Introduction

As the 2022 midterm elections approach, we’ll no doubt see media pundits aiming to predict who will win based on how much money each candidate has behind them. Proponents of intense regulation on campaign spending have long touted a supposedly causal effect between money and electoral success as justification. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the higher-spending candidate won 87.71% of the U.S. House races in 2020.1 On its face, this appears to support the notion that money determines who earns political office. But figures like these tend to obfuscate more than inform about the role of money in campaigns.

Often, campaign contributions reflect a candidate’s attractiveness to voters; they don’t represent the cause of that attraction. Other factors, like name-recognition from celebrity or incumbency, play a stronger role in both electoral success and campaign giving.2

To study around factors like these that confuse the results, this report narrows to a subset of 2020 House primary races that provide for a cleaner analysis of money’s role in electoral success. It then examines what went right for the outspent victors – or what went wrong for their better-financed opponents. It is a qualitative deep dive meant to add depth to our understanding of the factors that aid or harm electoral success, of which campaign spending is only one. The four lessons that follow can help improve our understanding of the role of money in politics:

1. It’s not enough to get your message out – voters must like it.

2. The media has tremendous power over how candidates are portrayed to voters.

3. It matters what candidates spend their money on.

4. Incumbents aren’t the only candidates who benefit from name recognition.

Electoral politics is complicated. While races can’t be reduced to the factors examined in this report, they can’t be reduced to spending alone either. To be sure, money is a valuable campaign asset. It allows candidates to speak to voters and helps motivate civic participation. But it isn’t a miracle worker, and it can’t buy elections.

Methodology

In the 2020 election cycle, the average incumbent House member raised over $2.7 million for their campaign, while the average challenger raised a little over $400,000.3 Congressional incumbents won 96% of their races in that election.4 Because incumbents tend to raise more money and usually win their races, some believe that they “buy” their wins. A more likely explanation is that winning and raising more money are both byproducts of name identification and existing political support networks that challengers do not enjoy.

General elections, moreover, nearly always pit two partisan candidates against one another. Most House districts and states tilt strongly to one of the major parties and thus the election will inherently favor one party or the other. A solid Republican district will almost always elect the Republican candidate regardless of that race’s campaign finance dynamic (and a solid Democratic district, the Democrat). But the nominee of the party heavily favored in a race is also likely to raise more money, both because they have more party members to draw donors from and because their opponent’s slim chance of success will dissuade many donors from “wasting” their contributions on a long-shot candidate. This effect distorts the apparent relationship between money and winning.

Further, the report examines only primaries that occur before a general election that either party stands to win. If the general election is likely not competitive, perhaps because the district is solidly Democratic, then the Republican primary (in this example) normally will not draw strong candidates. Some may run simply to gain attention. Others may use the opportunity to gain traction within their party’s organization. The report filters to a subset of 2020 races to eliminate many extraneous factors from the analysis. It discards the effect of incumbency advantages by studying only races without incumbents. It also minimizes distortions created by districts that tilt heavily to one party or another by examining primary elections instead of general elections. If securing the seat is near impossible, minority party candidates might not employ campaign strategies geared towards victory, so citing their finances as a factor in their loss is futile.

Further supporting the exclusion of these noncompetitive districts is the fact that the dominant party’s primary is effectively the general, e.g. the Democratic primary winner in a solid blue district will almost certainly win the general election against any Republican candidate. In such a district, results are likely to vary dramatically from race to race. Majority party candidates could be driven toward hyper-partisanship as a method of standing out from the pack, or they might seek to appear the more moderate and reasonable choice. Candidates could be focused on particular intra-party support institutions that would correlate with different ingrained levels of funding support. Interpreting the expected role of spending on candidates in such races is highly difficult and would likely muddy the results of our analysis.

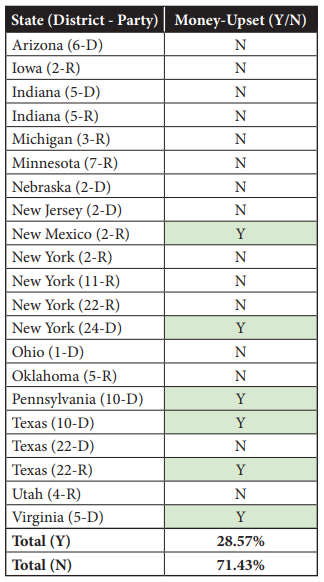

Applying all the filters as described above, the report examines only primary races with no incumbent in a competitive district.5,6 This includes primaries for each party in open seats, where the incumbent is not running for reelection. It also includes primaries to select a challenger to a vulnerable incumbent. These filters yield a pool of 21 races.

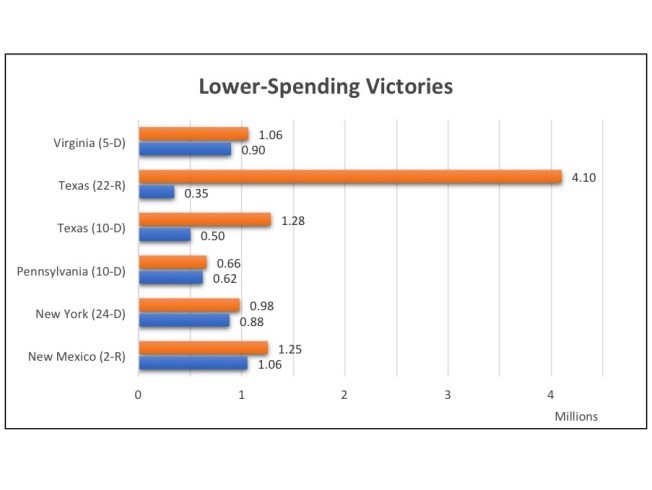

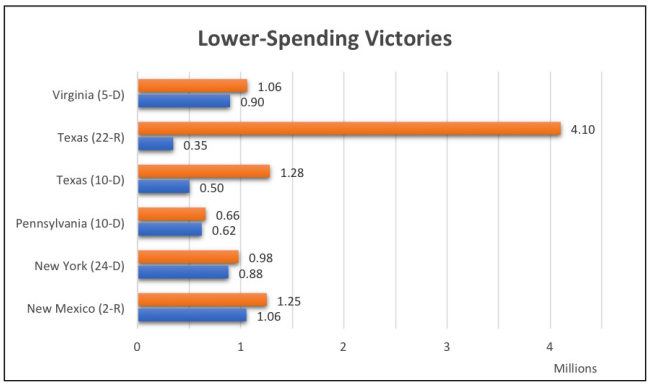

Using our screen for races, we find that candidates who spent less won far more often than they do in all general elections.7 While the lower spending candidate in 2020 House general election races won only 12% of the time, in the primaries studied here, the win rate was close to 30%.

If money buys elections, then one would expect the lower-spending candidates in these races to lose even more often, yet the share of high spenders who lost was more than twice as high as the rate in general elections. This leads one to wonder: what happened in the races where a lower-spending candidate won?

Four Lessons from Outspent Winners in 2020 House Primary Races

(1) Message Matters

Circulating campaign messages does no good when voters don’t like what they’re hearing. In New York’s 24th district, Dana Balter successfully secured the Democratic candidacy with a primary win over her better-financed opponent Francis Conole. In short, it seems Balter had a message and demeanor that better resonated with voters, despite her monetary disadvantage.

When Conole allegedly “mailed out campaign literature full of half-truths and personal attacks,” one reader of The Daily Orange took to Balter’s defense in a guest column.8

The column reads, “She has developed a platform that responds to the urgent needs of this community and did not give up despite the false personal attacks delivered by [incumbent Republican John] Katko in the last election. She will definitely not stand down as Conole uses those same dirty tricks…” The lesson? Not all ad buys woo voters. Sometimes, they only strike a nerve.

It was true for Democrats in New York’s 24th, and it was true for Republicans in Texas’s 22nd. Kathaleen Wall, who spent $4.1 million to Troy Nehls’s $346,000 by the March 3rd primary, had overwhelmingly focused on attack ads.9 Reportedly, she had also moved into the district from Houston just to seek the seat, while Nehls had spent years serving as the local sheriff. Unsurprisingly, a voter survey favored Nehls dramatically – and so did the vote count.

Some voters told Houston’s Fox 26 that Wall’s “irritating onslaught of [attack ads] turned them against the outsider.” One described checking the mail and finding “just a ridiculous amount of negative advertising.” Another voter, who had known Nehls for more than two decades, said that “there is a lot of money involved with [Wall], but Troy is going to make it. He’s the right person.” Fox 26 reported that between two different early voting facilities, none of the dozens surveyed signaled support for Wall.10

While this covers only a sample of the voter attitudes and news coverage, it reflects the final vote counts in these races. It’s important to remember that spending more money doesn’t secure victory, but turning off voters secures defeat.

(2) The Media Plays a Critical Role

Candidates choose what to tell you about their personal and professional histories. It’s natural to look elsewhere for more of the picture, but beware: candidates aren’t the only selective storytellers.

Shannon Hutcheson, the highest spending candidate in the Democratic primary for Texas’s 10th district, lost the Democratic primary to two opponents, Mike Siegel and Pritesh Gandhi (Siegel eventually won a runoff). Hutcheson had highlighted her legal work for Planned Parenthood during her campaign, but the media portrayed this work as an anomaly on an otherwise less-valorous résumé for a Democrat.

The Texas Observer ran a headline in November of 2019 reading, “Texas Congressional Candidate Shannon Hutcheson Defended Corporations Against the Vulnerable. EMILY’s List Endorsed Her Anyway.”11

From the Observer story, we learn that Hutcheson “voted in the 2010 GOP primary,” “made several campaign contributions to conservative judges,” and “defended a litany of businesses against claims of wrongdoing…” These allegations were toxic to Democratic primary voters. Hutcheson did not agree to an interview with the Observer, but the story quoted the following statement from her campaign: “As the co-founder of a women-owned law firm, my goal is fair outcomes for everyone. My job is to ensure employers are complying with laws to create an equitable workplace for employees.”

Another story from The Texas Tribune showed that her opponents quickly joined in on the attacks. It quotes Gandhi, a physician, saying “Every day I walk into a not-for-profit health clinic, and we serve 18,000 uninsured or under-insured Central Texans… We need to put folks forward that have a long track record of representing our progressive values…”12 In the same story, Hutcheson tried to defend her legal career: “I’ve been a lawyer for 23 years, worked on hundreds and hundreds of matters, and the idea that you can cherry-pick two or three and build a narrative around that — I wholesale reject that.”

But the media ran with that narrative. The local newspapers were also endorsing her opponents. The Austin American-Statesman endorsed Gandhi in an editorial.13 The Austin Chronicle and The Houston Chronicle did the same for Siegel. Hutcheson was not endorsed by any major paper with readers in the district. Of course, everyone will have their favorite candidates, even newspaper editors. But newspaper endorsements can influence voters’ perception of the candidates.

While there’s more to success than media approval, Hutcheson’s spending could only go so far. Having favorable news stories and editorials endorsing your candidacy is valuable and can tilt a race.

(3) It Matters What You Spend Your Money On

Not all campaign expenditures go toward speech. Money is also spent on staff salary, for political strategists, at restaurants, and on myriad other things that seemingly would not affect voter attitudes directly. The campaign dollars that matter to voters are those spent on things like advertising, rallies, printing, canvassing, and the like.

In the Democratic primary for Virginia’s 5th district, winner Cameron Webb was not the highest spender, but he did spend the most on speech. Opponent Roger Dean Huffstetler had spent the most by the primary at just over $1 million. Just behind was Webb, with a little under $900,000. Huffstetler, however, had directed an estimated $351,685 of his expenditures to speech-related categories. Webb had spent $471,829 on such categories.14

Spending the most is not beneficial in itself – there are more ways to waste money than to put it to proper use. But spending on campaign speech is important, especially when the messages are aimed at scoring voters. In this race, spending the most mattered less than getting the message out.

(4) Name Recognition and Endorsements Are Important Factors

Another important lesson we can glean from these lower-spending 2020 House primary winners is that name-recognition can be more powerful than spending.

Consider Yvette Herrell’s primary victory over the higher-spending Claire Chase in New Mexico’s 2nd district. Herrell had a long political track record as a former state representative. It was also not her first bid for the seat, as she was the district’s Republican primary winner in 2018. This likely helped gain her many endorsements, which included U.S. Rep. Jim Jordan and former Gov. Mike Huckabee.15 Familiarity to voters and endorsements by highly visible party figures are assets to any candidate.

In Pennsylvania’s 10th district, the Democratic primary yielded another win by a lower-spending candidate. Eugene DePasquale spent less money than his opponent, political neophyte Tom Brier. But unlike Brier, his name was not a new one to voters or party leaders.

DePasquale was a former state representative and had been the Pennsylvania auditor general for 8 years, an elected position. Perhaps for this reason, he enjoyed numerous endorsements from Democratic officials.16 His name-recognition advantage may also have been aided by the pandemic. With in-person campaigning out of the question and COVID-19 commanding headlines, wrote Charles Thompson for PennLive, “it hurt Brier’s efforts to cut into his name identification advantage.”17

Whether the outcome would have been different in a normal election cycle, we will never know. But we can say for certain that it wasn’t an excess of campaign cash that landed Herrell and DePasquale their party’s nominations. Quite possibly, it was their names.

Conclusion

That the higher spender usually wins is a gross oversimplification of what it takes to run a successful campaign.

Some conditions make it very likely that a candidate will win regardless of spending. Incumbency is one example, with name-recognition and existing public support leading to higher success rates. Partisanship and non-competitive districts also make fundraising and winning easier. A Republican nominee in most of Oklahoma won’t struggle to find support against a Democratic opponent. They’re likely to raise and spend more, and they’re likely to earn more votes from the state’s heavily Republican voter base. But again, the money doesn’t create the votes.

This study eliminated factors like these that cloud the results and examined the question, “In races where money has a strong potential to make the difference, what led to the success of so many lower-spending candidates?”

In some cases, the highest spender’s message wasn’t right. In others, spending the most couldn’t beat having a recognizable name. The media also won’t necessarily favor the candidate with the biggest campaign war chest, and that can make all the difference in a close race. And sometimes the lower spender spends more on speech and less on overhead.

Spending money will always be one piece of the puzzle, of course. Yard signs, mailers, advertisements, and other communication mediums cost money. If a candidate wants to inform and win voters, they will need to buy exposure. But spending more doesn’t make a candidate win.

In the end, only one thing wins elections and that’s earning the most votes. The lessons we learn from this subset of 2020 House primaries demonstrate that while money can help make you a known candidate, it can’t make you a winning one. As we approach the 2022 midterms, and inevitably see the media exploit election spending for cheap headlines, we’ll know what those figures actually teach us – and what they don’t.

Footnotes

1 “Did Money Win?” Center for Responsive Politics. Available at: https://www.opensecrets.org/elections-overview/winning-vs-spending?cycle=2020.

2 Cindy D. Kam and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. “Name Recognition and Candidate Support.” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 57:4. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23496668. (Oct. 2013) at 971-986.

3 “Incumbent Advantage,” Center for Responsive Politics. Available at: https://www.opensecrets.org/elections-overview/incumbent-advantage.

4 “Election results, 2020: Incumbent win rates by state,” Ballotpedia. Available at: https://ballotpedia.org/Election_results,_2020:_Incumbent_win_rates_by_state (February 11, 2021).

5 We disregard primary races where only one candidate’s campaign is financially viable. Races where the second highest spender was more than 25 times outspent are excluded for lack of competition.

6 For “competitive primaries,” this study uses primaries in districts rated “Toss Up” by The Cook Political Report. Because competitive primaries occur before competitive general elections, we utilize the race ratings closest to the general election. “2020 House Race Ratings,” The Cook Political Report. Available at: https://www.cookpolitical.com/ratings/house-race-ratings/230686 (November 2, 2020).

7 Spending data was collected from https://www.fec.gov/. The report considers spending from January 1, 2019 through the date of the respective primary.

8 Patty Familo, “Francis Conole uses falsehoods to attack primary opponent Dana Balter,” The Daily Orange. Available at: http://ftp.dailyorange.com/2020/05/francis-conole-uses-falsehoods-attack-primary-opponent-dana-balter/ (May 21, 2020).

9 Greg Googan, “Voters dislike negative onslaught in District 22 run-off election,” Fox 26 Houston. Available at: https://www.fox26houston.com/news/voters-dislike-negative-onslaught-in-district-22-run-off-election (July 9, 2020).

10 Id.

11 Justin Miller, “Texas Congressional Candidate Shannon Hutcheson Defended Corporations Against the Vulnerable. EMILY’s List Endorsed Her Anyway.” Texas Observer. Available at: https://www.texasobserver.org/texas-congressional-candidate-shannon-hutcheson-defended-corporations-against-the-vulnerable-emilys-list-endorsed-her-anyway/ (November 18, 2019).

12 Patrick Svitek, “Congressional candidate’s legal work attracts scrutiny in battleground Democratic primary,” The Texas Tribune. Available at: https://www.texastribune.org/2019/12/21/shannon-hutchesons-legal-work-attracts-scrutiny-congressional-race/ (December 21, 2019).

13 “Texas’ 10th Congressional District election, 2020 (March 3 Democratic primary),” Ballotpedia. Available at: https://ballotpedia.org/Texas’_10th_Congressional_District_election,_2020_(March_3_Democratic_primary).

14 “Speech-related categories” include any disbursements that could create, distribute, or aid in the creation or distribution of campaign messages. Any disbursement with a label containing the words “campaign materials,” “advertisement,” “printing,” “mail,” and “website design,” to name a few, are considered a speech-related category of disbursement for this study. A full list of the words and phrases deemed to signal a speech-related disbursement is available upon request.

15 “New Mexico’s 2nd Congressional District election, 2020 (June 2 Republican primary),” Ballotpedia. Available at: https://ballotpedia.org/New_Mexico%27s_2nd_Congressional_District_election,_2020_(June_2_Republican_primary)#Satellite_spending.

16 Charles Thompson, “Tom Brier, Eugene DePasquale vie for Democrats’ big shot in 10th Congressional District in Pa.,” PennLive. Available at: https://www.pennlive.com/news/2020/05/tom-brier-eugene-depasquale-vie-for-democrats-big-shot-in-pennsylvanias-10th-congressional-district-winner-gets-us-rep-scott-perry-in-the-fall.html (May 28, 2020).

17 Id.