized political actors with the resources necessary to operate in an increasingly legalistic and bureaucratic environment. Typically, that means having an army of high-priced lawyers at your side to help navigate such complicated laws.

Since 2005, the Institute for Free Speech has been fighting to roll back the overregulation of political speech that has effectively silenced most citizens in our democracy. We provide pro bono representation to Americans like Diana, Nicole, and Ron. And we try to help people understand the laws that make it so hazardous to participate in American politics today.

But in the vast majority of states, very few people understand the harmful speech impacts of these laws and rules. To the extent they are known at all, citizens and lawmakers often view these laws as nothing more than campaign finance regulations – rules supposedly intended to keep politics free of corruption, not restrict the First Amendment. In each state, only a handful of experts and attorneys know the truth – that the primary effect, and often the primary purpose, of these laws is to restrict speech.

The Index reflects a key part of the Institute’s mission. It aims to bring knowledge of these laws and their effects to anyone with the curiosity to learn. In the process, it exposes these state laws for what they really are: restrictions on the First Amendment. To produce this Index, the Institute undertook a comprehensive effort to decipher the legal mumbo-jumbo, examine how these laws actually work, and figure out which states allow citizens to speak freely and openly about their government – and which states do not.

Why do so many states disregard the speech-chilling impact of their laws? For some, it is ignorance; for others, a failure to recognize who is threatened by the laws; and for a contemptible few, it is a desire to silence their critics.

The Free Speech Index shines a light on the states so that everyone can see how their laws harm First Amendment rights. Hopefully, it also shows a path forward. Armed with this knowledge, the people can work to fix their laws and ensure that every American is truly free to speak.

To read the complete Index, including a detailed description of each category, click here.